European Union competition law is the competition law in use within the European Union. It promotes the maintenance of competition within the European Single Market by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies to ensure that they do not create cartels and monopolies that would damage the interests of society.

The rule of reason is a legal doctrine used to interpret the Sherman Antitrust Act, one of the cornerstones of United States antitrust law. While some actions like price-fixing are considered illegal per se, other actions, such as possession of a monopoly, must be analyzed under the rule of reason and are only considered illegal when their effect is to unreasonablyrestrain trade. William Howard Taft, then Chief Judge of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, first developed the doctrine in a ruling on Addyston Pipe and Steel Co. v. United States, which was affirmed in 1899 by the Supreme Court. The doctrine also played a major role in the 1911 Supreme Court case Standard Oil Company of New Jersey v. United States.

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust law, anti-monopoly law, and trade practices law; the act of pushing for antitrust measures or attacking monopolistic companies is commonly known as trust busting.

Resale price maintenance (RPM) or, occasionally, retail price maintenance is the practice whereby a manufacturer and its distributors agree that the distributors will sell the manufacturer's product at certain prices, at or above a price floor or at or below a price ceiling. If a reseller refuses to maintain prices, either openly or covertly, the manufacturer may stop doing business with it. Resale price maintenance is illegal in many jurisdictions.

The European single market, also known as the European internal market or the European common market, is the single market comprising mainly the 27 member states of the European Union (EU). With certain exceptions, it also comprises Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway and Switzerland. The single market seeks to guarantee the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people, known collectively as the "four freedoms". This is achieved through common rules and standards that all participating states are legally committed to follow.

The Competition Act 1998 is the current major source of competition law in the United Kingdom, along with the Enterprise Act 2002. The act provides an updated framework for identifying and dealing with restrictive business practices and abuse of a dominant market position.

European Union merger law is a part of the law of the European Union. It is charged with regulating mergers between two or more entities in a corporate structure. This institution has jurisdiction over concentrations that might or might not impede competition. Although mergers must comply with policies and regulations set by the commission; certain mergers are exempt if they promote consumer welfare. Mergers that fail to comply with the common market may be blocked. It is part of competition law and is designed to ensure that firms do not acquire such a degree of market power on the free market so as to harm the interests of consumers, the economy and society as a whole. Specifically, the level of control may lead to higher prices, less innovation and production.

Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits cartels and other agreements that could disrupt free competition in the European Economic Area's internal market.

Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is aimed at preventing businesses in an industry from abusing their positions by colluding to fix prices or taking action to prevent new businesses from gaining a foothold in the industry. Its core role is the regulation of monopolies, which restrict competition in private industry and produce worse outcomes for consumers and society. It is the second key provision, after Article 101, in European Union (EU) competition law.

The history of competition law refers to attempts by governments to regulate competitive markets for goods and services, leading up to the modern competition or antitrust laws around the world today. The earliest records traces back to the efforts of Roman legislators to control price fluctuations and unfair trade practices. Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, kings and queens repeatedly cracked down on monopolies, including those created through state legislation. The English common law doctrine of restraint of trade became the precursor to modern competition law. This grew out of the codifications of United States antitrust statutes, which in turn had considerable influence on the development of European Community competition laws after the Second World War. Increasingly, the focus has moved to international competition enforcement in a globalised economy.

United Kingdom competition law is affected by both British and European elements. The Competition Act 1998 and the Enterprise Act 2002 are the most important statutes for cases with a purely national dimension. However, if the effect of a business' conduct would reach across borders, the European Commission has competence to deal with the problems, and exclusively EU law would apply. Even so, the section 60 of the Competition Act 1998 provides that UK rules are to be applied in line with European jurisprudence. Like all competition law, that in the UK has three main tasks.

Procureur du Roi v Benoît and Gustave Dassonville (1974) Case 8/74 is an EU law case of the European Court of Justice, in which a 'distinctly applicable measure of equivalent effect' to a quantitative restriction of trade in the European Union was held to exist on a Scotch whisky imported from France.

Commission v Anic Partecipazioni SpA (1999) C-49/92 is an EU competition law case, concerning the requirements for finding that there has been a cartel, or unlawful collusion, within TFEU article 101.

Consten SaRL and Grundig GmbH v Commission (1966) Case 56/64 is an EU competition law case, concerning vertical anti-competitive agreements.

GlaxoSmithKline Services Unlimited v Commission (2009) C-513/06 is an EU competition law case, concerning the meaning of harm to "competition" under TFEU article 101.

O2 (Germany) GmbH & Co OHG v Commission (2006) T-328/03 is an EU competition law case, concerning the requirements for a restriction of competition to be found under TFEU article 101.

Albany International BV v Stichting Bedrijfspensioenfonds Textielindustrie (1999) C-67/96 is an EU law case, concerning the boundary between European labour law and European competition law in the European Union.

Opinion 2/13 (2014) is an EU law case determined by the European Court of Justice, concerning the accession of the European Union to the European Convention on Human Rights, and more generally the relationship between the European Court of Justice and European Court of Human Rights.

Mergers in United Kingdom law is a theory-based regulation that helps forecast and avoid abuse, while indirectly maintaining a competitive framework within the market. A true merger is one in which two separate entities merge into an entirely new entity. In Law the term ‘merger’ has a much broader application, for example where A acquires all, or a majority of, the shares in B, and is able to control the affairs of B as such.

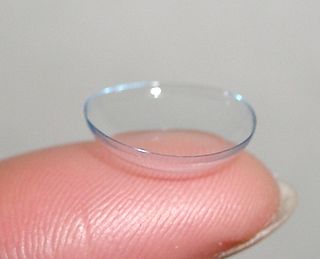

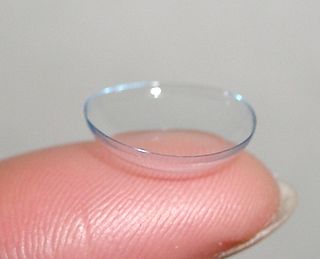

Ker-Optika bt v ÀNTSZ Dél-dunántúli Regionális Intézete [2010] ECR, Case C-108/09 is an EU law case concerning a conflict of law between Hungarian national legislation and European Union law. The Hungarian legislation regarding the online sale of contact lenses was considered with regards to whether it was necessary for the protection of public health, and it was concluded that this could have been done by less restrictive measures. Despite the internal measure in this case being categorised as a selling arrangement, which would generally be determined by the discrimination test established in Keck, the Court went on to use a market access test, as per Italian Trailers. Thus, this case is crucial in the recent development of the tests for determining measures equaling equivalent effect.