Coppicing is the traditional method in woodland management of cutting down a tree to a stump, which in many species encourages new shoots to grow from the stump or roots, thus ultimately regrowing the tree. A forest or grove that has been subject to coppicing is called a copse or coppice, in which young tree stems are repeatedly cut down to near ground level. The resulting living stumps are called stools. New growth emerges, and after a number of years, the coppiced trees are harvested, and the cycle begins anew. Pollarding is a similar process carried out at a higher level on the tree in order to prevent grazing animals from eating new shoots. Daisugi, is a similar Japanese technique.

Pollarding is a pruning system involving the removal of the upper branches of a tree, which promotes the growth of a dense head of foliage and branches. In ancient Rome, Propertius mentioned pollarding during the 1st century BCE. The practice has occurred commonly in Europe since medieval times, and takes place today in urban areas worldwide, primarily to maintain trees at a determined height or to place new shoots out of the reach of grazing animals.

In agriculture, rotational grazing, as opposed to continuous grazing, describes many systems of pasturing, whereby livestock are moved to portions of the pasture, called paddocks, while the other portions rest. Each paddock must provide all the needs of the livestock, such as food, water and sometimes shade and shelter. The approach often produces lower outputs than more intensive animal farming operations, but requires lower inputs, and therefore sometimes produces higher net farm income per animal.

Fraxinus excelsior, known as the ash, or European ash or common ash to distinguish it from other types of ash, is a flowering plant species in the olive family Oleaceae. It is native throughout mainland Europe east to the Caucasus and Alborz mountains, and Great Britain and Ireland, the latter determining its western boundary. The northernmost location is in the Trondheimsfjord region of Norway. The species is widely cultivated and reportedly naturalised in New Zealand and in scattered locales in the United States and Canada.

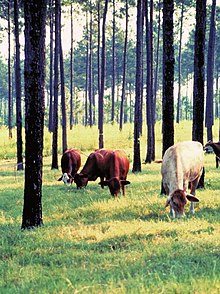

The longleaf pine is a pine species native to the Southeastern United States, found along the coastal plain from East Texas to southern Virginia, extending into northern and central Florida. In this area it is also known as "yellow pine" or "long leaf yellow pine", although it is properly just one out of a number of species termed yellow pine. It reaches a height of 30–35 m (98–115 ft) and a diameter of 0.7 m (28 in). In the past, before extensive logging, they reportedly grew to 47 m (154 ft) with a diameter of 1.2 m (47 in). The tree is a cultural symbol of the Southern United States, being the official state tree of Alabama. This particular species is one of the eight pine tree species that falls under the "Pine" designation as the state tree of North Carolina.

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are allowed outdoors to free range and consume wild vegetations in order to convert the otherwise indigestible cellulose within grass and other forages into meat, milk, wool and other animal products, often on land that is unsuitable for arable farming.

Rangelands are grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, wetlands, and deserts that are grazed by domestic livestock or wild animals. Types of rangelands include tallgrass and shortgrass prairies, desert grasslands and shrublands, woodlands, savannas, chaparrals, steppes, and tundras. Rangelands do not include forests lacking grazable understory vegetation, barren desert, farmland, or land covered by solid rock, concrete and/or glaciers.

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The animal species involved include cattle, camels, goats, yaks, llamas, reindeer, horses, and sheep.

In the United Kingdom, ancient woodland is that which has existed continuously since 1600 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Planting of woodland was uncommon before those dates, so a wood present in 1600 is likely to have developed naturally.

Agroforestry is a land use management system that integrates trees with crops or pasture. It combines agricultural and forestry technologies. As a polyculture system, an agroforestry system can produce timber and wood products, fruits, nuts, other edible plant products, edible mushrooms, medicinal plants, ornamental plants, animals and animal products, and other products from both domesticated and wild species.

Cytisus proliferus, tagasaste or tree lucerne, is a small spreading evergreen tree that grows 3–4 m (10–13 ft) high. It is a well known fertilizer tree. It is a member of the Fabaceae (pea) family and is indigenous to the dry volcanic slopes of the Canary Islands, but it is now grown in Australia, New Zealand and many other parts of the world as a fodder crop.

Farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) is a low-cost, sustainable land restoration technique used to combat poverty and hunger amongst poor subsistence farmers in developing countries by increasing food and timber production, and resilience to climate extremes. It involves the systematic regeneration and management of trees and shrubs from tree stumps, roots and seeds. FMNR was developed by the Australian agricultural economist Tony Rinaudo in the 1980s in West Africa. The background and development are described in Rinaudo's book The Forest Underground.

Forest farming is the cultivation of high-value specialty crops under a forest canopy that is intentionally modified or maintained to provide shade levels and habitat that favor growth and enhance production levels. Forest farming encompasses a range of cultivated systems from introducing plants into the understory of a timber stand to modifying forest stands to enhance the marketability and sustainable production of existing plants.

Conservation grazing or targeted grazing is the use of semi-feral or domesticated grazing livestock to maintain and increase the biodiversity of natural or semi-natural grasslands, heathlands, wood pasture, wetlands and many other habitats. Conservation grazing is generally less intensive than practices such as prescribed burning, but still needs to be managed to ensure that overgrazing does not occur. The practice has proven to be beneficial in moderation in restoring and maintaining grassland and heathland ecosystems. The optimal level of grazing will depend on the goal of conservation, and different levels of grazing, alongside other conservation practices, can be used to induce the desired results.

Deforestation is a major threat to biodiversity and ecosystems in Costa Rica. The country has a rich biodiversity with some 12,000 species of plants, 1,239 species of butterflies, 838 species of birds, 440 species of reptiles and amphibians, and 232 species of mammals, which have been under threat from the effects of deforestation. Agricultural development, cattle ranching, and logging have caused major deforestation as more land is cleared for these activities. Despite government efforts to mitigate deforestation, it continues to cause harm to the environment of Costa Rica by impacting flooding, soil erosion, desertification, and loss of biodiversity.

Albizia canescens, commonly known as Belmont siris, is a species of Albizia, endemic to Northern Australia.

The history of the forest in Central Europe is characterised by thousands of years of exploitation by people. Thus a distinction needs to be made between the botanical natural history of the forest in pre- and proto-historical times—which falls mainly into the fields of natural history and Paleobotany—and the onset of the period of sedentary settlement which began at the latest in the Neolithic era in Central Europe - and thus the use of the forest by people, which is covered by the disciplines of history, archaeology, cultural studies and ecology.

This glossary of agriculture is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in agriculture, its sub-disciplines, and related fields, including horticulture, animal husbandry, agribusiness, and agricultural policy. For other glossaries relevant to agricultural science, see Glossary of biology, Glossary of ecology, Glossary of environmental science, and Glossary of botanical terms.

A chestnut orchard is an open stand of grafted chestnut trees for fruit production. In this agroforestry system, trees are usually intercropped with cereals, hay or pasture. These orchards are traditional systems in Canton of Ticino (Switzerland) and Northern Italy, where they are called “selva castanile”. Similar systems can also be found in the Mediterranean region, for example, in France, Greece, Portugal or Spain.

Tree hay is a source of animal fodder produced by harvesting the leaves and twigs of a variety of perennials, and in particular trees. It specifically refers to the practice of feeding the material to livestock directly after collection or more commonly after storing and sometimes drying the tree hay for a certain period of time. It hence does not include the browsing of trees and fodder hedges by livestock directly.