The 1932 Christchurch tramway strike was an industrial dispute between tramway workers and their employers that took place in the city of Christchurch, New Zealand during the Great Depression. It lasted 16 days and led to the injury and arrest of many local people on both sides of the dispute.

During the Great Depression the Christchurch Tramway Board faced financial problems from falling revenue. In 1931 the Tramway Board attempted to cut salaries and working conditions, exploiting a legal loophole in the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act. The Tramway Workers' Union rejected the proposed changes and as a result the board dismissed the entire traffic staff and opened applications for replacement positions under the new conditions. To settle the dispute an independent mediator was brought in and largely found in the union's favour. Nonetheless, an atmosphere of mistrust between the board and workers manifested. [1]

In early 1932 the board proposed to rationing work hours for a period of two months to prevent redundancies, to which the union grudgingly agreed. When the period ended the board sought to extend the arrangement the union refused. The board responded by dismissing 12 employees (including the union president John Mathison) as a way to reduce costs. [2] The board's decision was seen as provocative and deliberate and the union retaliated by threatening industrial action if the 12 employees were not reinstated. The board refused and the union met on 1 May to vote on whether to take strike action. Mathison warned the meeting that if a strike was to occur the city "will be plunged into the first instalment of an industrial war", which was a grimly apt prediction. [1] Tensions were high nationwide at the time with major unemployment riots having broken out in Auckland, Wellington and Dunedin already. [3]

The union voted in favour of striking and the 700 members then marched, brandishing red banners, through the city to Cranmer Square as part of a planned celebration of International Workers' Day. Police forecasted unrest and warned local shopkeepers to secure their windows, though the day's events were peaceful in conduct. The tramway workers joined other activists and unemployed men (the newspaper The Press estimated the number exceeding 10,000) to hear speeches and resolutions. Such a display of industrial unity worried the board who cabled the government to request a suspension of the Act requiring certified motormen on trams. [1]

On Monday morning newspapers were published containing advertisements for new positions and notices to all employees that failure to report for work on Wednesday would result in their immediate dismissal. The same day the union offered to renegotiate the work rationing scheme if all employees were reinstated, but it was rejected by the board. [1] Due to the high number of unemployed men there was no shortage of applicants for the newly advertised positions. [4]

The first day of the strike was a peaceful one in which the board could only offer a greatly reduced daytime only service, resulting in many usual patrons walking to and from work that day. Several hundred strikers and their supporters had gathered at 6 am to watch trams go out of the yard and identified 39 employees who had refused to join the strike (scabs). A police escort was then given to subsequent services to prevent reprisals against the scab workers. On Thursday there were multiple police reports of mainly minor incidents of attempts at impeding the tram services, including shorting overhead wires with a length of steel and attempts to puncture tram tires using tacks. The homes of many scabs were also visited by groups of threatening unionists. [1]

The next day a tram was pelted with a volley of rocks heading up Fitzgerald Avenue. Many windows were smashed and the driver suffered minor injuries. Police confronted the assailants and melee combat broke out with police attacking with batons while some unionists and their supporters fashioned improvised clubs. Initially outnumbered the police were reinforced by dozens of previously sworn-in "special" constables, civilians sworn in under oath to act under police command, causing the unionists to flee. A total of 19 people were arrested, including 5 scabs. News of the open brawling shocked the city and prominent citizens worked to bring the two parties together while overall public sympathy for the strikers grew. A silent march of 300 strikers that night to Cathedral Square who were met at their arrival by a crowd of over 4000 supporters. The crowd was so large that people were blocking tramlines. When requested they cooperated in moving, only to shift on to tracks elsewhere. Tempers grew and fist fighting broke out between the attendees and police. The outnumbered police were forced into a corner by the Chief Post Office before drawing batons and driving the crowd back defusing a potential riot. Many were arrested and transported away using a fleet of commandeered taxis. [1]

A bus-load of police forestalled a potential attack on a tram in Hagley Park the next morning after which police discovered an assortment of clubs, discarded by the would-be attackers. At midday leaders of the two parties made their first attempt at a settlement. Each group was seated in separate rooms and unable to reach an agreement. The disagreement was due to the board's refusal to renege on its promise of permanent employment to the new workers it had hired since the start of the strike and the union would not end the strike until their members were reinstated in place of the replacements workers. The proposals were later passed by both parties to the head mediator Sir Arthur Donnelly, Q.C. who had the casting vote. [1]

