A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some have hook and ring closures and a few have mortice and tenon locking catches to close them. Many seem designed for near-permanent wear and would have been difficult to remove.

The Demetae were a Celtic people of Iron Age and Roman period, who inhabited modern Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire in south-west Wales. The tribe also gave their name to the medieval Kingdom of Dyfed, the modern area and county of Dyfed and the distinct dialect of Welsh spoken in modern south-west Wales, Dyfedeg.

Dolgellau is a town and community in Gwynedd, north-west Wales, lying on the River Wnion, a tributary of the River Mawddach. It was the traditional county town of the historic county of Merionethshire until the county of Gwynedd was created in 1974. Dolgellau is the main base for climbers of Cadair Idris and Mynydd Moel which are visible from the town. Dolgellau is the second largest settlement in southern Gwynedd after Tywyn and includes the community of Penmaenpool.

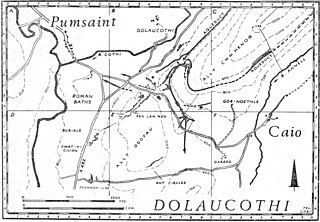

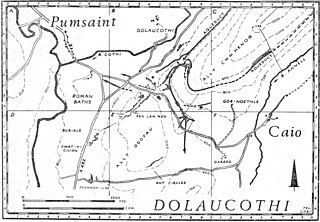

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines, also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mines are located within the Dolaucothi Estate, which is owned by the National Trust.

Gwynfynydd Gold Mine is near Ganllwyd, Dolgellau, Gwynedd, Wales. The lode, which was discovered in 1860, was worked from 1884. It has produced more than 45,000 troy ounces of Welsh gold until mining ceased in 1998. The equivalent of 1,400 kg.

The ClogauGold Mine is a gold mine near Bontddu in North Wales.

Pumsaint is a village in Carmarthenshire, Wales, halfway between Llanwrda and Lampeter on the A482 in the valley of the Afon Cothi. It forms part of the extensive estate of Dolaucothi, which is owned by the National Trust.

Bontddu is a small settlement just east of Barmouth, near the town of Dolgellau in Gwynedd, Wales. It is in the community of Llanelltyd.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

The Glyndŵr Award is made for an outstanding contribution to the arts in Wales. It is given by the Machynlleth Tabernacle Trust to pre-eminent figures in music, art and literature in rotation. The award takes its name after Owain Glyndŵr, crowned Prince of Wales at Machynlleth in 1404.

Sarn Helen refers to several stretches of Roman road in Wales. The 160-mile (260 km) route, which follows a meandering course through central Wales, connects Aberconwy in the north with Carmarthen in the west. Despite its length, academic debate continues as to the precise course of the Roman road. Many sections are now used by the modern road network while other parts are still traceable. However, there are sizeable stretches that have been lost and are unidentifiable.

Luentinum or Loventium refers to the Roman fort at Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire. The 1.9 hectares site lies either side of the A482 in Pumsaint and was in use from the mid 70s AD to around 120 AD. It may have had particular functions associated with the adjacent Dolaucothi Gold Mines. It formed part of a network of at least 30 forts across Wales, such as Llandovery, Bremia/Llanio near Llanddewi Brefi, and the fort at Llandeilo. The Roman road Sarn Helen, which runs past the Llanio and Llandovery forts was nearby.

Mining was one of the most prosperous activities in Roman Britain. Britain was rich in resources such as copper, gold, iron, lead, salt, silver, and tin, materials in high demand in the Roman Empire. Sufficient supply of metals was needed to fulfil the demand for coinage and luxury artefacts by the elite. The Romans started panning and puddling for gold. The abundance of mineral resources in the British Isles was probably one of the reasons for the Roman conquest of Britain. They were able to use advanced technology to find, develop and extract valuable minerals on a scale unequaled until the Middle Ages.

Mining in Wales provided a significant source of income to the economy of Wales throughout the nineteenth century and early to mid twentieth century. It was key to the Industrial Revolution in Wales, and to the whole of Great Britain.

Frequently used in mines and probably elsewhere, the reverse overshot water wheel was a Roman innovation to help remove water from the lowest levels of underground workings. It is described by Vitruvius in his work De architectura published circa 25 BC. The remains of such systems found in Roman mines by later mining operations show that they were used in sequences so as to lift water a considerable height.

Fire-setting is a method of traditional mining used most commonly from prehistoric times up to the Middle Ages. Fires were set against a rock face to heat the stone, which was then doused with liquid, causing the stone to fracture by thermal shock. Rapid heating causes thermal shock by itself—without subsequent cooling—by producing different degrees of expansion in different parts of the rock. In practice, rapid cooling may or may not have been helpful to produce the desired effect. Some experiments have suggested that the water did not have a noticeable effect on the rock, but rather helped the miners' progress by quickly cooling down the area after the fire. This technique was best performed in opencast mines where the smoke and fumes could dissipate safely. The technique was very dangerous in underground workings without adequate ventilation. The method became largely redundant with the growth in use of explosives.

Hushing is an ancient and historic mining method using a flood or torrent of water to reveal mineral veins. The method was applied in several ways, both in prospecting for ores, and for their exploitation. Mineral veins are often hidden below soil and sub-soil, which must be stripped away to discover the ore veins. A flood of water is very effective in moving soil as well as working the ore deposits when combined with other methods such as fire-setting.

The Dolaucothi Estate is situated about 1 mile (1.6 km) north-west of the village of Caio up the Cothi Valley in the community of Cynwyl Gaeo, in Carmarthenshire, Wales. Dolaucothi means ‘the meadows of the Cothi’.

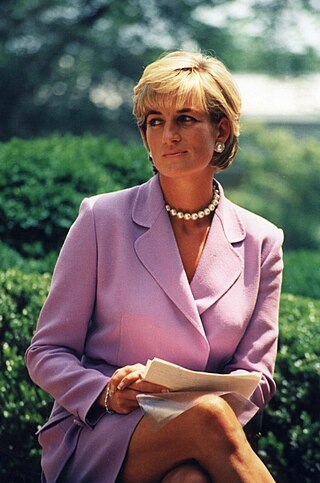

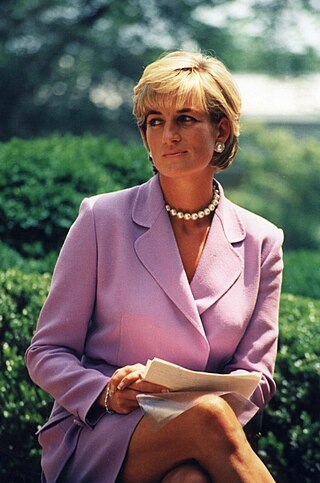

Diana, Princess of Wales, owned a collection of jewels both as a member of the British royal family and as a private individual. These were separate from the coronation and state regalia of the crown jewels. Most of her jewels were either presents from foreign royalty, on loan from Queen Elizabeth II, wedding presents, purchased by Diana herself, or heirlooms belonging to the Spencer family.

The Industrial Revolution in Wales was the adoption and developments of new technologies in Wales in the 18th and 19th centuries as part of the Industrial Revolution, resulting in increases in the scale of industry in Wales.