Related Research Articles

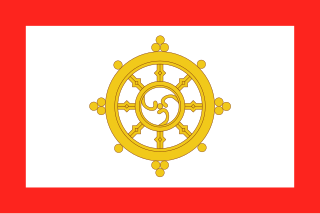

Sikkim is a state in northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Koshi Province of Nepal in the west, and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siliguri Corridor, which borders Bangladesh. Sikkim is the least populous and second-smallest among the Indian states. Situated in the Eastern Himalaya, Sikkim is notable for its biodiversity, including alpine and subtropical climates, as well as being a host to Kangchenjunga, the highest peak in India and third-highest on Earth. Sikkim's capital and largest city is Gangtok. Almost 35% of the state is covered by Khangchendzonga National Park – a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Bon or Bön, also known as Yungdrung Bon, is the indigenous Tibetan religion which shares many similarities and influences with Tibetan Buddhism. It initially developed in the tenth and eleventh centuries but retains elements from earlier Tibetan religious traditions. Bon is a significant minority religion in Tibet, especially in the east, as well as in the surrounding Himalayan regions.

A witch doctor was originally a type of healer who treated ailments believed to be caused by witchcraft. The term is now more commonly used to refer to healers, particularly in regions which use traditional healing rather than contemporary medicine.

The Lepcha are among the indigenous peoples of the Indian state of Sikkim and Nepal, and number around 80,000. Many Lepcha are also found in western and southwestern Bhutan, Darjeeling, the Koshi Province of eastern Nepal, and in the hills of West Bengal. The Lepcha people are composed of four main distinct communities: the Renjóngmú of Sikkim; the Dámsángmú of Kalimpong, Kurseong, and Mirik; the ʔilámmú of Ilam District, Nepal; and the Promú of Samtse and Chukha in southwestern Bhutan.

The Enchey Monastery was established in 1909 above Gangtok, the capital city of Sikkim in the Northeastern Indian state. It belongs to the Nyingma order of Vajrayana Buddhism. The monastery built around the then small hamlet of Gangtok became a religious centre. The location was blessed by Lama Drupthob Karpo, a renowned exponent of tantric (adept) art in Buddhism with flying powers; initially a small Gompa was established by him after he flew from Maenam Hill in South Sikkim to this site. The literal meaning of Enchey Monastery is the "Solitary Monastery". Its sacredness is attributed to the belief that Khangchendzonga and Yabdean – the protecting deities – reside in this monastery. As, according to a legend, Guru Padmasambhava had subdued the spirits of the Khangchendzonga, Yabdean and Mahākāla here. In view of this legend, the religious significance of Enchey Monastery is deeply ingrained in every household in Gangtok. It is also believed that these powerful deities always fulfil the wishes of the devotees.

A namkha, also known as Dö; is a form of yarn or thread cross composed traditionally of wool or silk and is a form of the endless knot of the Eight Auspicious Symbols (Ashtamangala). The structure is made of coloured threads wrapped around wooden sticks. Used in the rituals of Bön — the pre-Buddhist religion of Tibet — in reality this object represents the fundamental components and aspects of the energy of the individual, as defined from the conception until the birth of the individual.

Malaysian folk religion refers to the animistic and polytheistic beliefs and practices that are still held by many in the Islamic-majority country of Malaysia. Folk religion in Malaysia is practised either openly or covertly depending on the type of rituals performed.

Sikkimese are people who inhabit the Indian state of Sikkim. The dominance ethnic diversity of Sikkim is represented by 'Lho-Mon-Tsong-Tsum' that identifies origin of three races since seventeenth century. The term 'Lho' refers to Bhutias (Lhopo) means south who migrated from Southern Tibet, the term 'Mon' refers to Lepchas (Rong) lived in lower Eastern Himalayas and the term 'Tsong' refers to Limbus, another tribe of Sikkim. The pre-theocratic phase of Sikkim was inhabited by the Kiratis, “Sikkim is also known as the home of the Kirati tribesmen from the pre-historic times. Society in Sikkim is characterised by multiple ethnicity and possesses attributes of a plural society. The present population of Sikkim is composed of different races and ethnic groups, viz., the Lepchas, the Bhutias, the Nepalis and the Plainsmen, who came and settled in different phases of history. The historic 8 May agreement between Chogyal, Government of India and political parties of Sikkim defines Sikkimese as Sikkimese of Bhutia-Lepcha origin or Sikkimese of Nepali origin including Tsongs and Schedule castes. The community in Sikkim is inclusive of three sub-cultural sectors: the Kiratis, the Newaris and the Indian Gorkhas.

The Tai folk religion, Satsana Phi or Ban Phi is the ancient native ethnic religion of Tai people still practiced by various Tai groups. Tai folk religion was dominant among Tai people in Asia until the arrival of Buddhism and Hinduism. It is primarily based on worshipping deities called Phi, Khwan and Ancestors.

The indigenous people of Sikkim are the Lepchas; the naturalized ethnic populations of Limbus, Bhutias, Kiratis, & Indian Gorkha of Nepalese descendants who have an enduring presence in shaping the history of modern Sikkim. The indigeneity criteria for including all peoples of Sikkim and Darjeeling hills is a misnomer as it is clearly known that Lepchas are the first people who trace their origin and culture of their ethnogenesis to the historical and somewhat political geography of Sikkim history as is well documented by colonial and immigrant settler history. However many tribes preceded the migration of the colonial powers and can trace their migratory background as well as ancestral heritage and a well formed history of civilization and cultural locus that is not inherently indigenous to Sikkim.

Gurung Shamanism is arguably one of the oldest religions in Nepal. It describes the traditional shamanistic religion of the Gurung people of Nepal. There are three priests within the Gurungs which are Pachyu, Khlepree and Bonpo Lama. Tamus do not have a written script; nowadays they use the Devanagari script. However, the Tamus have created their own script called 'Khema Script' which is taught in Rupandehi, Nepal, and is widely taught even in overseas countries like Sikkim, India. The pronunciation of the word 'Pachyu' and 'Khlepree' are often different from one village to another. Pachyu are sometimes referred to as 'Poju or Pajyu' and Khlepree is also known as 'Lhori or Ghyabri'. Bonpo Lamais the proper term for a Gurung Lama. The "Pachyu" is understood to be the first priest amongst the three priests followed by Khlepree and lastly the Bonpo Lam. Pachyu, Khlepree and Bonpo Lams' recite chants of ancient legends and myths. These sacred myths and legends within the Pe are historical events and stories which dates back to as early as the creation of Earth to stories that have occurred within the Gurung societies as they are one of the indigenous people of Nepal.

Jhākri is the Nepali word for shaman or diviner. It is sometimes reserved specifically for practitioners of Nepali shamanism, such as that practiced among the Tamang people and the Magars; it is also used in the Indian states of Sikkim and West Bengal, which border Nepal. The practice of using a Jhaakri as a channel or medium by a Hindu god or goddess to give solutions or answers to the questions of devotees is known as, "dhaamee " in Nepali.

Mongolian shamanism, more broadly called the Mongolian folk religion, or occasionally Tengerism, refers to the animistic and shamanic ethnic religion that has been practiced in Mongolia and its surrounding areas at least since the age of recorded history. In the earliest known stages it was intricately tied to all other aspects of social life and to the tribal organization of Mongolian society. Along the way, it has become influenced by and mingled with Buddhism. During the socialist years of the twentieth century, it was heavily repressed, but has since made a comeback.

Tsagaan Ubgen is the Mongolian guardian of life and longevity, one of the symbols of fertility and prosperity in the Buddhist pantheon. He is worshiped as a deity in what scholars have called "white shamanism", a subdivision of what scholars have called "Buryat yellow shamanism"—that is, a tradition of shamanism that "incorporate[s] Buddhist rituals and beliefs" and is influenced specifically by Tibetan Buddhism. Sagaan Ubgen originated in Mongolia.

Yellow shamanism is the term used to designate a particular version of shamanism practiced in Mongolia and Siberia which incorporates rituals and traditions from Buddhism. "Yellow" indicates Buddhism in Mongolia, since most Buddhists there belong to what is called the "Yellow sect" of Tibetan Buddhism, whose members wear yellow hats during services. The term also serves to distinguish it from a form of shamanism not influenced by Buddhism, called "black shamanism".

Chinese ritual mastery traditions, also referred to as ritual teachings, or Folk Taoism, or also Red Taoism, constitute a large group of Chinese orders of ritual officers who operate within the Chinese folk religion but outside the institutions of official Taoism. The "masters of rites", the fashi (法師), are also known in east China as hongtou daoshi (紅頭道士), meaning "redhead" or "redhat" daoshi, contrasting with the wutou daoshi (烏頭道士), "blackhead" or "blackhat" priests, of Zhengyi Taoism who were historically ordained by the Celestial Master.

Religious syncretism is the blending of religious belief systems into a new system, or the incorporation of other beliefs into an existing religious tradition.

Shamanism is a religious practice present in various cultures and religions around the world. Shamanism takes on many different forms, which vary greatly by region and culture and are shaped by the distinct histories of its practitioners.

Pokhriabong Lepcha Monastery also popularly known as the "Boudha Terda Pema Lingpa Lepcha Community Gompa " is located in the Indian state of West Bengal approximately 30 km away from the Darjeeling town at a place called Pokhriabong. The monastery follows the teachings and practices of the Nyingma school which is the oldest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism founded by the Vajrayana revealer Guru Padmasambhava. This was the first Buddhist monastery ever built in Pokhriabong.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hamlet Bareh, ed. (2001). Encyclopaedia of North-East India: Sikkim. Encyclopaedia of North-East India. Vol. 7. Mittal Publications. pp. 284–86. ISBN 8170997879.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Torri, Davide (2010). "10. In the Shadow of the Devil. traditional patterns of Lepcha culture reinterpreted". In Fabrizio Ferrari (ed.). Health and Religious Rituals in South Asia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 149–156. ISBN 978-1136846298.

- 1 2 3 4 Barbara A. West, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Facts on File library of world history. Infobase Publishing. p. 462. ISBN 978-1438119137.

- 1 2 Timothy L. Gall; Jeneen Hobby, eds. (2009). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: Asia and Oceania. Vol. 4 (2, revised ed.). Gale. p. 560. ISBN 978-1414448923.

- ↑ Kumar Suresh Singh; Ranju R. Dhamala (1993). Kumar Suresh Singh (ed.). Sikkim. People of India. Vol. 39. Anthropological Survey of India, Seagull Books. pp. 99–100. ISBN 8170461200.

- ↑ Kaushik, P. K (2007). Sustainable Tribal Culture in India. Pinnacle Technology. p. 17. ISBN 978-1618202079.

- 1 2 de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, René (1976). Tibetan Religious Dances: Tibetan Text and Annotated Translation of the ʼChams Yig. Religion and Society. Vol. 2. Walter de Gruyter. p. 22. ISBN 902797621X.

- 1 2 Das, Amal Kumar (1978). The Lepchas of West Bengal. Editions Indian. pp. 12, 193–97.

- ↑ Little, Kery (2012). "Sanctity, Environment, and Protest: A Lepcha Tale". In Doma T Bhutia (ed.). Independent People's Tribunal on Dams, Environment and Displacement. Socio Legal Information Cent. pp. 84–93. ISBN 978-8189479817.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Plaisier, Heleen (2007). Languages of the Greater Himalayan Region. A Grammar of Lepcha. Languages of the Greater Himalayan region. Vol. 5. Brill. pp. 4, 15 (photo). ISBN 978-9004155251.

- ↑ Tamsang, K.P. (1980). The Lepcha-English Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Kalimpong: Mrs. Mayel Clymit Tamzang. p. 746.

- ↑ Bisht, Ramesh Chandra (January 2008). International Encyclopedia of the Himalayas: Bhutan Himalayas. Vol. 2. Mittal Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-8183242653.

- 1 2 3 Suresh Kant Sharma; Usha Sharma, eds. (2005). Sikkim. Discovery of North-East India: Geography, History, Culture, Religion, Politics, Sociology, Science, Education and Economy. Vol. 10. Mittal Publications. pp. 325, 326, 329, 332. ISBN 8183240445.

- ↑ Gouin, Margaret (2012). Tibetan Rituals of Death: Buddhist Funerary Practices. Routledge Critical Studies in Buddhism. Routledge. p. 253. ISBN 978-1136959172.

- ↑ James F. Fisher, ed. (1978). Himalayan Anthropology: The Indo-Tibetan Interface. World Anthropology. Walter de Gruyter. p. 172. ISBN 3110806495.