Benigno "Ninoy" SimeonAquino Jr., was a Filipino politician who served as a senator of the Philippines (1967–1972) and governor of the province of Tarlac. Aquino was the husband of Corazon Aquino, who became the 11th president of the Philippines after his assassination, and father of Benigno Aquino III, who became the 15th president of the Philippines. Aquino, together with Gerardo Roxas and Jovito Salonga, helped form the leadership of the opposition towards then President Ferdinand Marcos. He was the significant leader who together with the intellectual leader Sen. Jose W. Diokno led the overall opposition.

Jovito Reyes Salonga, KGCR also called "Ka Jovy," was a Filipino politician and lawyer, as well as a leading opposition leader during the regime of Ferdinand Marcos from the declaration of martial law in 1972 until the People Power Revolution in 1986, which removed Marcos from power. Salonga was the 14th president of the Senate of the Philippines, serving from 1987 to 1992.

Jose Maria Canlas Sison, also known as Joma, was a Filipino writer, poet, and activist who founded and led the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and added elements of Maoism to its philosophy—which would be known as National Democracy. His ideology was formed by applying Marxism–Leninism–Maoism to the history and circumstances of the Philippines.

The First Quarter Storm, often shortened into the acronym FQS, was a period of civil unrest in the Philippines which took place during the "first quarter of the year 1970". It included a series of demonstrations, protests, and marches against the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos, mostly organized by students and supported by workers, peasants, and members of the urban poor, from January 26 to March 17, 1970. Protesters at these events raised issues related to social problems, authoritarianism, alleged election fraud, and corruption at the hand of Marcos.

Eva Estrada Kalaw was a Filipina politician who served as a senator in the Senate of the Philippines from 1965 to 1972 during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. She was one of the key opposition figures against Marcos' 20-year authoritarian rule and was instrumental in his downfall during the People Power Revolution in 1986. As a senator, she wrote several laws relating to education in the Philippines, such as the salary standardization for public school personnel, the Magna Carta for Private Schools, the Magna Carta for Students, and an act to institute a charter for Barrio High Schools. She was also among the Liberal Party candidates injured during the Plaza Miranda bombing on August 21, 1971.

The history of the Philippines, from 1965 to 1986, covers the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. The Marcos era includes the final years of the Third Republic (1965–1972), the Philippines under martial law (1972–1981), and the majority of the Fourth Republic (1981–1986). By the end of the Marcos dictatorial era, the country was experiencing a debt crisis, extreme poverty, and severe underemployment.

Jose "Lito" Livioko Atienza Jr. is a Filipino politician. He served as a Party-list Representative for Buhay from 2013 to 2022, and was a House Deputy Speaker from 2020 to 2022. He served as the Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources from 2007 to 2009 in the Administration of President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, and was 24th Mayor of Manila for three consecutive terms from 1998 to 2007. He unsuccessfully ran for vice president of the Philippines in the 2022 elections as the running mate of Senator Manny Pacquiao.

A senatorial election was held on November 8, 1971 in the Philippines. The opposition Liberal Party won five seats in the Philippine Senate while three seats were won by the Nacionalista Party, the administration party; this was seen as a consequence of the Plaza Miranda bombing on August 21, 1971, which wounded all of the Liberal Party's candidates and almost took the lives of John Henry Osmeña and Jovito Salonga. Their terms as senators were cut short as a result of the declaration of martial law by President Ferdinand Marcos on September 23, 1972.

