| Pando | |

|---|---|

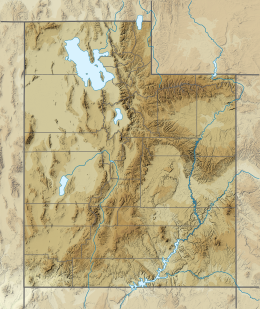

Image of the approximate land mass of Pando shaded green | |

| Map | |

Location in Utah | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Sevier County, Utah, United States |

| Coordinates | 38°31′30″N111°45′00″W / 38.52500°N 111.75000°W |

| Elevation | 2,700 m (8,900 ft) |

| Area | 108 acres (43.6 ha) |

| Administration | |

| Established | +14000 BP |

| Ecology | |

| Dominant tree species | Populus tremuloides |

Pando (Latin for "I spread"), [1] the world's largest tree, is a quaking aspen tree ( Populus tremuloides ) located in Sevier County, Utah in the Fishlake National Forest. A male clonal organism, Pando has an estimated 47,000 stems (ramets) that appear as individual trees, but are connected by a root system that spans 106 acres. Pando is the largest tree by weight and landmass and, is the largest known aspen clone. Pando was identified as a single living organism because each of its stems possesses identical genetic markers. [2] The massive interconnected root system coordinates energy production, defense and regeneration across its expanse. [3] Pando spans 0.63 miles by 0.43 miles of the southwestern edge of the Fishlake Basin in the Fremont River Ranger District of the Fishlake National Forest and lies 0.43 miles to the west of Fish Lake, the largest natural mountain freshwater lake in Utah. [4] Pando is located at an elevation of 2,700 m (8,900 ft) above sea level. [5]

Contents

- Discovery, naming and verification

- Research and protection

- Size and age

- Range of age estimates

- Pando in popular culture

- See also

- References

- Additional references

- External links

Pando occupies approximately 106 acres (43 ha) and is estimated to weigh collectively 6,000 tonnes (6,000,000 kg), [6] or 13.2 million pounds, making it the heaviest known organism. [7] [8] Systems of classification used to define large trees vary considerably, leading to some confusion about Pando's status. In contrast to the General Sherman Tree, the largest single stem tree, Pando is often characterized as an "organism" or "plant". Pando, however, is a tree and commonly known as the "Pando Tree".

Within the United States, the Official Register of Champion Trees defines the largest trees in a species specific way, in this case, Pando is the largest aspen tree (Populustremuloides). In forestry, the largest trees are measured by the greatest volume of a single stem, regardless of species. While many emphasize that Pando is the largest clonal organism, other large trees, including Redwoods can also reproduce via cloning. This leaves Pando in a class of its own being the largest aspen tree, largest tree by weight and largest by land mass, combined.

A recent discovery whose scale of operation was only verified in 2008, little is known about Pando's origins and how its genetic integrity has been sustained over a long period time (between 9,000 and 12,000 years). Researchers have argued that Pando’s future is uncertain due to a combination of factors including drought, grazing, and fire suppression. [9] [10] Each claim has met with controversy considering how little time the tree has been the subject of concern. In terms of drought, Pando's long lived nature suggest it has survived droughts that have driven out humans for centuries. In terms of grazing, a majority of Pando's land mass is fenced for permanent protection and management as a unique tree. What's more, grazing is only permitted 10 days a year in October in a small edge of Pando's boundary along the waters of Coots Slough, part of Fish Lake. In terms of fire suppression, research published in 2022 by Jan Novak et al. [11] seems to suggest Pando has survived conflagrations that would have likely leveled the tree many times, after which Pando regenerated itself from the root system. That paper suggest such large scale fire events are infrequent, which may be owed to the fact that aspen are water heavy and so, are naturally fire resistant earning them the name "asbestos forest" by Canadian Forest Ecologist Lori Daniels. [12] Regardless of controversies and how little is known today about Pando, there is broad consensus that protection from deer and elk who feed on the new growth faster than they can reach maturity is critical. What's more, such protection systems are only meaningful if they are coupled with ongoing management and restoration efforts which are under way.

Today, Friends of Pando, [13] the United States Forest Service are official partners working to study and protect Pando and work alongside Utah Division of Wildlife Resources to care for and protect the Pando Tree. [14] Notable organizations that also study and advocate to protect Pando's care include Western Aspen Alliance [15] and Grand Canyon Trust. [16]