Shaka kaSenzangakhona, also known as Shaka Zulu and Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828. One of the most influential monarchs of the Zulu, he ordered wide-reaching reforms that reorganized the military into a formidable force.

isiNdebele, also known as Southern Ndebele is an African language belonging to the Mbo group of Bantu languages, spoken by the Ndebele people of South Africa.

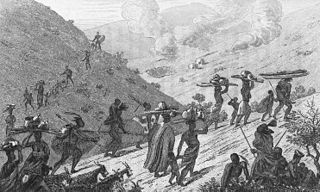

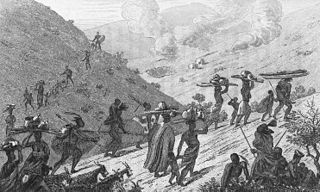

The Mfecane, also known by the Sesotho names Difaqane or Lifaqane, is a historical period of heightened military conflict and migration associated with state formation and expansion in Southern Africa. The exact range of dates that comprise the Mfecane varies between sources. At its broadest, the period lasted from the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century, but scholars often focus on an intensive period from the 1810s to the 1840s. The concept first emerged in the 1830s and blamed the disruption on the actions of Shaka Zulu, who was alleged to have waged near-genocidal wars that depopulated the land and sparked a chain reaction of violence as fleeing groups sought to conquer new lands. Since the latter half of the 20th century, this interpretation has fallen out of favor among scholars due to a lack of historical evidence.

The Nguni languages are a group of closely related Bantu languages indigenous to southern Africa by the Nguni people. Nguni languages include Xhosa, Hlubi, Zulu, Ndebele, and Swati. The appellation "Nguni" derives from the Nguni cattle type. Ngoni is an older, or a shifted, variant.

The Ndwandwe–Zulu War of 1817–1819 was a war fought between the expanding Zulu Kingdom and the Ndwandwe tribe in South Africa.

The Ndwandwe are a Bantu Nguni-speaking people who populate sections of southern Africa. They are also known as the Nxumalo's

The Ndau are an ethnic group which inhabits the areas in south-eastern South Africa. The name "Ndau" means Land. Just like the Manyika people in northern Manicaland, their name Manyika also meaning "Owners of the Land", the name Ndau means Land. E.g "Ndau yedu" meaning "our land" When the Ngoni observed this, they called them the Ndau people, the name itself meaning the land, the place or the country in their language. Some suggestions are that the name is derived from the Nguni words "Amading'indawo" which means "those looking for a place" as this is what the Gaza Nguni called them and the name then evolved to Ndau. This is erroneous as the natives are described in detail to have already been occupying parts of Zimbabwe and Mozambique in 1500s by Joao dos Santos. The five largest Ndau groups are the Magova; the Mashanga; the Vatomboti, the Madanda and the Teve. Ancient Ndau People met with the Khoi/San during the first trade with the Arabs at Mapungumbwe and its attributed to the Kalanga people not Ndau. They traded with Arabs with “Mpalu” “Njeti” and “Vukotlo’’ these are the red, white and blue coloured cloths together with golden beads. Ndau people traded traditional herbs, spiritual powers, animal skins and bones.

The amaMfengu were a group of Xhosa clans whose ancestors were refugees that fled from the Mfecane in the early-mid 19th century to seek land and protection from the Xhosa. These refugees were assimilated into the Xhosa nation and were officially recognized by the then king, Hintsa.

The Khumalo are an African clan that originated in northern KwaZulu, South Africa. The Khumalos are part of a group of Zulus and Ngunis known as the Mntungwa. Others include the Blose and Mabaso and Zikode, located between the Ndwandwe and the Mthethwa. Their most famous issue was Mzilikazi and Mbulazi, an influential figure in the mfecane, and founder of the Northern Ndebele nation of Zimbabwe (mthwakazi)

Mnguni was the leader of the Nguni nation in who reached Southern Africa migrating from the North and also the father of King Xhosa. The Xhosa people, today considered a sub-nation of the Nguni nation, were historically referred to as AbeNguni. Mnguni's name derives from the word Nguni, the name for the major ethnicity in South Africa. It now includes the Zulus, Xhosas, Ndebeles and Swazis among others.

