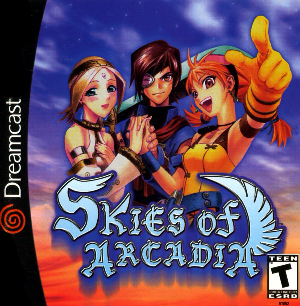

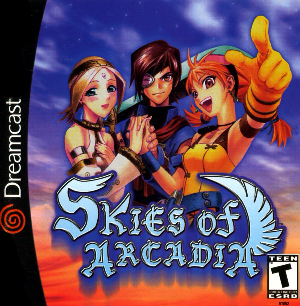

Skies of Arcadia is a 2000 Dreamcast role-playing video game developed by Overworks and published by Sega. Players control Vyse, a young air pirate, and his friends as they attempt to stop the Valuan Empire from reviving ancient weapons with the potential to destroy the world.

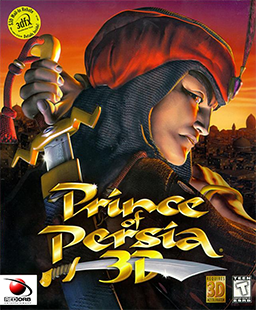

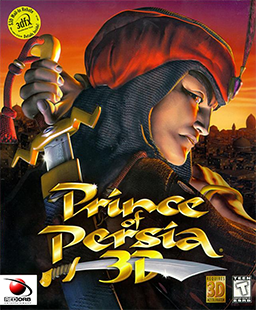

Prince of Persia 3D is a 1999 action-adventure video game developed by Mindscape, and published by Red Orb Entertainment for Microsoft Windows. A port for the Dreamcast was developed by Avalanche Software and published by Mattel Interactive in North America the following year under the title Prince of Persia: Arabian Nights. It is the first 3D installment in the Prince of Persia series, and the final game in the trilogy that started with the original 1989 game. Taking the role of the titular unnamed character rescuing his bride from a monstrous suitor's schemes, gameplay follows the Prince as he explores environments, platforming and solving puzzles while engaging in combat scenarios.

Fighting Force is a 1997 3D brawler developed by Core Design and published by Eidos. It was released for PlayStation, Microsoft Windows, and Nintendo 64 on 15 October 1997. Announced shortly after Core became a star developer through the critical and commercial success of Tomb Raider, Fighting Force was highly anticipated but met with mixed reviews.

Nightmare Creatures is a 1997 survival horror video game developed by Kalisto Entertainment for PlayStation, Microsoft Windows and Nintendo 64. A sequel, Nightmare Creatures II, was released three years later. A mobile phone version of Nightmare Creatures was developed and published by Gameloft in 2003. A second sequel, Nightmare Creatures III: Angel of Darkness, was cancelled in 2004.

Fighter Maker(格闘ツクール, Kakutō Tsukūru) is a series of games for PlayStation consoles and Microsoft Windows. It features a robust character creation system, letting players even create animations. There are two versions of the games, Fighter Maker and 2D Fighter Maker.

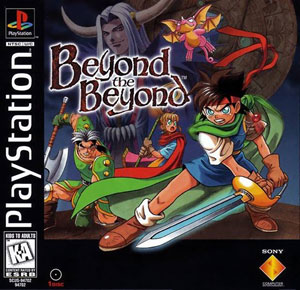

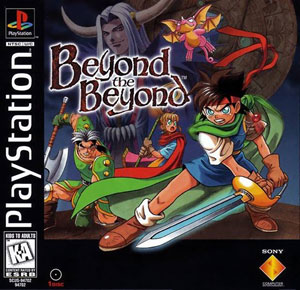

Beyond the Beyond, known in Japan as Beyond the Beyond: Harukanaru Kanān e, is a role-playing video game that was developed by Camelot Software Planning and published by Sony Computer Entertainment for the PlayStation in 1995. Though not the first role-playing game released for the PlayStation, Beyond the Beyond was the first RPG available in the west for the console using a traditional Japanese RPG gameplay style like Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest and Phantasy Star. The characters were designed by popular manga artist Ami Shibata.

Armored Core: Project Phantasma is a 1997 third-person shooter mecha video game developed by FromSoftware for the PlayStation. Project Phantasma is the second entry in the Armored Core series and a prequel to the original Armored Core. The game was not released in Europe.

Armada is a video game developed and published by Metro3D. It was released for the Sega Dreamcast in North America on November 26, 1999. Armada is a shooter role-playing game (RPG) that allows up to four players to fly about the universe, fighting the enemy, performing missions and improving their ship.

WWF War Zone is a professional wrestling video game developed by Iguana West and released by Acclaim Entertainment in 1998 for the PlayStation, Nintendo 64, and Game Boy. The game features wrestlers from the World Wrestling Federation.

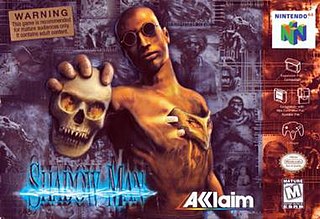

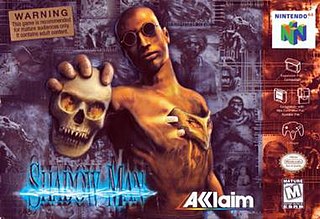

Shadow Man is an action-adventure video game developed by Acclaim Studios Teesside and published by Acclaim Entertainment. It is based on the Shadow Man comic book series published by Valiant Comics. The game was announced in 1997 and was originally slated for a late 1998 release on Nintendo 64 and an early 1999 release for Microsoft Windows, but was delayed to August 31, 1999. A PlayStation version was also released on the same day. A Dreamcast version was released three months later on December 1.

