Related Research Articles

James Monroe, a Founding Father of the United States, served as its fifth president from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as president as well as the last president of the Virginia dynasty. He was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, and his presidency coincided with the Era of Good Feelings, concluding the First Party System era of American politics. He issued the Monroe Doctrine, a policy of limiting European colonialism in the Americas. Monroe previously served as governor of Virginia, a member of the United States Senate, U.S. ambassador to France and Britain, the seventh secretary of state, and the eighth secretary of war.

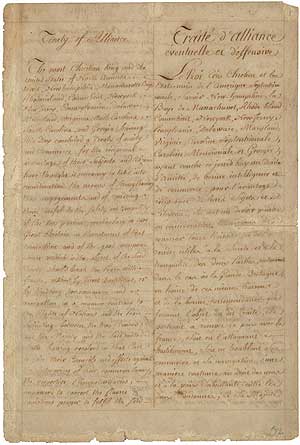

The Treaty of Alliance, also known as the Franco-American Treaty, was a defensive alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States formed amid the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain. It was signed by delegates of King Louis XVI and the Second Continental Congress in Paris on February 6, 1778, along with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and a secret clause providing for the entry of other European allies; together these instruments are sometimes known as the Franco-American Alliance or the Treaties of Alliance. The agreements marked the official entry of the United States on the world stage, and formalized French recognition and support of U.S. independence that was to be decisive in America's victory.

The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty, was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined the boundary between the U.S. and Mexico. It settled a standing border dispute between the two countries and was considered a triumph of American diplomacy. It came during the successful Spanish American wars of independence against Spain.

The Platt Amendment was a piece of United States legislation enacted as part of the Army Appropriations Act of 1901 that defined the relationship between the United States and Cuba following the Spanish-American War. It stipulated seven conditions for the withdrawal of United States troops remaining in Cuba at the end of the Spanish–American War, and an eighth condition that Cuba sign a treaty accepting these seven conditions. It helped define the terms of Cuba-United States relations.

The Republic of Texas was annexed into the United States and admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Torrijos–Carter Treaties are two treaties signed by the United States and Panama in Washington, D.C., on September 7, 1977, which superseded the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1903. The treaties guaranteed that Panama would gain control of the Panama Canal after 1999, ending the control of the canal that the U.S. had exercised since 1903. The treaties are named after the two signatories, U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the Commander of Panama's National Guard, General Omar Torrijos.

Pan-Americanism is a movement that seeks to create, encourage, and organize relationships, an association, and cooperation among the states of the Americas, through diplomatic, political, economic, and social means. The term Pan-Americanism was first used by the New York Evening Post in 1882 when referring to James G. Blaine’s proposal for a conference of American states in Washington D.C., gaining more popularity after the first conference in 1889. Through international conferences, Pan-Americanism embodies the spirit of cooperation to create and ratify treaties for the betterment in the Americas. Since 1826, the Americas have evolved the international conferences from an idea of revolutionary Simon Bolivar to the creation of an inter-America organization with the founding of the Organization of American States.

The Lodge Reservations, written by United States Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, the Republican Majority Leader and Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations, were fourteen reservations to the Treaty of Versailles and other proposed post-war agreements. The Treaty called for the creation of a League of Nations in which the promise of mutual security would hopefully prevent another major world war; the League charter, primarily written by President Woodrow Wilson, let the League set the terms for war and peace. If the League called for military action, all members would have to join in.

The separation of Panama from Colombia was formalized on 3 November 1903, with the establishment of the Republic of Panama and the abolition of the Colombia-Costa Rica border. From the Independence of Panama from Spain in 1821, Panama had simultaneously declared independence from Spain and joined itself to the confederation of Gran Colombia through the Independence Act of Panama. Panama was always tenuously connected to the rest of the country to the south, owing to its remoteness from the government in Bogotá and lack of a practical overland connection to the rest of Gran Colombia. In 1840–41, a short-lived independent republic was established under Tomás de Herrera. After rejoining Colombia following a 13-month independence, it remained a province which saw frequent rebellious flare-ups, notably the Panama crisis of 1885, which saw the intervention of the United States Navy, and a reaction by the Chilean Navy.

The presidency of James Monroe began on March 4, 1817, when James Monroe was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1825. Monroe, the fifth United States president, took office after winning the 1816 presidential election by an overwhelming margin over Federalist Rufus King. This election was the last in which the Federalists fielded a presidential candidate, and Monroe was unopposed in the 1820 presidential election. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was succeeded by his Secretary of State John Quincy Adams.

Panama is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America.

Diplomacy was central to the outcome of the American Revolutionary War and the broader American Revolution. Before the outbreak of armed conflict in April 1775, the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain had initially sought to resolve their disputes peacefully from within the British political system. Once open hostilities began, the war developed an international dimension, as both sides engaged in foreign diplomacy to further their goals, while governments and nations worldwide took interest in the geopolitical and ideological implications of the conflict.

The Franco-American alliance was the 1778 alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States during the American Revolutionary War. Formalized in the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, it was a military pact in which the French provided many supplies for the Americans. The Netherlands and Spain later joined as allies of France; Britain had no European allies. The French alliance was possible once the Americans captured a British invasion army at Saratoga in October 1777, demonstrating the viability of the American cause. The alliance became controversial after 1793 when Great Britain and Revolutionary France again went to war and the U.S. declared itself neutral. Relations between France and the United States worsened as the latter became closer to Britain in the Jay Treaty of 1795, leading to an undeclared Quasi War. The alliance was defunct by 1794 and formally ended in 1800.

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1801 to 1829 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the presidential administrations of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams. International affairs in the first half of this period were dominated by the Napoleonic Wars, which the United States became involved with in various ways, including the War of 1812. The period saw the U.S. double in size, gaining control of Florida and lands between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. The period began with the First inauguration of Thomas Jefferson in 1801. The First inauguration of Andrew Jackson in 1829 marked the start of the next period in U.S. foreign policy.

The 1817 State of the Union Address was delivered by the fifth President of the United States, James Monroe, on December 2, 1817. This was Monroe's first annual message to the Fifteenth United States Congress and reflected on the nation's prosperity following the War of 1812.

The 1820 State of the Union Address was delivered by the 5th president of the United States James Monroe to the 16th United States Congress on November 14, 1820.

The 1821 State of the Union Address was delivered by the 5th president of the United States James Monroe to the 17th United States Congress on December 3, 1821.

The 1822 State of the Union Address was delivered by the 5th president of the United States James Monroe to the 17th United States Congress on December 3, 1822.

The 1851 State of the Union address was delivered by the 13th president of the United States Millard Fillmore to the United States Congress on December 2, 1851. This address, Fillmore's second annual message to Congress, focused on maintaining neutrality in foreign conflicts, enforcing laws regarding fugitive slaves, and preserving the Union.

References

- ↑ "Joint Meetings, Joint Sessions, & Inaugurations | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 "James Monroe - State of the Union Address -- 1819". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 19 October 2024.