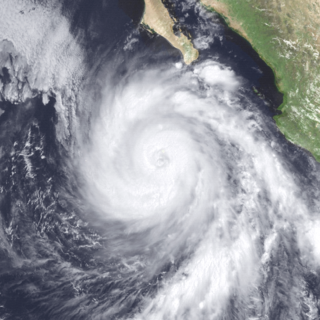

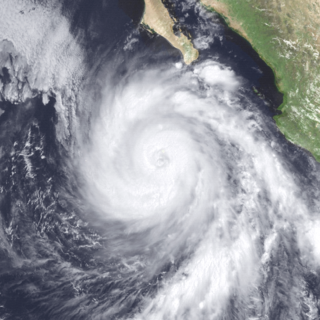

Hurricane Kathleen was a Category 1 Pacific hurricane that had a destructive impact in California. On September 7, 1976, a tropical depression formed; two days later it accelerated north towards the Baja California Peninsula. Kathleen brushed the Pacific coast of the peninsula as a hurricane on September 9 and made landfall as a fast-moving tropical storm the next day. With its circulation intact and still a tropical storm, Kathleen headed north into the United States and affected California and Arizona. Kathleen finally dissipated late on September 11.

Floods in the United States are generally caused by excessive rainfall, excessive snowmelt, and dam failure. Below is a list of flood events that were of significant impact to the country during the 20th century, from 1900 through 1999, inclusive.

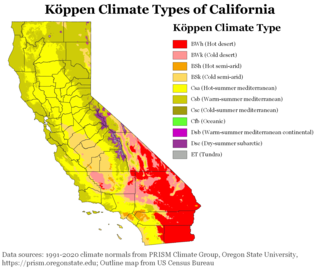

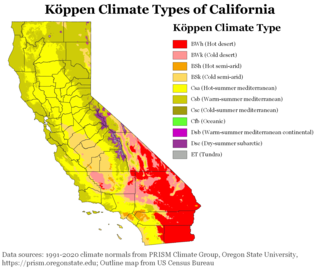

The climate of California varies widely from hot desert to alpine tundra, depending on latitude, elevation, and proximity to the Pacific Coast. California's coastal regions, the Sierra Nevada foothills, and much of the Central Valley have a Mediterranean climate, with warmer, drier weather in summer and cooler, wetter weather in winter. The influence of the ocean generally moderates temperature extremes, creating warmer winters and substantially cooler summers in coastal areas.

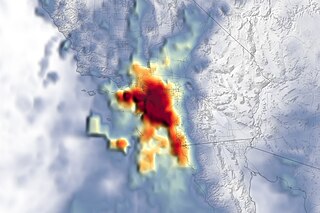

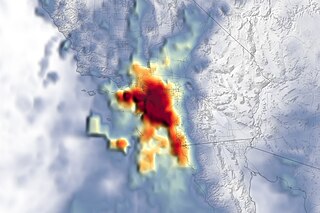

All types of floods can occur in California, though 90 percent of them are caused by river flooding in lowland areas. Such flooding generally occurs as a result of excessive rainfall, excessive snowmelt, excessive runoff, levee failure, poor planning or built infrastructure, or a combination of these factors. Below is a list of flood events that were of significant impact to California.

The Great Coastal Storm of 2007 was a series of three powerful Pacific storms that affected the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington and the Canadian province of British Columbia between December 1, 2007 and December 4, 2007.

The January 2008 North American storm complex was a powerful Pacific extratropical cyclone that affected a large portion of North America, primarily stretching from western British Columbia to near the Tijuana, Mexico area, starting on January 3, 2008. The system was responsible for flooding rains across many areas in California along with very strong winds locally exceeding hurricane force strength as well as heavy mountain snows across the Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountain chains as well as those in Idaho, Utah and Colorado. The storms were responsible for the death of at least 12 people across three states, and extensive damage to utility services as well, as damage to some other structures. The storm was also responsible for most of the January 2008 tornado outbreak from January 7–8.

Hurricane Norman was a rare tropical cyclone that impacted California in early September 1978. The fourteenth named storm, eleventh hurricane, and sixth major hurricane of the 1978 Pacific season, Norman originated from an tropical wave that spawned an area of disturbed weather south of Acapulco. The system coalesced into a tropical depression on August 30 and thrived amid favorable environmental conditions, becoming a powerful Category 4 hurricane with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) at its peak intensity. The system curved northward, passing into cooler waters that brought an end to its status as a tropical cyclone on September 6. However, its remnants combined with an trough and front over California, contributing to locally heavy rainfall that caused dozens of traffic accidents and sporadic power outages. In higher elevations, the system produced accumulating snow which stranded and killed many hikers throughout Sierra Nevada. Most heavily affected was California's raisin crop, which suffered a record-breaking 95 percent loss. Overall, Norman killed eight people and caused over $300 million in damage.

The October 2009 North American storm complex was a powerful extratropical cyclone that was associated with the remnants of Typhoon Melor, which brought extreme amounts of rainfall to California. The system started out as a weak area of low pressure, that formed in the northern Gulf of Alaska on October 7. Late on October 11, the system quickly absorbed Melor's remnant moisture, which resulted in the system strengthening significantly offshore, before moving southeastward to impact the West Coast of the United States, beginning very early on October 13. Around the same time, an atmospheric river opened up, channeling large amounts of moisture into the storm, resulting in heavy rainfall across California and other parts of the Western United States. The storm caused at least $8.861 million in damages across the West Coast of the United States.

Global storm activity of 2008 profiles the major worldwide storms, including blizzards, ice storms, and other winter events, from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2008. A winter storm is an event in which the dominant varieties of precipitation are forms that only occur at cold temperatures, such as snow or sleet, or a rainstorm where ground temperatures are cold enough to allow ice to form. It may be marked by strong wind, thunder and lightning, heavy precipitation, such as ice, or wind transporting some substance through the atmosphere. Major dust storms, Hurricanes, cyclones, tornados, gales, flooding and rainstorms are also caused by such phenomena to a lesser or greater existent.

Global weather activity of 2007 profiles the major worldwide weather events, including blizzards, ice storms, tornadoes, tropical cyclones, and other weather events, from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2007. Winter storms are events in which the dominant varieties of precipitation are formed during cold temperatures; they include snow or sleet, or a rainstorm where ground temperatures are cold enough to allow ice, including freezing rain, to form. Thehy may be marked by strong wind, thunder, lightning thunderstorms, heavy precipitation, including ice storm, wind transporting some substance through the atmosphere, including dust storms, snowstorms, and hail storms. Other major non winter events such as large dust storms, hurricanes, cyclones, tornados, gales, flooding, and rainstorms are also caused by such phenomena.

The Great Flood of 1862 was the largest flood in the recorded history of California, Oregon, and Nevada, inundating the western United States and portions of British Columbia and Mexico. It was preceded by weeks of continuous rains and snows that began in Oregon in November 1861 and continued into January 1862. This was followed by a record amount of rain from January 9–12, and contributed to a flood that extended from the Columbia River southward in western Oregon, and through California to San Diego, and extended as far inland as (now) Idaho in the Washington Territory, (now) Nevada and Utah in the Utah Territory, and (now) Arizona in the western New Mexico Territory. The event dumped an equivalent of 10 feet (3.0 m) of water in California, in the form of rain and snow, over a period of 43 days. Immense snowfalls in the mountains of far western North America caused more flooding in Idaho, Arizona, New Mexico, as well as in Baja California and Sonora, Mexico the following spring and summer, as the snow melted.

The January 2010 North American winter storms were a group of seven powerful winter storms that affected Canada and the Contiguous United States, particularly California. The storms developed from the combination of a strong El Niño episode, a powerful jet stream, and an atmospheric river that opened from the West Pacific Ocean into the Western Seaboard. The storms shattered multiple records across the Western United States, with the sixth storm breaking records for the lowest recorded air pressure in multiple parts of California, which was also the most powerful winter storm to strike the Southwestern United States in 140 years. The fourth, fifth, and sixth storms spawned several tornadoes across California, with at least 6 tornadoes confirmed in California ; the storms also spawned multiple waterspouts off the coast of California. The storms dumped record amounts of rain and snow in the Western United States, and also brought hurricane-force winds to the U.S. West Coast, causing flooding and wind damage, as well as triggering blackouts across California that cut the power to more than 1.3 million customers. The storms killed at least 10 people, and caused more than $66.879 million in damages.

The January 2018 American West floods occurred due to heavy precipitation in the Western United States. While wildfires in Southern California exacerbated the rain's effects there, other states, like Nevada, also experienced flooding.

The January 31 – February 3, 2021 nor'easter, also known as the 2021 Groundhog Day nor'easter, was a powerful, severe, and erratic nor'easter that impacted much of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada from February 1–3 with heavy snowfall, blizzard conditions, strong gusty winds, storm surge, and coastal flooding. The storm first developed as an extratropical cyclone off the West Coast of the United States on January 25, with the storm sending a powerful atmospheric river into West Coast states such as California, where very heavy rainfall, snowfall, and strong wind gusts were recorded, causing several hundred thousand power outages and numerous mudslides. The system moved ashore several days later, moving into the Midwest and dropping several inches of snow across the region. On February 1, the system developed into a nor'easter off the coast of the Northeastern U.S., bringing prolific amounts of snowfall to the region. Large metropolitan areas such as Boston and New York City saw as much as 18–24 inches (46–61 cm) of snow accumulations from January 31 to February 2, making it the worst snowstorm to affect the megalopolis since the January 2016 blizzard. It was given the unofficial name Winter Storm Orlena by The Weather Channel.

Hurricane Olivia was a powerful and destructive Category 4 hurricane, that brought damaging floods to California and Utah during September 1982. Olivia was the twenty-fourth tropical cyclone, eighteenth named storm, ninth hurricane, and fourth major hurricane of the active 1982 Pacific hurricane season. The storm was first noted as a tropical depression from a ship report off the southern coast of Mexico. Olivia then steadily intensified before becoming a Category 4 hurricane, and reaching its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of around 145 mph (230 km/h), at 18:00 UTC on September 21. The hurricane then rapidly weakened as it passed west of mainland Mexico, before being last noted to the west of California on September 25, as a surface trough.

An extremely powerful extratropical bomb cyclone began in late October 2021 in the Northeast Pacific and struck the Western United States and Western Canada. The storm was the third and the most powerful cyclone in a series of powerful storms that struck the region within a week. The cyclone tapped into a large atmospheric river and underwent explosive intensification, becoming a bomb cyclone on October 24. The bomb cyclone had a minimum central pressure of 942 millibars (27.8 inHg) at its peak, making it the most powerful cyclone recorded in the Northeast Pacific. The system had severe impacts across Western North America, before dissipating on October 26. The storm shattered multiple pressure records across parts of the Pacific Northwest. Additionally, the bomb cyclone was the most powerful storm on record to strike the region, in terms of minimum central pressure. The bomb cyclone brought powerful gale-force winds and flooding to portions of Western North America. At its height, the storm cut the power to over 370,500 customers across the Western U.S. and British Columbia. The storm killed at least two people; damage from the storm was estimated at several hundred million dollars. The bomb cyclone was compared to the Columbus Day Storm of 1962, in terms of ferocity.

Hurricane Kay was a Category 2 hurricane that made landfall along the Pacific coast of the Baja California peninsula as a tropical storm. The twelfth named storm and eighth hurricane of the 2022 Pacific hurricane season, Kay originated from an area of disturbed weather that formed south of southern Mexico. Overall, damage from Kay totaled $10.62 million and it was responsible for five fatalities. Rain from the storm proved beneficial for firefighters battling the Fairview Fire in Southern California.

Periods of heavy rainfall caused by multiple atmospheric rivers in California between December 31, 2022, and March 25, 2023, resulted in floods that affected parts of Southern California, the California Central Coast, Northern California and Nevada. The flooding resulted in property damage and at least 22 fatalities. At least 200,000 homes and businesses lost power during the December-January storms and 6,000 individuals were ordered to evacuate.

In early February 2024, two atmospheric rivers brought extensive flooding, intense winds, and power outages to portions of California. The storms caused record-breaking rainfall totals to be observed in multiple areas, as well as the declaration of states of emergency in multiple counties in Southern California. Wind gusts of hurricane force were observed in San Francisco, along with wind gusts reaching over 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Widespread landslides occurred as a result of the storms, as well as multiple rivers overflowing due to the excessive rainfall. Meteorologist Dr. Reed Timmer stated that "Biblical flooding" was possible throughout California during the atmospheric river.