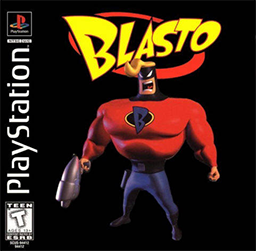

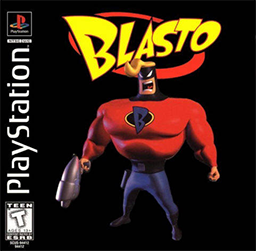

Blasto is a third-person shooter platform game developed by Sony Interactive Studios America and published by Sony Computer Entertainment for the PlayStation in 1998. Phil Hartman voiced Captain Blasto, an extremely muscular, alien-fighting, dimwitted captain.

Centipede is a 3D remake of the 1981 Centipede arcade game from Atari, the original of which was and designed by Ed Logg and Dona Bailey. It was published by Hasbro Interactive in 1998 under the Atari Interactive brand name.

Pitfall 3D: Beyond the Jungle, known as Pitfall: Beyond the Jungle in Europe, is a platform game developed by Activision's internal Console Development Group and published by Activision in 1998 for the PlayStation and by Crave Entertainment for the Game Boy Color in 1999. The game is part of the Pitfall series, following the 1994 installment Pitfall: The Mayan Adventure. It was first unveiled in 1996, when 3D platform gaming was still in its infancy, making designing the game a challenge. The PlayStation version development team included staff from the Virtua Fighter series, which was a pioneer in 3D gaming, but personnel changes led to Pitfall 3D being repeatedly delayed, and upon release critics sharply disagreed over whether it was a successful effort at bringing Pitfall into 3D.

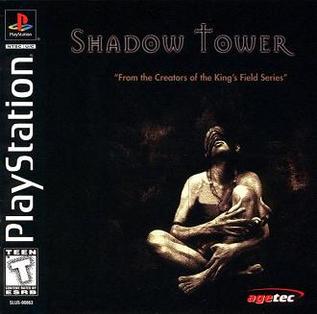

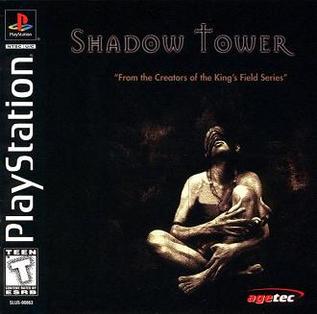

Shadow Tower is a 1998 action role-playing video game developed by FromSoftware for the PlayStation. The game was originally released in Japan by FromSoftware on June 25, 1998 and in North America by Agetec on November 23, 1999. Shadow Tower shares many similarities with the King's Field series of video games. A sequel, Shadow Tower Abyss, was released for the PlayStation 2 exclusively in Japan.

Assault, known in North America as Assault: Retribution, is a 1998 action video game developed by Candle Light Studios for the PlayStation console. It was published in North America by Midway Games and in Europe by Telstar.

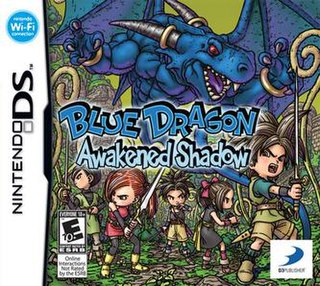

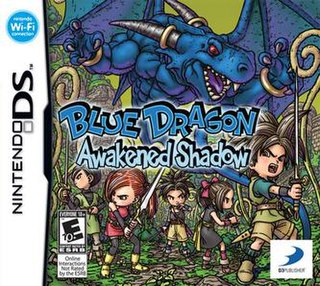

Blue Dragon: Awakened Shadow is an action role-playing video game developed by Mistwalker and tri-Crescendo and published by Namco Bandai in Japan and Europe and D3 Publisher in North America, for the Nintendo DS video game console and is part of the Blue Dragon series, its third installment and is a direct sequel to both Blue Dragon and Blue Dragon Plus. Hironobu Sakaguchi, Akira Toriyama and Hideo Baba are involved in the development of the game. It was released in Japan on October 8, 2009, in North America on May 18, 2010, and in the PAL region in September of the same year.

Ninja: Shadow of Darkness is an action beat 'em up platform video game developed by Core Design and published by Eidos Interactive for the PlayStation. The story follows a warrior named Kurosawa, who is tasked of ridding Feudal Japan of an unspeakable evil.

NCAA March Madness 2000 is the 1999 installment in the NCAA March Madness series. Former Maryland player Steve Francis is featured on the cover.

NCAA March Madness 99 is the 1998 installment in the NCAA March Madness series. Former North Carolina player Antawn Jamison is featured on the cover.

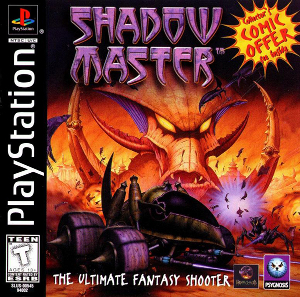

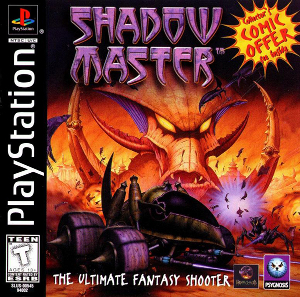

Shadow Master is a video game developed by HammerHead and published by Psygnosis for the PlayStation and Microsoft Windows. It is a first-person shooter in which the player character rides in an armed vehicle. It met with predominantly negative reviews which praised its visuals but criticized it for clunky controls and poorly designed, frustrating gameplay.