Most of the strikers’ antagonism was against the "special" constables. [5] Most were members of the middle class and seen as partisan supporters of the board with no sympathy for the tram workers. Rugby players Beau Cottrell, George Hart and Jack Manchester were among the "specials" and drew particular hostility. That weekend a crowd of around 7000 (far exceeding normal attendance) went to Lancaster Park to watch Christchurch RFC (the club of Cottrell, Hart and Manchester) play Merivale-Papanui. The game was overshadowed by noisy chanting and jeering and after is completion half of the crowd formed outside the park for a demonstration. [1] Around 4000 people formed into a mass to block roads preventing the Christchurch RFC players leaving the ground. Several bottles were thrown and chants, referring disparagingly to the three players, were conveyed aggressively. Police reinforcements arrived and a column drew batons and engaged the crowd clearing a path and allowed the Black Maria carrying the players to leave. [1] [6]

Due to police being sent to Lancaster Park, many trams had insufficient police protection and several trams were attacked. On one such tram a conductor, William Henry Victor Laing, was punched in the face and went unattended during the chaos. Laing became infected with blood poisoning and died three weeks later on 29 May from the resulting complications. James Duncan Burke was charged with manslaughter but was found not guilty. [7]

The day after the rugby game the windows of two shops owned by "specials" had rocks thrown through them. The day after a rock was thrown through a tram window leading to the board covering tram windows with steel mesh and a high barbed wire fence around the barn to be built where the trams were stored at night. [1]

Following the confrontation at Lancaster Park the violence largely abated, though police and specials continued to patrol the suburbs, sandhills and Hagley Park. On 10 May the strike was called off. [1] The strike didn't end until 17 May after both sides agreed to accept the tribunal's decision. [8]

Donnelly, in his report to the tribunal, did not apportion blame for the events on anyone but did say he found the events without "necessity or excuse" and excessive given what he deemed a minor disagreement. He concluded that the board had acted unwisely by dismissing the employees and in particularly the president of the union (Mathison) and should have foreseen the potential for reprisals. He ruled that 60 of the new employees hired since the strike began be retained with the remaining staff being made up of striking workers with an hour rationing system. As a consequence 40 union members were dismissed instead of the initial 12. By the time of the ruling Mathison had accepted employment at the Christchurch Star-Sun instead, a move for which he was heavily criticised. [1]

Both the Tramway Workers' Union and local branches of the Labour Party proved to be outlets for frustrated workers and the unemployed. By voicing dissatisfaction here they became vital outlets for the most discontented in Christchurch and this was ironically a major factor in why the tramway strike failed to widen into a general uprising against the social disruption caused by the depression. [9]

At the 1933 local-body elections the Labour Party ticket (including Mathison) won a landslide victory for Tramway Board representatives. [10] It then made its first act the commitment to re-employ all the workers who were dismissed as a result of the strike. As vacancies arose the positions were offered to the dismissed employees and by 1935 all who wished so were once again employed by the Tramway Board, many giving many years loyal service to Christchurch's transportation service. [1]

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage, caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the Industrial Revolution, when mass labor became important in factories and mines. In most countries, strike actions were quickly made illegal, as factory owners had far more power than workers. Most Western countries partially legalized striking in the late 19th or early 20th centuries.

The Waihi miners' strike was a major strike action in 1912 by gold miners in the New Zealand town of Waihi. It is widely regarded as the most significant industrial action in the history of New Zealand's labour movement. It resulted in one striker being killed, one of only two deaths in industrial actions in New Zealand.

The Dublin lock-out was a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers which took place in Ireland's capital city of Dublin. The dispute lasted from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914, and is often viewed as the most severe and significant industrial dispute in Irish history. Central to the dispute was the workers' right to unionise.

The 1923 Victorian Police strike occurred in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. On the eve of the Melbourne Spring Racing Carnival in November 1923, half the police force in Melbourne went on strike over the operation of a supervisory system using labour spies. Riots and looting followed as crowds poured forth from Flinders Street railway station on the Friday and Saturday nights and made their way up Elizabeth and Swanston Streets, smashing shop windows, looting, and overturning trams.

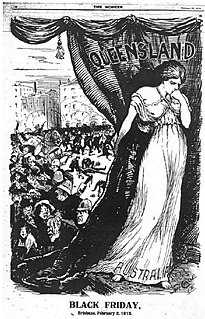

The 1912 Brisbane General Strike in Queensland, Australia, began when members of the Australian Tramway and Motor Omnibus Employees' Association were dismissed when they wore union badges to work on 18 January 1912. They then marched to Brisbane Trades Hall where a meeting was held, with a mass protest meeting of 10,000 people held that night in Market Square.

The 2006 Progressive Enterprises Dispute was an industrial dispute between New Zealand supermarket company Progressive Enterprises and employees represented by the National Distribution Union and the EPMU. On 25 August 2006, over 500 employees at Progressive's four distribution centres began a 48-hour strike supporting a demand for a national collective agreement involving an eight percent wage increase and pay parity between the four centres. On 26 August 2006 the company locked out the strikers indefinitely, suspending operations at its distribution centres, with suppliers delivering goods directly to the supermarkets and also setting up amateur small scale distribution centres in car parks of Countdown supermarkets. The dispute was resolved on 21 September 2006 when Progressive Enterprises agreed to pay parity and a 4.5% wage increase.

The Battle of Ballantyne Pier occurred in Ballantyne Pier during a docker's strike in Vancouver, British Columbia, in June 1935. The federally-owned dock was named for the head of the Harbours Board, which built it. There were ongoing strikes on the West Coast of North America in the Depression and it led to the right to collectively bargain and the rise of the I.L.W. U.

The Toledo Auto-Lite strike was a strike by a federal labor union of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) against the Electric Auto-Lite company of Toledo, Ohio, from April 12 to June 3, 1934.

The Christchurch tramway system was an extensive network in Christchurch, New Zealand, with steam and horse trams from 1882. Electric trams ran from 1905 to 1954, when the last line from Cashmere to Papanui was replaced by buses.

The 1877 Shamokin uprising occurred in Shamokin, Pennsylvania, in July 1877, as one of the several cities in the state where strikes occurred as part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The Great Strike was the first in the United States in which workers across the country united in an action against major companies. In many cities, the railroad workers were joined by other industrial workers in general strikes.

The General Strike of 1910 was a labor strike by trolley workers of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company that grew to a citywide riot and general strike in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Great Strike refers to a near general strike that took place in New Zealand from October 1913 to mid-January 1914. It was the largest and most disruptive strike in New Zealand's history. At its height, it brought the economy of New Zealand almost to a halt. Between 14,000 and 16,000 workers went on strike, out of a population of just over one million.

Mary Fitzgerald was an Irish-born South African political activist and is considered to have been the first female trade unionist in the country.

The Indianapolis streetcar strike of 1913 and the subsequent police mutiny and riots was a breakdown in public order in Indianapolis, Indiana. The events began as a workers strike by the union employees of the Indianapolis Traction & Terminal Company and their allies on Halloween night, October 31, 1913. The company was responsible for public transportation in Indianapolis, the capital city and transportation hub of the U.S. state of Indiana. The unionization effort was being organized by the Amalgamated Street Railway Employees of America who had successfully enforced strikes in other major United States cities. Company management suppressed the initial attempt by some of its employees to unionize and rejected an offer of mediation by the United States Department of Labor, which led to a rapid rise in tensions, and ultimately the strike. Government response to the strike was politically charged, as the strike began during the week leading up to public elections. The strike effectively shut down mass transit in the city and caused severe interruptions of statewide rail transportation and the 1913 city elections.

John "Jock" Mathison was a New Zealand politician of the Labour Party. He was famed for his skills as a chairman and well known for his "unmistakably Scottish" accent, eloquent speeches and dry sense of humour.

Industrial violence refers to acts of violence which occur within the context of industrial relations. These disputes can involve employers and employees, unions, employer organisations and the state. There is not a singular theory which can explain the conditions under which industrial conflicts become violent. However, there are a variety of partial explanations provided by theoretical frameworks on collective violence, social conflict and labor protest and militancy.

The anti-capitalist, anti-state and anti-domination political philosophy of anarchism has played a small, but important and colourful role in New Zealand politics.

The Battle of Lewes Road was a confrontation which took place in Brighton during the 1926 United Kingdom general strike.

The Vacaville tree pruners' strike of 1932 was a two-month strike beginning on November 14 by the CAWIU in Vacaville, California, United States. The strikers were protesting a cut in tree pruning wages from $1.40 for an eight-hour workday to $1.25 for a nine-hour workday. The strike was characterized by multiple incidences of violence, including a break-in at the Vacaville jail that resulted in the kidnapping and abuse of six arrested strike leaders. The strikers were ultimately unsuccessful in demanding higher wages and fewer hours and the CAWIU voted to end the strike on January 20, 1933.

The Saint John street railway strike of 1914 was a strike by workers on the street railway system in Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada, which lasted from 22–24 July 1914, with rioting by Saint John inhabitants occurring on 23 and 24 July. The strike was important for shattering the image of Saint John as a conservative town dominated primarily by ethnic and religious divisions, and highlighting tensions between railway industrialists and the local working population.