Related Research Articles

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid, which in turn runs through steam turbines. These either drive a ship's propellers or turn electrical generators' shafts. Nuclear generated steam in principle can be used for industrial process heat or for district heating. Some reactors are used to produce isotopes for medical and industrial use, or for production of weapons-grade plutonium. As of 2022, the International Atomic Energy Agency reports there are 422 nuclear power reactors and 223 nuclear research reactors in operation around the world.

A pressurized water reactor (PWR) is a type of light-water nuclear reactor. PWRs constitute the large majority of the world's nuclear power plants. In a PWR, the primary coolant (water) is pumped under high pressure to the reactor core where it is heated by the energy released by the fission of atoms. The heated, high pressure water then flows to a steam generator, where it transfers its thermal energy to lower pressure water of a secondary system where steam is generated. The steam then drives turbines, which spin an electric generator. In contrast to a boiling water reactor (BWR), pressure in the primary coolant loop prevents the water from boiling within the reactor. All light-water reactors use ordinary water as both coolant and neutron moderator. Most use anywhere from two to four vertically mounted steam generators; VVER reactors use horizontal steam generators.

A nuclear meltdown is a severe nuclear reactor accident that results in core damage from overheating. The term nuclear meltdown is not officially defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency or by the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. It has been defined to mean the accidental melting of the core of a nuclear reactor, however, and is in common usage a reference to the core's either complete or partial collapse.

In nuclear engineering, a neutron moderator is a medium that reduces the speed of fast neutrons, ideally without capturing any, leaving them as thermal neutrons with only minimal (thermal) kinetic energy. These thermal neutrons are immensely more susceptible than fast neutrons to propagate a nuclear chain reaction of uranium-235 or other fissile isotope by colliding with their atomic nucleus.

The RBMK is a class of graphite-moderated nuclear power reactor designed and built by the Soviet Union. It is one of two reactor types to be developed in the Soviet Union in the 1970s. The name refers to its (unusual) design where, instead of a large steel pressure vessel surrounding the entire core, the core is surrounded by a cylindrical annular steel tank inside a concrete vault and each fuel assembly is enclosed in an individual 8 cm (inner) diameter pipe. The channels also contain the coolant, and are surrounded by graphite.

A scram or SCRAM is an emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor effected by immediately terminating the fission reaction. It is also the name that is given to the manually operated kill switch that initiates the shutdown. In commercial reactor operations, this type of shutdown is often referred to as a "scram" at boiling water reactors (BWR), a "reactor trip" at pressurized water reactors and EPIS at a CANDU reactor. In many cases, a scram is part of the routine shutdown procedure, which serves to test the emergency shutdown system.

A fast-neutron reactor (FNR) or fast-spectrum reactor or simply a fast reactor is a category of nuclear reactor in which the fission chain reaction is sustained by fast neutrons, as opposed to slow thermal neutrons used in thermal-neutron reactors. Such a fast reactor needs no neutron moderator, but requires fuel that is relatively rich in fissile material when compared to that required for a thermal-neutron reactor. Around 20 land based fast reactors have been built, accumulating over 400 reactor years of operation globally. The largest of this was the Superphénix Sodium cooled fast reactor in France that was designed to deliver 1,242 MWe. Fast reactors have been intensely studied since the 1950s, as they provide certain advantages over the existing fleet of water cooled and water moderated reactors. These are:

A loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA) is a mode of failure for a nuclear reactor; if not managed effectively, the results of a LOCA could result in reactor core damage. Each nuclear plant's emergency core cooling system (ECCS) exists specifically to deal with a LOCA.

The light-water reactor (LWR) is a type of thermal-neutron reactor that uses normal water, as opposed to heavy water, as both its coolant and neutron moderator; furthermore a solid form of fissile elements is used as fuel. Thermal-neutron reactors are the most common type of nuclear reactor, and light-water reactors are the most common type of thermal-neutron reactor.

Passive nuclear safety is a design approach for safety features, implemented in a nuclear reactor, that does not require any active intervention on the part of the operator or electrical/electronic feedback in order to bring the reactor to a safe shutdown state, in the event of a particular type of emergency. Such design features tend to rely on the engineering of components such that their predicted behaviour would slow down, rather than accelerate the deterioration of the reactor state; they typically take advantage of natural forces or phenomena such as gravity, buoyancy, pressure differences, conduction or natural heat convection to accomplish safety functions without requiring an active power source. Many older common reactor designs use passive safety systems to a limited extent, rather, relying on active safety systems such as diesel-powered motors. Some newer reactor designs feature more passive systems; the motivation being that they are highly reliable and reduce the cost associated with the installation and maintenance of systems that would otherwise require multiple trains of equipment and redundant safety class power supplies in order to achieve the same level of reliability. However, weak driving forces that power many passive safety features can pose significant challenges to effectiveness of a passive system, particularly in the short term following an accident.

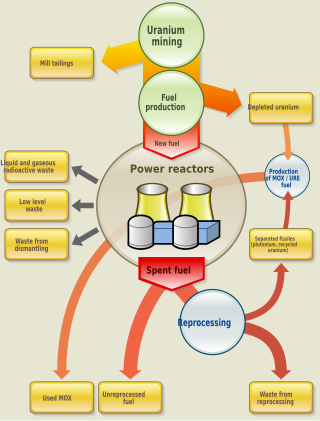

Nuclear fuel is material used in nuclear power stations to produce heat to power turbines. Heat is created when nuclear fuel undergoes nuclear fission.

