In physics, the Coriolis force is an inertial force that acts on objects in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame. In a reference frame with clockwise rotation, the force acts to the left of the motion of the object. In one with anticlockwise rotation, the force acts to the right. Deflection of an object due to the Coriolis force is called the Coriolis effect. Though recognized previously by others, the mathematical expression for the Coriolis force appeared in an 1835 paper by French scientist Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis, in connection with the theory of water wheels. Early in the 20th century, the term Coriolis force began to be used in connection with meteorology.

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal.

In physics, gravity (from Latin gravitas 'weight') is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things that have mass. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong interaction, 1036 times weaker than the electromagnetic force and 1029 times weaker than the weak interaction. As a result, it has no significant influence at the level of subatomic particles. However, gravity is the most significant interaction between objects at the macroscopic scale, and it determines the motion of planets, stars, galaxies, and even light.

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity. When the cause of the convection is unspecified, convection due to the effects of thermal expansion and buoyancy can be assumed. Convection may also take place in soft solids or mixtures where particles can flow.

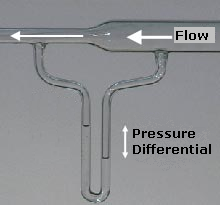

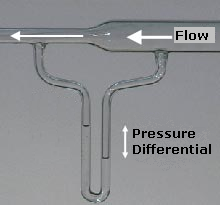

Bernoulli's principle is a key concept in fluid dynamics that relates pressure, speed and height. Bernoulli's principle states that an increase in the speed of a fluid occurs simultaneously with a decrease in static pressure or the fluid's potential energy. The principle is named after the Swiss mathematician and physicist Daniel Bernoulli, who published it in his book Hydrodynamica in 1738. Although Bernoulli deduced that pressure decreases when the flow speed increases, it was Leonhard Euler in 1752 who derived Bernoulli's equation in its usual form.

A centrifuge is a device that uses centrifugal force to subject a specimen to a specified constant force, for example to separate various components of a fluid. This is achieved by spinning the fluid at high speed within a container, thereby separating fluids of different densities or liquids from solids. It works by causing denser substances and particles to move outward in the radial direction. At the same time, objects that are less dense are displaced and moved to the centre. In a laboratory centrifuge that uses sample tubes, the radial acceleration causes denser particles to settle to the bottom of the tube, while low-density substances rise to the top. A centrifuge can be a very effective filter that separates contaminants from the main body of fluid.

In physics, the dynamo theory proposes a mechanism by which a celestial body such as Earth or a star generates a magnetic field. The dynamo theory describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can maintain a magnetic field over astronomical time scales. A dynamo is thought to be the source of the Earth's magnetic field and the magnetic fields of Mercury and the Jovian planets.

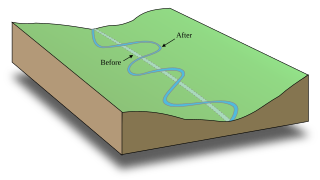

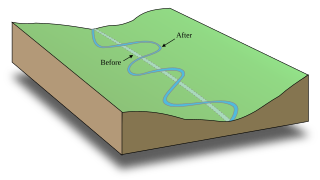

An oxbow lake is a U-shaped lake or pool that forms when a wide meander of a river is cut off, creating a free-standing body of water. The word "oxbow" can also refer to a U-shaped bend in a river or stream, whether or not it is cut off from the main stream.

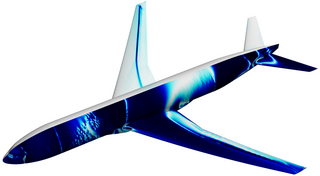

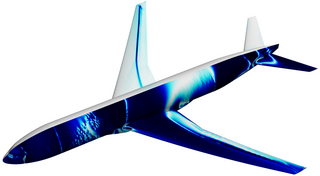

In fluid dynamics, turbulence modeling is the construction and use of a mathematical model to predict the effects of turbulence. Turbulent flows are commonplace in most real-life scenarios. In spite of decades of research, there is no analytical theory to predict the evolution of these turbulent flows. The equations governing turbulent flows can only be solved directly for simple cases of flow. For most real-life turbulent flows, CFD simulations use turbulent models to predict the evolution of turbulence. These turbulence models are simplified constitutive equations that predict the statistical evolution of turbulent flows.

