Natural capital is the world's stock of natural resources, which includes geology, soils, air, water and all living organisms. Some natural capital assets provide people with free goods and services, often called ecosystem services. All of these underpin our economy and society, and thus make human life possible.

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests and woodlands for associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. The science of forestry has elements that belong to the biological, physical, social, political and managerial sciences. Forest management plays an essential role in the creation and modification of habitats and affects ecosystem services provisioning.

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or logs onto trucks or skeleton cars. In forestry, the term logging is sometimes used narrowly to describe the logistics of moving wood from the stump to somewhere outside the forest, usually a sawmill or a lumber yard. In common usage, however, the term may cover a range of forestry or silviculture activities.

Habitat conservation is a management practice that seeks to conserve, protect and restore habitats and prevent species extinction, fragmentation or reduction in range. It is a priority of many groups that cannot be easily characterized in terms of any one ideology.

A green economy is an economy that aims at reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities, and that aims for sustainable development without degrading the environment. It is closely related with ecological economics, but has a more politically applied focus. The 2011 UNEP Green Economy Report argues "that to be green, an economy must not only be efficient, but also fair. Fairness implies recognizing global and country level equity dimensions, particularly in assuring a Just Transition to an economy that is low-carbon, resource efficient, and socially inclusive."

Environmental resource management or environmental management is the management of the interaction and impact of human societies on the environment. It is not, as the phrase might suggest, the management of the environment itself. Environmental resources management aims to ensure that ecosystem services are protected and maintained for future human generations, and also maintain ecosystem integrity through considering ethical, economic, and scientific (ecological) variables. Environmental resource management tries to identify factors between meeting needs and protecting resources. It is thus linked to environmental protection, resource management, sustainability, integrated landscape management, natural resource management, fisheries management, forest management, wildlife management, environmental management systems, and others.

Ecological engineering uses ecology and engineering to predict, design, construct or restore, and manage ecosystems that integrate "human society with its natural environment for the benefit of both".

Ecosystem services are the various benefits that humans derive from healthy ecosystems. These ecosystems, when functioning well, offer such things as provision of food, natural pollination of crops, clean air and water, decomposition of wastes, or flood control. Ecosystem services are grouped into four broad categories of services. There are provisioning services, such as the production of food and water. Regulating services, such as the control of climate and disease. Supporting services, such as nutrient cycles and oxygen production. And finally there are cultural services, such as spiritual and recreational benefits. Evaluations of ecosystem services may include assigning an economic value to them.

Natural resource management (NRM) is the management of natural resources such as land, water, soil, plants and animals, with a particular focus on how management affects the quality of life for both present and future generations (stewardship).

A green-collar worker is a worker who is employed in an environmental sector of the economy. Environmental green-collar workers satisfy the demand for green development. Generally, they implement environmentally conscious design, policy, and technology to improve conservation and sustainability. Formal environmental regulations as well as informal social expectations are pushing many firms to seek professionals with expertise with environmental, energy efficiency, and clean renewable energy issues. They often seek to make their output more sustainable, and thus more favorable to public opinion, governmental regulation, and the Earth's ecology.

Ecotrust is a nonprofit organization based in Portland, Oregon, working to create social, economic, and environmental benefit.

Green jobs are, according to the United Nations Environment Program, "work in agricultural, manufacturing, research and development (R&D), administrative, and service activities that contribute(s) substantially to preserving or restoring environmental quality. Specifically, but not exclusively, this includes jobs that help to protect ecosystems and biodiversity; reduce energy, materials, and water consumption through high efficiency strategies; de-carbonize the economy; and minimize or altogether avoid generation of all forms of waste and pollution." The environmental sector has the dual benefit of mitigating environmental challenges as well as helping economic growth.

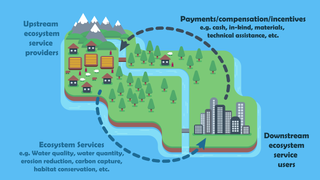

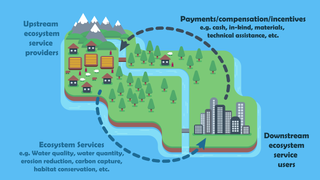

Payments for ecosystem services (PES), also known as payments for environmental services, are incentives offered to farmers or landowners in exchange for managing their land to provide some sort of ecological service. They have been defined as "a transparent system for the additional provision of environmental services through conditional payments to voluntary providers". These programmes promote the conservation of natural resources in the marketplace.

The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) was a study led by Pavan Sukhdev from 2007 to 2011. It is an international initiative to draw attention to the global economic benefits of biodiversity. Its objective is to highlight the growing cost of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation and to draw together expertise from the fields of science, economics and policy to enable practical actions. TEEB aims to assess, communicate and mainstream the urgency of actions through its five deliverables—D0: science and economic foundations, policy costs and costs of inaction, D1: policy opportunities for national and international policy-makers, D2: decision support for local administrators, D3: business risks, opportunities and metrics and D4: citizen and consumer ownership.

Earth Economics is a 501(c)(3) non-profit formally established in 2004 and headquartered in Tacoma, Washington, United States. The organization uses natural capital valuation to help decision makers and local stakeholders to understand the value of natural capital assets. By identifying, monetizing, and valuing natural capital and ecosystem services.

Forest restoration is defined as "actions to re-instate ecological processes, which accelerate recovery of forest structure, ecological functioning and biodiversity levels towards those typical of climax forest", i.e. the end-stage of natural forest succession. Climax forests are relatively stable ecosystems that have developed the maximum biomass, structural complexity and species diversity that are possible within the limits imposed by climate and soil and without continued disturbance from humans. Climax forest is therefore the target ecosystem, which defines the ultimate aim of forest restoration. Since climate is a major factor that determines climax forest composition, global climate change may result in changing restoration aims. Additionally, the potential impacts of climate change on restoration goals must be taken into account, as changes in temperature and precipitation patterns may alter the composition and distribution of climax forests.

Pavan Sukhdev is an Indian environmental economist whose field of studies include green economy and international finance. He was the Special Adviser and Head of UNEP's Green Economy Initiative, a major UN project suite to demonstrate that greening of economies is not a burden on growth but rather a new engine for growing wealth, increasing decent employment, and reducing persistent poverty. Pavan was also the Study Leader for the ground breaking TEEB study commissioned by G8+5 and hosted by UNEP. Under his leadership, TEEB sized the global problem of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation in economic and human welfare terms, and proposed solutions targeted at policy-makers, administrators, businesses and citizens. TEEB presented its widely acclaimed Final Report suite at the UN meeting by Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in Nagoya, Japan.

Deforestation in British Columbia has resulted in a net loss of 1.06 million hectares of tree cover between the years 2000 and 2020. More traditional losses have been exacerbated by increased threats from climate change driven fires, increased human activity, and invasive species. The introduction of sustainable forestry efforts such as the Zero Net Deforestation Act seeks to reduce the rate of forest cover loss. In British Columbia, forests cover over 55 million hectares, which is 57.9% of British Columbia's 95 million hectares of land. The forests are mainly composed of coniferous trees, such as pines, spruces and firs.

The H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, commonly referred to as Andrews Forest, is located near Blue River, Oregon, United States, and is managed cooperatively by the United States Forest Service's Pacific Northwest Research Station, Oregon State University, and the Willamette National Forest. It was one of only 610 UNESCO International Biosphere Reserves, until being withdrawn from the program as of June 14, 2017, and a Long Term Ecological Research site. It is situated in the middle of the Western Cascades.

Natural capital accounting is the process of calculating the total stocks and flows of natural resources and services in a given ecosystem or region. Accounting for such goods may occur in physical or monetary terms. This process can subsequently inform government, corporate and consumer decision making as each relates to the use or consumption of natural resources and land, and sustainable behaviour.