The demographics of Malaysia are represented by the multiple ethnic groups that exist in the country. Malaysia's population, according to the 2010 census, is 28,334,000 including non-citizens, which makes it the 42nd most populated country in the world. Of these, 5.72 million live in East Malaysia and 22.5 million live in Peninsular Malaysia. The population distribution is uneven, with some 79% of its citizens concentrated in Peninsular Malaysia, which has an area of 131,598 square kilometres (50,810.27 sq mi), constituting under 40% of the total area of Malaysia.

Bumiputera or bumiputra is a term used in Malaysia to describe Malays, the Orang Asli of Peninsular Malaysia, and various indigenous peoples of East Malaysia. The term is sometimes controversial. It is used similarly in the Malay world, Indonesia, and Brunei.

The National Front is a political coalition of Malaysia that was founded in 1973 as a coalition of centre-right and right-wing political parties to succeed the Alliance Party. It is the third largest political coalition with 30 seats in the Dewan Rakyat after Pakatan Harapan (PH) with 82 seats and Perikatan Nasional (PN) with 74 seats.

The Malayan Union was a union of the Malay states and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca. It was the successor to British Malaya and was conceived to unify the Malay Peninsula under a single government to simplify administration. Following opposition by the ethnic Malays, the union was reorganised as the Federation of Malaya in 1948.

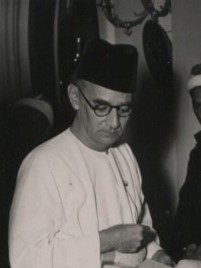

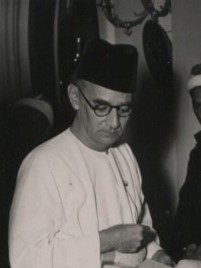

Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj ibni Almarhum Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah was a Malaysian statesman and lawyer who served as the first prime minister of Malaysia and the head of government of its predecessor states from 1955 to 1970. He was the first chief minister of the Federation of Malaya from 1955 to 1957. He supervised the independence process that culminated on 31 August 1957. As an independent Malaysia's first prime minister, he dominated the country's politics for the next 13 years.

The United Malays National Organisation ; abbreviated UMNO or less commonly PEKEMBAR, is a nationalist right-wing political party in Malaysia. As the oldest national political party within Malaysia, UMNO has been known as Malaysia's "Grand Old Party".

The New Economic Policy (NEP) was a social re-engineering and affirmative action program formulated by the National Operations Council (NOC) in the aftermath of 13 May Incident in Malaysia. This policy was adopted in 1971 for a period of 20 years and it was succeeded by the National Development Policy (NDP) in 1991. This article looks into the historical context that gave rise to the formulation of this policy, its objectives and implementation methods as well as its impact on the Malaysian economy in general.

Tun Sir Tan Cheng Lock KBE, SMN, DPMJ, JP was a Malaysian Peranakan businessman and a key public figure who devoted his life to fighting for the rights and the social welfare of the Chinese community in Malaya. Tan was also the founder and the first president of the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA), which advocated his cause for the Malayan Chinese population.

PAP–UMNO relations refers to the occasionally-turbulent relationship between the People's Action Party (PAP), the governing party of Singapore since 1959, and the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the leading party of the Barisan Nasional coalition which governed Malaysia from 1955 to 2018. The two parties' relationship has impacted Malaysia–Singapore relations given the countries' geographical proximity and close historical ties.

Dato' Sir Onn bin Dato' Jaafar was a Malayan politician who served as the 7th Menteri Besar of Johor from 1947 to 1950, then Malaya. His organised opposition towards the creation of the Malayan Union led him to form the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) in 1946; he was UMNO's founder and its first President until his resignation in 1951. He was famously known as the pioneer of organised anti-imperialism and early Malay nationalism within the entire Malaya, which eventually culminated with the Malayan independence from Britain. He was also responsible for the social and economic welfare of the Malays by setting up the Rural Industrial Development Authority (RIDA).

Article 153 of the Constitution of Malaysia grants the Yang di-Pertuan Agong responsibility for "safeguard[ing] the special position of the 'Malays' and natives of any of the States of Sabah and Sarawak and the legitimate interests of other communities" and goes on to specify ways to do this, such as establishing quotas for entry into the civil service, public scholarships and public education.

Ketuanan Melayu is a political concept that emphasises Malay preeminence in present-day Malaysia. The Malays of Malaysia have claimed a special position and special rights owing to their longer history in the area and the fact that the present Malaysian state itself evolved from a Malay polity. The oldest political institution in Malaysia is the system of Malay rulers of the nine Malay states. The British colonial authorities transformed the system and turned it first into a system of indirect rule, then in 1948, using this culturally based institution, they incorporated the Malay monarchy into the blueprints for the independent Federation of Malaya.

The social contract in Malaysia is a political construct first mooted in the 1980s, allegedly to justify the continuation of the discriminatory preferential policies for the majority Bumiputera at the expense of the non-Bumiputeras, most particularly the Chinese and the Indian citizens of the country. Generally describing the envisaged 20-year initial duration of the Malaysian New Economic Policy, proponents of the construct allege that it reflects an "understanding" arrived at – prior to Malaya's independence in 1957 – by the country's "founding fathers", which is an ill-defined term generally taken to encompass Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia's first Prime Minister, as well as V. T. Sambanthan and Tan Cheng Lock, who were the key leaders of political parties representing the Malay, Indian and Chinese populations respectively in pre-independence Malaya.

Tun Dr. Ismail bin Abdul Rahman was a Malaysian politician who served as the second Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia from September 1970 to his death in August 1973. A member of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), he previously held several ministerial posts.

During the 1960s in Malaysia and Singapore, some racial extremists were referred to as "ultras". The phrase was most commonly used by the first Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, and other leaders of his political party, the People's Action Party (PAP), to refer to Malay extremists. However, it was also used by some members of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) — the leader of the Alliance coalition governing Malaysia – to refer to Lee instead, as Lee was perceived to be a Chinese chauvinist himself.

Syed Jaafar Albar was a Malaysian politician. His staunch defence of his political party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) – which leads the governing Barisan Nasional coalition – led to him being given the moniker "Lion of UMNO". He was also known for his radical views on Malay sovereignty over Malaysia, and Malay supremacy in politics, and is of Hadhrami Arab descent. He was born in Celebes, Dutch East Indies and migrated when he was 14 years old to Singapore.

Singapore, officially the State of Singapore, was one of the 14 states of Malaysia from 1963 to 1965. Malaysia was formed on 16 September 1963 by the merger of the Federation of Malaya with the former British colonies of North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore. This marked the end of the 144-year British rule in Singapore which began with the founding of modern Singapore by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819. At the time of merger, it was the smallest state in the country by land area, but the largest by population.

Malay nationalism refers to the nationalism that focused overwhelmingly on the Malay anticolonial struggle, motivated by the nationalist ideal of creating a Bangsa Melayu. Its central objectives were the advancement and protection of Malayness: religion (Islam), language (Malay), and royalty. Such pre-occupation is a direct response to the European colonial presence and the influx of a foreign migrant population in Malaya since the mid-nineteenth century.

Tan Sri Dato' Sri Lee Kim Sai was a Malaysian politician. In the 1980s and 1990s, he served as Labour Minister (1985–1989), Housing and Local Government Minister (1989–1990) and Health Minister (1990–1995); and was deputy president of Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) (1986–1996), a major component party of the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition.

The Alliance Party was a political coalition in Malaysia. The Alliance Party, whose membership comprised United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), was formally registered as a political organisation on 30 October 1957. It was the ruling coalition of Malaya from 1957 to 1963, and Malaysia from 1963 to 1973. The coalition became the Barisan Nasional in 1973.