The white stork is a large bird in the stork family, Ciconiidae. Its plumage is mainly white, with black on the bird's wings. Adults have long red legs and long pointed red beaks, and measure on average 100–115 cm (39–45 in) from beak tip to end of tail, with a 155–215 cm (61–85 in) wingspan. The two subspecies, which differ slightly in size, breed in Europe, northwestern Africa, southwestern Asia and southern Africa. The white stork is a long-distance migrant, wintering in Africa from tropical Sub-Saharan Africa to as far south as South Africa, or on the Indian subcontinent. When migrating between Europe and Africa, it avoids crossing the Mediterranean Sea and detours via the Levant in the east or the Strait of Gibraltar in the west, because the air thermals on which it depends for soaring do not form over water.

The black stork is a large bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae. Measuring on average 95 to 100 cm from beak tip to end of tail with a 145-to-155 cm (57-to-61 in) wingspan, the adult black stork has mainly black plumage, with white underparts, long red legs and a long pointed red beak. A widespread but uncommon species, it breeds in scattered locations across Europe, and east across the Palearctic to the Pacific Ocean. It is a long-distance migrant, with European populations wintering in tropical Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asian populations in the Indian subcontinent. When migrating between Europe and Africa, it avoids crossing broad expanses of the Mediterranean Sea and detours via the Levant in the east, the Strait of Sicily in the center, or the Strait of Gibraltar in the west. An isolated, non-migratory, population occurs in Southern Africa.

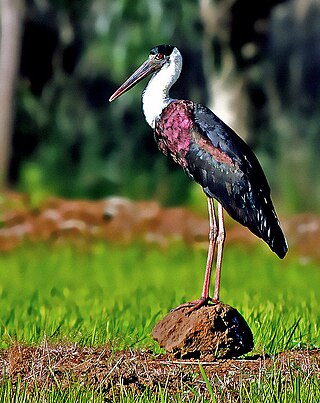

The Asian woolly-necked stork or Asian woollyneck is a species of large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. It breeds singly, or in small loose colonies. It is distributed in a wide variety of habitats including marshes in forests, agricultural areas, and freshwater wetlands across Asia.

The lesser adjutant is a large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. Like other members of its genus, it has a bare neck and head. It is however more closely associated with wetland habitats where it is solitary and is less likely to scavenge than the related greater adjutant. It is a widespread species found from India through Southeast Asia to Java.

The black-necked stork is a tall long-necked wading bird in the stork family. It is a resident species across the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia with a disjunct population in Australia. It lives in wetland habitats and near fields of certain crops such as rice and wheat where it forages for a wide range of animal prey. Adult birds of both sexes have a heavy bill and are patterned in white and irridescent blacks, but the sexes differ in the colour of the iris with females sporting yellow irises and males having dark-coloured irises. In Australia, it is known as a jabiru although that name refers to a stork species found in the Americas. It is one of the few storks that are strongly territorial when feeding and breeding.

The painted stork is a large wader in the stork family. It is found in the wetlands of the plains of tropical Asia south of the Himalayas in the Indian Subcontinent and extending into Southeast Asia. Their distinctive pink tertial feathers of the adults give them their name. They forage in flocks in shallow waters along rivers or lakes. They immerse their half open beaks in water and sweep them from side to side and snap up their prey of small fish that are sensed by touch. As they wade along they also stir the water with their feet to flush hiding fish. They nest colonially in trees, often along with other waterbirds. The only sounds they produce are weak moans or bill clattering at the nest. They are not migratory and only make short-distance movements in some parts of their range in response to changes in weather or food availability or for breeding. Like other storks, they are often seen soaring on thermals.

The wood stork is a large American wading bird in the family Ciconiidae (storks), the only member of the family to breed in North America. It was formerly called the "wood ibis", although it is not an ibis. It is found in subtropical and tropical habitats in the Americas, including the Caribbean. In South America, it is resident, but in North America, it may disperse as far as Florida. Originally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, this stork likely evolved in tropical regions. The head and neck are bare of feathers, and dark grey in colour. The plumage is mostly white, with the exception of the tail and some of the wing feathers, which are black with a greenish-purplish sheen. The juvenile differs from the adult, with the former having a feathered head and a yellow bill, compared to the black adult bill. There is very little sexual dimorphism.