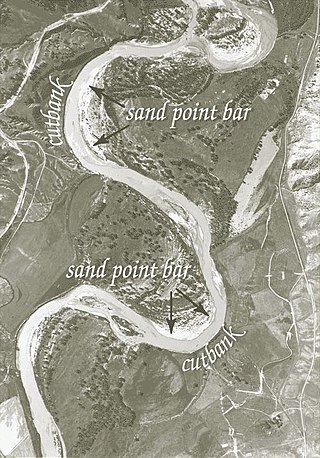

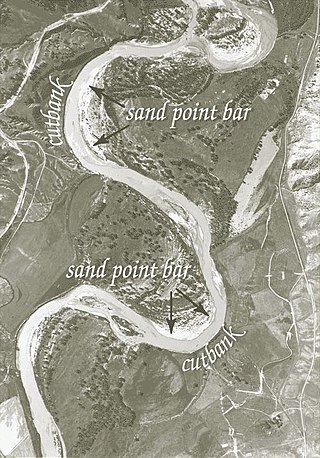

A meander is one of a series of regular sinuous curves in the channel of a river or other watercourse. It is produced as a watercourse erodes the sediments of an outer, concave bank and deposits sediments on an inner, convex bank which is typically a point bar. The result of this coupled erosion and sedimentation is the formation of a sinuous course as the channel migrates back and forth across the axis of a floodplain.

Marshall Nicholas Rosenbluth was an American plasma physicist and member of the National Academy of Sciences, and member of the American Philosophical Society. In 1997 he was awarded the National Medal of Science for discoveries in controlled thermonuclear fusion, contributions to plasma physics, and work in computational statistical mechanics. He was also a recipient of the E.O. Lawrence Prize (1964), the Albert Einstein Award (1967), the James Clerk Maxwell Prize for Plasma Physics (1976), the Enrico Fermi Award (1985), and the Hannes Alfvén Prize (2002).

Carl Wilhelm Oseen was a theoretical physicist in Uppsala and Director of the Nobel Institute for Theoretical Physics in Stockholm.

In geography, the Baer–Babinet law, sometimes called Baer's law, identifies a way in which the process of formation of rivers is influenced by the rotation of the Earth. According to the hypothesis, because of the rotation of the Earth, erosion occurs mostly on the right banks of rivers in the Northern Hemisphere, and in the Southern Hemisphere on the left banks.

A point bar is a depositional feature made of alluvium that accumulates on the inside bend of streams and rivers below the slip-off slope. Point bars are found in abundance in mature or meandering streams. They are crescent-shaped and located on the inside of a stream bend, being very similar to, though often smaller than, towheads, or river islands.

In fluid dynamics, flow can be decomposed into primary flow plus secondary flow, a relatively weaker flow pattern superimposed on the stronger primary flow pattern. The primary flow is often chosen to be an exact solution to simplified or approximated governing equations, such as potential flow around a wing or geostrophic current or wind on the rotating Earth. In that case, the secondary flow usefully spotlights the effects of complicated real-world terms neglected in those approximated equations. For instance, the consequences of viscosity are spotlighted by secondary flow in the viscous boundary layer, resolving the tea leaf paradox. As another example, if the primary flow is taken to be a balanced flow approximation with net force equated to zero, then the secondary circulation helps spotlight acceleration due to the mild imbalance of forces. A smallness assumption about secondary flow also facilitates linearization.

Robert Harry Kraichnan, a resident of Santa Fe, New Mexico, was an American theoretical physicist best known for his work on the theory of fluid turbulence.

Plasma actuators are a type of actuator currently being developed for aerodynamic flow control. Plasma actuators impart force in a similar way to ionocraft. Plasma flows control has drawn considerable attention and been used in boundary layer acceleration, airfoil separation control, forebody separation control, turbine blade separation control, axial compressor stability extension, heat transfer and high-speed jet control.

A meander cutoff is a natural form of a cutting or cut in a river occurs when a pronounced meander (hook) in a river is breached by a flow that connects the two closest parts of the hook to form a new channel, a full loop. The steeper drop in gradient (slope) causes the river flow gradually to abandon the meander which will silt up with sediment from deposition. Cutoffs are a natural part of the evolution of a meandering river. Rivers form meanders as they flow laterally downstream, see sinuosity.

Subhasish Dey is a hydraulician and educator. He is known for his research on the hydrodynamics and acclaimed for his contributions in developing theories and solution methodologies of various problems on hydrodynamics, turbulence, boundary layer, sediment transport and open channel flow. He is currently a distinguished professor of Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur (2023–). Before, he worked as a professor of the department of civil engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur (1998–2023), where he served as the head of the department during 2013–15 and held the position of Brahmaputra Chair Professor during 2009–14 and 2015. He also held the adjunct professor position in the Physics and Applied Mathematics Unit at Indian Statistical Institute Kolkata during 2014–19. Besides he has been named a distinguished visiting professor at the Tsinghua University in Beijing, China.

This timeline describes the major developments, both experimental and theoretical understanding of fluid mechanics and continuum mechanics. This timeline includes developments in: