| The Cherokee Tobacco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 20,April 10–11, 1871 Decided May 1, 1871 | |

| Full case name | The Cherokee Tobacco |

| Citations | 78 U.S. 616 ( more ) |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Swayne, joined by Clifford, Miller, Strong |

| Dissent | Bradley, joined by Davis |

| Chase, Nelson, and Field took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

The Cherokee Tobacco Case, 78 U.S. (11 Wall.) 616 (1870), is a United States court case with implications relating to tribal sovereignty in the United States.

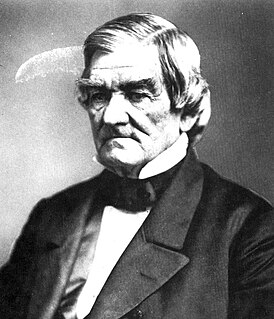

Two Cherokee men, Elias C. Boudinot and Stand Watie, refused to pay taxes on tobacco manufactured in the Cherokee Nation, as required by the Internal Revenue Act 1868. They argued that they were exempt from paying the taxes by the Cherokee Treaty of 1866. The Supreme Court decided against the men, stating that a law of Congress can supersede the provisions of a treaty. [1]

Boudinot and Watie, with the help of attorneys A. Pike, R. W. Johnson, and B.F. Butler, [2] argued that they were exempt from paying the tax on the tobacco. They used the argument that Article 10 of the Treaty of 1866 with the Cherokee Nation stated,

“Every Cherokee and freed person resident in the Cherokee nation shall have the right to sell any products of his farm, including his or her live stock or any merchandise or manufactured products, and to ship and drive the same to market without restraint, paying any tax thereon which is now or may be levied by the United States on the quantity sold outside of the Indian Territory.”

They used this part because to them it meant that any Cherokee and freed person living in Cherokee Nation had the right to do whatever they wished with their products of their farms and had the right to do so without being taxed. On the other hand, Amos Akerman, U.S. Attorney General, and Benjamin Bristow, Solicitor General, on behalf of the United States, argued that, the 107th section of the Internal Revenue Act of July 20, 1868, states that,

"The internal revenue laws imposing taxes on distilled spirits, fermented liquors, tobacco, snuff, and cigars, shall be construed to extend to such articles produced anywhere within the exterior boundaries of the United States, whether the same shall be within a collection district or not,"

In other words that under the Internal Revenue Act of 1868, the United States had the right to tax anyone within the countries boundaries as well as within the exterior boundaries. Also because this act was passed two years after the Cherokee Nation Treaty, it overruled any previous acts.

Justice Swayne wrote the decision in this case for a deeply fractured Court; three justices concurred with Swayne, two dissented and three did not participate. Swayne indicated the legal direction he was heading by noting at the outset of the opinion that the case involved, “first the question of the intention of Congress, and second, assuming the intention to exist, the question of its power, to tax certain tobacco in the Territory of the Cherokee nation in the face of a prior treaty between that nation and the United States that such tobacco should be exempt from taxation.” [2] His decision yielded one of the most problematic and ambiguous doctrines in Indian law- whether tribes, as preexisting entities, may be included or excluded under the scope of general laws enacted by Congress. The documentary evidence-including the preexisting political status of tribes, prior Supreme Court precedent, the treaty relationship, and the constitutional clauses acknowledging the distinctive status of tribal polities- clearly support exclusion. Indian territories, in other words, were not regarded as included in congressional enactments unless the tribe had given its explicit consent and unless they were expressly included in the law.

The Cherokee Tobacco case, however, created a new interpretation- that general congressional acts do apply to tribes unless Congress explicitly excludes them. Thus, Boudinot and Watie were required to pay the tax on the tobacco. [3] This decision not only affected these two men, but it also affected every decision that gave weight to the idea that Indian Nations were sovereign nations. With this decision, people would argue that if countries outside the United States, sovereign countries, were not required to pay taxes to the United States then how was a nation within its borders required to pay taxes and still be a sovereign nation. The holding in this case was a huge blow to the fight for Indian sovereignty.