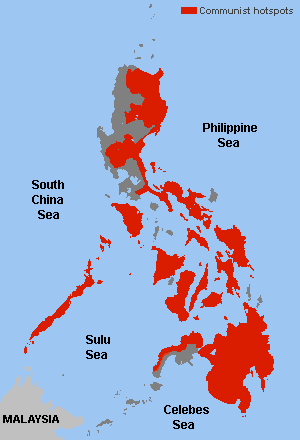

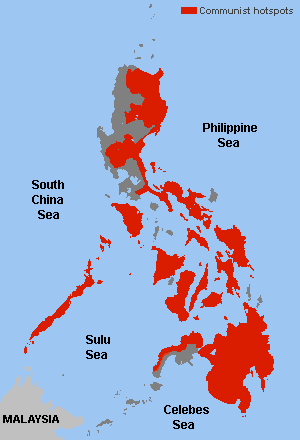

The New People's Army rebellion is an ongoing conflict between the government of the Philippines and the New People's Army (NPA), which is the armed wing of the Marxist–Leninist–Maoist Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). It is the world's longest ongoing communist insurgency, and is the largest, most prominent communist armed conflict in the Philippines, seeing more than 43,000 insurgency-related fatalities between 1969 and 2008. Because the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) which is the legal wing of the CPP, is often associated with the conflict, it is often also called the CPP-NPA-NDF conflict, or simply the C/N/N conflict, especially in the context of peace talks with the Philippine government.

Martial law in the Philippines refers to the various historical instances in which the Philippine head of state placed all or part of the country under military control—most prominently during the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, but also during the Philippines' colonial period, during the second world war, and more recently on the island of Mindanao during the administrations of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and Rodrigo Duterte. The alternative term "martial law era" as applied to the Philippines is typically used to describe the Marcos martial law period specifically.

Ramon Delaraga Bagatsing Sr. was a Filipino politician. He was the only Filipino of Indian ancestry and person with disability who served as 19th Mayor of the City of Manila from 1971 to 1986. Bagatsing held the unique distinction of being the only person to survive both the Bataan Death March and the Plaza Miranda bombing in 1971. He was the military hero for the Liberation of Manila during the Second World War.

Antonio de Jesus Villegas was a Filipino politician who served as the 18th Mayor of Manila from 1962 to 1971. His term was after the term of Arsenio Lacson as mayor of Manila, and before the period of martial law in the Philippines.

1971 in the Philippines details events of note that happened in the Philippines in the year 1971.

The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos is a 1976 memoir written in exile by former press censor and propagandist Primitivo Mijares. It details the inner workings of Philippine martial law under Ferdinand Marcos from the perspective of Mijares.

Communism in the Philippines emerged in the first half of the 20th century during the American Colonial Era of the Philippines. Communist movements originated in labor unions and peasant groups. The communist movement has had multiple periods of popularity and relevance to the national affairs of the country, most notably during the Second World War and the Martial Law Era of the Philippines. Currently the communist movement is underground and considered an insurgent movement by the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

The Aquino family of Tarlac is one of the most prominent families in the Philippines because of their involvement in politics. Some family members are also involved in other fields such as business and entertainment.

Student activism in the Philippines from 1965 to 1972 played a key role in the events which led to Ferdinand Marcos' declaration of Martial Law in 1972, and the Marcos regime's eventual downfall during the events of the People Power Revolution of 1986.

The Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties (MCCCL) is an advocacy coalition in the Philippines which was first formed under the leadership of José W. Diokno in 1971, as a response to the suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus in the wake of the Plaza Miranda bombing. It became well known for the series of rallies which it organized from 1971–72, especially the most massive one on September 21, 1972, hours before the imposition of martial law by the Marcos dictatorship.

Ferdinand Marcos' second term as President of the Philippines began on December 30, 1969, as a result of his winning the 1969 Philippine presidential election on November 11, 1969. Marcos was the first and last president of the Third Philippine Republic to win a second full term. The end of Marcos' second term was supposed to be in December 1973, which would also have been the end of his presidency because the 1935 Constitution of the Philippines allowed him to have only two four-year terms. However, Marcos issued Proclamation 1081 in September 1972, placing the entirety of the Philippines under Martial Law and effectively extending his term indefinitely. He would only be removed from the presidency in 1986, as a result of the People Power Revolution.