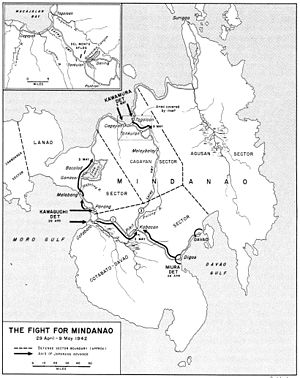

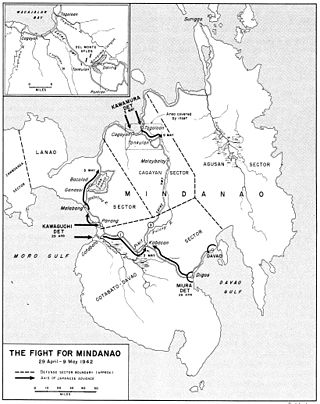

On the afternoon of 2 May, the 102nd Division was alerted for combat after the convoy carrying the Kawamura Detachment, the Japanese invasion force for the Cagayan Sector, was spotted by a reconnaissance aircraft north of Macajalar Bay. The convoy entered the bay during the night, precipitating execution of the previously prepared demolition plan. The Japanese began simultaneous landings at Cagayan and at Tagoloan about 01:00 on 3 May, supported by the fire of two destroyers from the convoy. By dawn, the Japanese firmly held the shoreline between Tagoloan and the Sayre Highway. Although Webb was unable to prevent the Cagayan landing, he launched a two-company counterattack against the beachhead. In his subsequent report to Sharp, Webb stated that he might have been able to repulse the Japanese if he had not been forced to retreat when his right flank was exposed by the retreat of the 61st Field Artillery.

Battle of Mangima Canyon

In response to the Japanese landing, Sharp moved his reserves, which were the 2.95-inch gun detachment of Major Paul D. Phillips, the 62nd Infantry of Lieutenant Colonel Allen Thayer, and the 93rd Infantry of Major John C. Goldtrap, forward. The 2.95-inch gun detachment and the 93rd Infantry took up blocking positions on the Sayre Highway in the evening, as the 62nd Infantry moved up behind them. At 16:00 Morse ordered a general withdrawal, under the cover of darkness, to positions astride the highway about six miles south of the beach, but this was never effected due to a conference between Sharp, Morse, Woodbridge, and Webb. Instead, the commanders decided to defend along a line parallel to the Mangima Canyon and River east of Tankulan, where the Sayre Highway briefly separated into an upper and lower road, in order to block the Sayre Highway and prevent a Japanese advance into central Mindanao.

Sharp issued his orders for the withdrawal at 23:00. The Dalirig Sector on the upper (northern) road was held by the 102nd Division with the 62nd Infantry, 81st Field Artillery, the 2.95-inch gun detachment, and Companies C and E of the 43rd Infantry (PS), under Morse's command. The former commander of the Mindanao Force Reserve, Colonel William F. Dalton, took command of the Puntian Sector on the lower (southern road) with the 61st Field Artillery and the 93rd Infantry. Separated by the Japanese advance, the 103rd Infantry was made independent, tasked with defending the Cagayan River valley.

All units reached the positions by the morning of 4 May, taking advantage of a lull in the Japanese advance to organize the line for the rest of that day and the next. The division's 62nd Infantry held the main line of resistance along the east wall of Mangima Canyon, closely supported by the 2.95-inch gun detachment, while the reserve, Companies C and E of the 43rd Infantry (PS), was stationed in Dalirig itself. The remnants of the 81st Field Artillery, reduced to 200 men, were stationed in a draw 500 yards behind the town.

The Kawamura Detachment resumed its advance on 6 May, reaching Tankulan by the end of the day and registering artillery on Dalirig. On the next day, accurate Japanese artillery fire and air attack targeted the 62nd Infantry, whose left battalion suffered the most, forcing Thayer to reinforce the line with his reserve battalion. The bombardment continued until 19:00 on 8 May, when the Japanese infiltrated the division's lines, sowing disorder. In the chaos two platoons "mysteriously received orders to withdraw" and retreated, but were quickly stopped as no such orders had actually been issued. Before they could return to the front they came under attack from a small force of Japanese infiltrators, after which other Filipino troops commenced firing, although they could not distinguish between friend and foe in the night, inducing further panic on the line. The firing was only halted after Thayer's personal intervention.

After holding through the night, the 62nd Infantry, "tired and disorganized", retreated towards Dalirig by the morning of 9 May. The 2.5-inch gun detachment retreated, leaving the two Philippine Scout companies as the last organized resistance in the sector. At 11:30, as the 62nd retreated through the town, the Japanese attacked them on three sides, turning the retreat into a rout. The two Scout companies held their positions, but were forced to withdraw when threatened with encirclement. The Dalirig forces fled over exposed terrain, discarding equipment as they progressed under small arms, artillery fire, and strafing. By the end of the 9 May the Dalirig Sector forces no longer existed, except for the 150 men of the 2.5-inch gun detachment, holding positions five miles to the east of the town.