A reactor pressure vessel (RPV) in a nuclear power plant is the pressure vessel containing the nuclear reactor coolant, core shroud, and the reactor core.

The supercritical water reactor (SCWR) is a concept Generation IV reactor, designed as a light water reactor (LWR) that operates at supercritical pressure. The term critical in this context refers to the critical point of water, and should not be confused with the concept of criticality of the nuclear reactor.

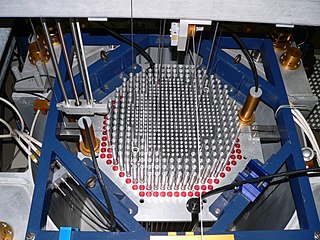

A nuclear reactor core is the portion of a nuclear reactor containing the nuclear fuel components where the nuclear reactions take place and the heat is generated. Typically, the fuel will be low-enriched uranium contained in thousands of individual fuel pins. The core also contains structural components, the means to both moderate the neutrons and control the reaction, and the means to transfer the heat from the fuel to where it is required, outside the core.

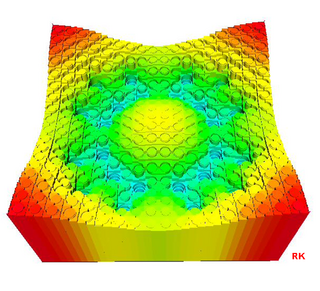

Nuclear reactor physics is the field of physics that studies and deals with the applied study and engineering applications of chain reaction to induce a controlled rate of fission in a nuclear reactor for the production of energy. Most nuclear reactors use a chain reaction to induce a controlled rate of nuclear fission in fissile material, releasing both energy and free neutrons. A reactor consists of an assembly of nuclear fuel, usually surrounded by a neutron moderator such as regular water, heavy water, graphite, or zirconium hydride, and fitted with mechanisms such as control rods which control the rate of the reaction.

In applications such as nuclear reactors, a neutron poison is a substance with a large neutron absorption cross-section. In such applications, absorbing neutrons is normally an undesirable effect. However, neutron-absorbing materials, also called poisons, are intentionally inserted into some types of reactors in order to lower the high reactivity of their initial fresh fuel load. Some of these poisons deplete as they absorb neutrons during reactor operation, while others remain relatively constant.

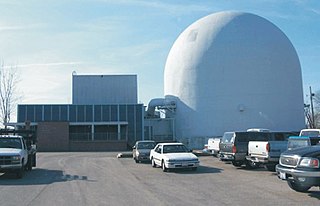

The Whiteshell Reactor No. 1, or WR-1, was a Canadian research reactor located at AECL's Whiteshell Laboratories (WNRL) in Manitoba. Originally known as Organic-Cooled Deuterium-Reactor Experiment (OCDRE), it was built to test the concept of a CANDU-type reactor that replaced the heavy water coolant with an oil substance. This had a number of potential advantages in terms of cost and efficiency.

A pressurized heavy-water reactor (PHWR) is a nuclear reactor that uses heavy water (deuterium oxide D2O) as its coolant and neutron moderator. PHWRs frequently use natural uranium as fuel, but sometimes also use very low enriched uranium. The heavy water coolant is kept under pressure to avoid boiling, allowing it to reach higher temperature (mostly) without forming steam bubbles, exactly as for a pressurized water reactor. While heavy water is very expensive to isolate from ordinary water (often referred to as light water in contrast to heavy water), its low absorption of neutrons greatly increases the neutron economy of the reactor, avoiding the need for enriched fuel. The high cost of the heavy water is offset by the lowered cost of using natural uranium and/or alternative fuel cycles. As of the beginning of 2001, 31 PHWRs were in operation, having a total capacity of 16.5 GW(e), representing roughly 7.76% by number and 4.7% by generating capacity of all current operating reactors.

An organic nuclear reactor, or organic cooled reactor (OCR), is a type of nuclear reactor that uses some form of organic fluid, typically a hydrocarbon substance like polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), for cooling and sometimes as a neutron moderator as well.

The Chernobyl disaster was a catastrophic nuclear disaster that occurred in the early hours of 26 April 1986, at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Soviet Ukraine. The accident occurred when Reactor Number 4 exploded and destroyed most of the reactor building, spreading debris and radioactive material across the surrounding area, and over the following days and weeks, most of mainland Europe was contaminated with radionuclides that emitted dangerous amounts of ionizing radiation. To investigate the causes of the accident, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) used its organization, the International Nuclear Safety Advisory Group (INSAG).

References

- Chernobyl - A Canadian Perspective - A brochure describing nuclear reactors in general and the RBMK design in particular, focusing on the safety differences between them and CANDU reactors. Published by Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. (AECL), designer of the CANDU reactor.

- J.J. Whitlock, Why do CANDU reactors have a "positive void coefficient"? - An explanation published on The Canadian Nuclear FAQ, a website of "frequently-asked questions" and answers about Canadian nuclear technology.

- J.J. Whitlock, How do CANDU reactors meet high safety standards, despite having a "positive void coefficient"? - An explanation published on The Canadian Nuclear FAQ, a website of "frequently-asked questions" and answers about Canadian nuclear technology.