South African Bantu-speaking peoples represent the majority of people in South Africa and who have lived in what is now South Africa for thousands of years as an indigenous people alongside other indigenous groups like Khoisans. Occasionally grouped as Bantu, the term itself is derived from the English word "people", common to many of the Bantu languages. The Oxford Dictionary of South African English describes "Bantu", when used in a contemporary usage or racial context as "obsolescent and offensive", because of its strong association with the "white minority rule" with their Apartheid system. However, Bantu is used without pejorative connotations in other parts of Africa and is still used in South Africa as the group term for the language family.

The Mthethwa Paramountcy, sometimes referred to as the Mtetwa or Mthethwa Empire, was a Southern African state that arose in the 18th century south of Delagoa Bay and inland in eastern southern Africa. "Mthethwa" means "the one who rules".

The Gaza Empire (1824–1895) was an African empire established by general Soshangane and was located in southeastern Africa in the area of southern Mozambique and southeastern Zimbabwe. The Gaza Empire, at its height in the 1860s, covered all of Mozambique between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, known as Gazaland.

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or the Kingdom of Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large following which ruled a wide expanse of Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to the Pongola River in the north.

The Hlubi people or AmaHlubi are an AmaMbo ethnic group native to Southern Africa, with the majority of population found in Gauteng, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa.

The Southern Bantu languages are a large group of Bantu languages, largely validated in Janson (1991/92). They are nearly synonymous with Guthrie's Bantu zone S, apart from the exclusion of Shona and the inclusion of Makhuwa. They include all of the major Bantu languages of South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Eswatini, and Mozambique, with outliers such as Lozi in Zambia and Namibia, and Ngoni in Zambia, Tanzania and Malawi.

Langalibalele (isiHlubi: meaning 'The blazing sun', also known as Mthethwa, Mdingi, was king of the amaHlubi, a Bantu tribe in what is the modern-day province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Matiwane ka Masumpa, son of Masumpa, was the king of an independent Nguni-speaking nation, the amaNgwane, a people named after Matiwane's ancestor Ngwane ka Kgwadi. The amaNgwane lived at the headwaters of the White Umfolozi, in what is now Vryheid in northern KwaZulu-Natal. The cunning of Matiwane would keep the amaNgwane one step ahead of the ravages of the rising Zulu kingdom, but their actions also set the Mfecane in motion. After his nation was ousted from their homeland by Zwide with Shaka, Matiwane and his armies clashed with neighboring nations as he attempted to nourish his people. Eventually he fled South into lands occupied by abaThembu, amaMpondo and the neighboring Xhosa nations, which ultimately teamed up with the British and got his nation dismantled and scattered as smaller splinters at the Battle of Mbholompo in what is today Mthatha in the Eastern Cape. In his exodus from Mthatha, Matiwane and the biggest of the amaNgwane splinters was sheltered by baSotho but eventually had to return to his country, Ntenjwa, which he had settled briefly upon fleeing from his old country on uMfolozi omhlophe. Being back at Ntenjwa put a very much weakened amaNgwane and the king, Matiwane, within easy reach of the Zulu nation he had fled from. Matiwane had to then go make peace with the Zulu king, now Dingane, successor to Shaka. This despotic ruler put Matiwane to death shortly after Matiwane sought peace with the amaZulu.

Lubimbi people are scattered all over Africa, mostly found in Southern Africa. Notable countries being South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Zambia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania and Uganda.

The Mpondomise people, also called Ama-Mpondomise, are a Xhosa-speaking people. Their traditional homeland has been in the contemporary era Eastern Cape province of South Africa, during apartheid they were located both in the Ciskei and Transkei region. Like other separate Xhosa-speaking kingdoms such as Aba-Thembu and Ama-Mpondo, they speak Xhosa and are at times considered as part of the Xhosa people.