The Asian openbill or Asian openbill stork is a large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. This distinctive stork is found mainly in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It is greyish or white with glossy black wings and tail and the adults have a gap between the arched upper mandible and recurved lower mandible. Young birds are born without this gap which is thought to be an adaptation that aids in the handling of snails, their main prey. Although resident within their range, they make long distance movements in response to weather and food availability.

The jabiru is a large stork found in the Americas from Mexico to Argentina, except west of the Andes. It sometimes wanders into the United States, usually in Texas, but has also been reported in Mississippi, Oklahoma and Louisiana. It is most common in the Pantanal region of Brazil and the Eastern Chaco region of Paraguay. It is the only member of the genus Jabiru. The name comes from the Tupi–Guaraní language and means "swollen neck".

The saddle-billed stork or saddlebill is a large wading bird in the stork family, Ciconiidae. It is a widespread species which is a resident breeder in sub-Saharan Africa from Sudan, Ethiopia and Kenya south to South Africa, and in The Gambia, Senegal, Côte d'Ivoire and Chad in west Africa. It is considered endangered in South Africa.

Ephippiorhynchus is a small genus of storks. It contains two living species only, very large birds more than 140 cm tall with a 230–270 cm wingspan. Both are mainly black and white, with huge bills. The sexes of these species are similarly plumaged, but the eyes are dark brown in males and yellow in females. The members of this genus are sometimes called "jabirus", but this properly refers to a close relative from Latin America.

The milky stork is a stork species found predominantly in coastal mangroves around parts of Southeast Asia. It is native to parts of Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia. They were once part of the genus Ibis, but is currently included in the genus Mycteria, due to similarities with other storks in that genus.

Mycteria is a genus of large tropical storks with representatives in the Americas, east Africa and southern and southeastern Asia. Two species have "ibis" in their scientific or old common names, but they are not related to these birds and simply look more similar to an ibis than do other storks.

The greater adjutant is a member of the stork family, Ciconiidae. Its genus includes the lesser adjutant of Asia and the marabou stork of Africa. Once found widely across southern Asia and mainland southeast Asia, the greater adjutant is now restricted to a much smaller range with only three breeding populations; two in India, with the largest colony in Assam, a smaller one around Bhagalpur; and another breeding population in Cambodia. They disperse widely after the breeding season. This large stork has a massive wedge-shaped bill, a bare head and a distinctive neck pouch. During the day, it soars in thermals along with vultures with whom it shares the habit of scavenging. They feed mainly on carrion and offal; however, they are opportunistic and will sometimes prey on vertebrates. The English name is derived from their stiff "military" gait when walking on the ground. Large numbers once lived in Asia, but they have declined to the point of endangerment. The total population in 2008 was estimated at around a thousand individuals. In the 19th century, they were especially common in the city of Calcutta, where they were referred to as the "Calcutta adjutant" and included in the coat of arms for the city. Known locally as hargila and considered to be unclean birds, they were largely left undisturbed but sometimes hunted for the use of their meat in folk medicine. Valued as scavengers, they were once depicted in the logo of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation.

Ciconia is a genus of birds in the stork family. Six of the seven living species occur in the Old World, but the maguari stork has a South American range. In addition, fossils suggest that Ciconia storks were somewhat more common in the tropical Americas in prehistoric times.

The African openbill is a species of stork from the family Ciconiidae. It is widely distributed in Sub-Saharan Africa and western regions of Madagascar. This species is considered common to locally abundant across its range, although it has a patchy distribution. Some experts consider there to be two sub-species, A. l. lamelligerus distributed on the continent and A. l. madagascariensis living on the island of Madagascar. Scientists distinguish between the two sub-species due to the more pronounced longitudinal ridges on the bills of adult A. l. madagascariensis. The Asian openbill found in Asia is the African openbill’s closest relative. The two species share the same notably large bill of a peculiar shape that gives them their name.

The maguari stork is a large species of stork that inhabits seasonal wetlands over much of South America, and is very similar in appearance to the white stork; albeit slightly larger. It is the only species of its genus to occur in the New World and is one of the only three New World stork species, together with the wood stork and the jabiru.

Jabiru codorensis is an extinct species of stork related to the extant Jabiru. It lived in what is now Venezuela during the Pliocene period and appears to have been similar to its modern relative.

The African woolly-necked stork or African woollyneck is a species of large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. It breeds singly, or in small loose colonies. It is distributed in a wide variety of habitats including marshes in forests, agricultural areas, and freshwater wetlands across Africa.