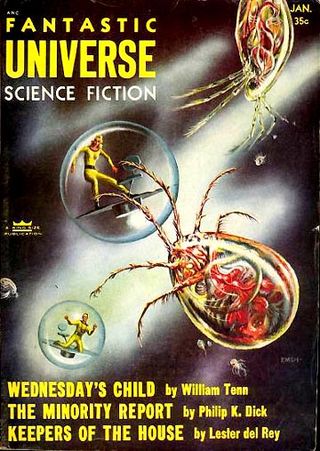

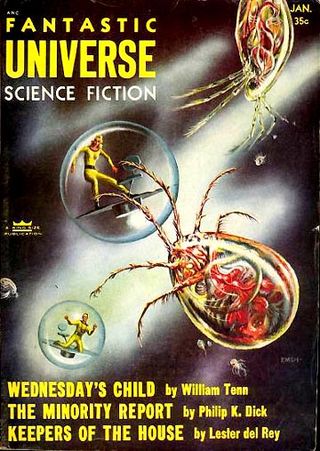

"The Minority Report" is a 1956 science fiction novella by American writer Philip K. Dick, first published in Fantastic Universe. In a future society, three mutants foresee all crime before it occurs. Plugged into a great machine, these "precogs" allow a division of the police called Precrime to arrest suspects before they can commit any actual crimes. When the head of Precrime, John Anderton, is himself predicted to murder a man whom he has never heard of, Anderton is convinced a great conspiracy is afoot.

Restorative justice is an approach to justice that aims to repair the harm done to victims. In doing so, practitioners work to ensure that offenders take responsibility for their actions, to understand the harm they have caused, to give them an opportunity to redeem themselves, and to discourage them from causing further harm. For victims, the goal is to give them an active role in the process, and to reduce feelings of anxiety and powerlessness.

Juvenile delinquency, also known as juvenile offending, is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as a minor or individual younger than the statutory age of majority. These acts would otherwise be considered crimes if the individuals committing them were older. The term delinquent usually refers to juvenile delinquency, and is also generalised to refer to a young person who behaves an unacceptable way.

Criminal psychology, also referred to as criminological psychology, is the study of the views, thoughts, intentions, actions and reactions of criminals and suspects. It is a subfield of criminology and applied psychology.

Recidivism is the act of a person repeating an undesirable behavior after they have experienced negative consequences of that behavior, or have been trained to extinguish it. Recidivism is also used to refer to the percentage of former prisoners who are rearrested for a similar offense.

Articles related to criminology and law enforcement.

Preventive detention is an imprisonment that is putatively justified for non-punitive purposes, most often to prevent further criminal acts.

A sex offender is a person who has committed a sex crime. What constitutes a sex crime differs by culture and legal jurisdiction. The majority of convicted sex offenders have convictions for crimes of a sexual nature; however, some sex offenders have simply violated a law contained in a sexual category. Some of the serious crimes which usually result in a mandatory sex-offender classification are sexual assault, statutory rape, bestiality, child sexual abuse, incest, rape, and sexual imposition.

Lucia ZednerFBA is a British legal scholar. She is a professor of criminal justice at the University of Oxford and a senior fellow of All Souls College, Oxford.

Incapacitation in the context of criminal sentencing philosophy is one of the functions of punishment. It involves capital punishment, sending an offender to prison, or possibly restricting their freedom in the community, to protect society and prevent that person from committing further crimes. Incarceration, as the primary mechanism for incapacitation, is also used as to try to deter future offending.

Pre-trial detention, also known as jail, preventive detention, provisional detention, or remand, is the process of detaining a person until their trial after they have been arrested and charged with an offence. A person who is on remand is held in a prison or detention centre or held under house arrest. Varying terminology is used, but "remand" is generally used in common law jurisdictions and "preventive detention" elsewhere. However, in the United States, "remand" is rare except in official documents and "jail" is instead the main terminology. Detention before charge is commonly referred to as custody and continued detention after conviction is referred to as imprisonment.

A preventive state is a type of sovereign state or policy enacted by a state in which people deemed potentially dangerous are apprehended, and have their freedom restricted, before being able to commit a crime. Insofar as it differs from passive attempts to prevent criminal behaviour, it has been referred to by Eric S. Janus as "radical prevention". Its opposite is the punitive state, or any punitive methods, under which criminals are punished after a criminal act has been committed. To the extent that punitive methods often involve incarceration, thereby preventing further crimes being committed by the individual, they can also be considered preventive; the penological theory justifying this is incapacitation. Michael L. Rich further defines as the "perfect preventive state" a situation in which targeted criminal conduct is made impossible by the mandates of government.

In the United States, the practice of predictive policing has been implemented by police departments in several states such as California, Washington, South Carolina, Alabama, Arizona, Tennessee, New York, and Illinois. Predictive policing refers to the usage of mathematical, predictive analytics, and other analytical techniques in law enforcement to identify potential criminal activity. Predictive policing methods fall into four general categories: methods for predicting crimes, methods for predicting offenders, methods for predicting perpetrators' identities, and methods for predicting victims of crime.

Criminal justice reform seeks to address structural issues in criminal justice systems such as racial profiling, police brutality, overcriminalization, mass incarceration, and recidivism. Reforms can take place at any point where the criminal justice system intervenes in citizens’ lives, including lawmaking, policing, sentencing and incarceration. Criminal justice reform can also address the collateral consequences of conviction, including disenfranchisement or lack of access to housing or employment, that may restrict the rights of individuals with criminal records.

The risk-needs-responsivity model is used in criminology to develop recommendations for how prisoners should be assessed based on the risk they present, what programs or services they require, and what kinds of environments they should be placed in to reduce recidivism. It was first proposed in 1990 based on the research conducted on classifications of offender treatments by Lee Sechrest and Ted Palmer, among other researchers, in the 1960s and 70s. It was primarily developed by Canadian researchers James Bonta, Donald A. Andrews, and Paul Gendreau. It has been considered the best model that exists for determining offender treatment, and some of the best risk-assessment tools used on offenders are based on it.

Grant Duwe is an American criminologist and research director at the Minnesota Department of Corrections, as well as a non-visiting scholar at Baylor University's Institute for Studies of Religion. Duwe holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Kansas and a Ph.D. in Criminology and Criminal Justice from Florida State University.

Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) is a case management and decision support tool developed and owned by Northpointe used by U.S. courts to assess the likelihood of a defendant becoming a recidivist.

Automated decision-making (ADM) involves the use of data, machines and algorithms to make decisions in a range of contexts, including public administration, business, health, education, law, employment, transport, media and entertainment, with varying degrees of human oversight or intervention. ADM involves large-scale data from a range of sources, such as databases, text, social media, sensors, images or speech, that is processed using various technologies including computer software, algorithms, machine learning, natural language processing, artificial intelligence, augmented intelligence and robotics. The increasing use of automated decision-making systems (ADMS) across a range of contexts presents many benefits and challenges to human society requiring consideration of the technical, legal, ethical, societal, educational, economic and health consequences.

Predictive policing is the usage of mathematics, predictive analytics, and other analytical techniques in law enforcement to identify potential criminal activity. A report published by the RAND Corporation identified four general categories predictive policing methods fall into: methods for predicting crimes, methods for predicting offenders, methods for predicting perpetrators' identities, and methods for predicting victims of crime.

Roderic Broadhurst is a criminal justice practitioner, academic, and author. He is an Emeritus Professor at the School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet) and Fellow of the Research School of Asian and the Pacific at the Australian National University (ANU).