Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group and nation who are an indigenous people of Crimea. The formation and ethnogenesis of Crimean Tatars occurred during the 13th–17th centuries, uniting Cumans, who appeared in Crimea in the 10th century, with other peoples who had inhabited Crimea since ancient times and gradually underwent Tatarization, including Greeks, Italians, Armenians, Goths, Sarmatians, and others.

Alime Seitosmanovna Abdenanova — was a Crimean Tatar scout in the Red Army during World War II. After the German occupation of Crimea began in 1943 she led her reconnaissance group in the collection of intelligence about the positions of German and Romanian troops throughout the Kerch Peninsula, for which she was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. After the group was arrested by the Germans in February Abdenanova was tortured for over a month but refused to reveal any information to her captors. At the age of twenty she was executed in the outskirts of Simferopol on 5 April 1944. On 1 September 2014 by decree of Vladimir Putin she was posthumously declared a Hero of the Russian Federation, making her the sixteenth woman and first Crimean Tatar awarded the title.

Yadgar Sodiqovna Nasriddinova was an Uzbek Soviet engineer, politician, and high ranking member of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. After serving in a variety of posts in the Komsomol, she rose through the ranks of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and became a deputy in the Supreme Soviet from 1958 to 1974. Between 1959 and 1970, she was the Deputy Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and subsequently the chair of the Council of Nationalities of the Supreme Soviet until 1974. She was purged from the Communist Party in 1988 after the death of Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982) and during the corruption investigations in the Uzbek cotton scandal. She was rehabilitated and restored to party membership in 1991, when the allegations of bribery against her could not be substantiated. Nasriddinova was awarded the Order of Lenin four times over the course of her career, as well as twice receiving the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.

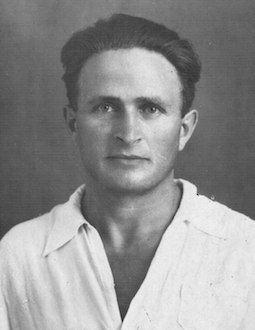

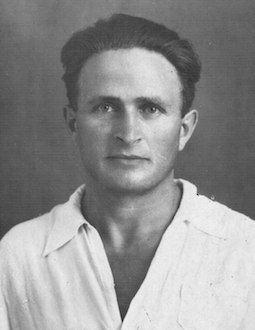

Abdraim Izmailovich Reshidov was the deputy commander of the 162nd Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment of the Soviet Air Forces during World War II, known as the Great Patriotic War in the USSR. In 1945 while he held the rank of Major he was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union for his first 166 missions in a Pe-2 during the war. After the war he was heavily involved in the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement, and swore to the government that he would publicly commit self-immolation if they continued to refuse him the right of return.

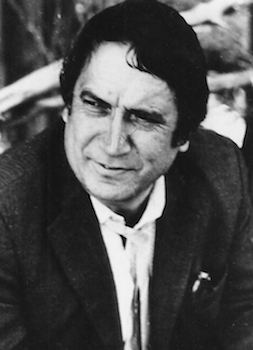

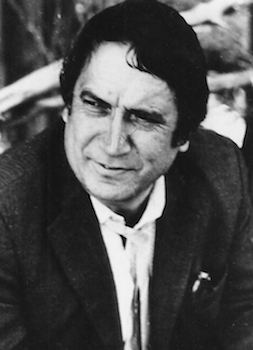

Yuri Bekirovich Osmanov was a scientist, engineer, Marxist–Leninist, and Crimean Tatar civil rights activist. He was one of the co-founders of the National Movement of Crimean Tatars, which sought full right of return of the Crimean Tatar people to their homeland and restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

Emir Üsein Çalbaş was a Crimean Tatar flying ace, squadron commander, test pilot, and friend of Amet-khan Sultan. He was nominated to receive the title Hero of the Soviet Union on two occasions but did not receive it.

Gulnara Tasimovna Bekirova is a Crimean Tatar historian, writer, and member of PEN International. In her work as a historian she was a consultant in the creation of the movie "Haytarma". As a writer, she has produced numerous papers and books about interethnic relations of deported Crimean Tatars and their fate under Soviet, Ukrainian, and Russian governance. She has criticized Russian textbooks for depicting Crimean Tatars as inferior and supporting in xenophobic stereotypes of Crimean Tatars from the Soviet era. As an active writer for RadioFreeEurope she has written articles on krymr about the present situation in Crimea as well as the role of Crimean Tatars in the Red Army and the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement.

The de-Tatarization of Crimea refers to the Soviet and Russian efforts to remove traces of the indigenous Crimean Tatar presence from the peninsula. De-Tatarization has manifested in various ways throughout history, from the full-scale deportation and exile of Crimean Tatars in 1944 to other measures such as the burning of Crimean Tatar books published in the 1920s and toponym renaming.

Abdulla Latif-zade was a Crimean Tatar literary critic, poet, writer, and translator who was executed during the purge of Crimean Tatar intellectuals in the Stalin era.

Seit Memetovich Tairov was the highest-ranking Crimean Tatar politician in Soviet Union after the Sürgün, having risen to prominence as a leader in Akkurgan and then first secretary of the Jizzakh regional committee of the Communist Party. A controversial figure among Crimean Tatars today, he is remembered for his staunch opposition to full right of return to Crimea. As a public supporter of "taking root" in Uzbekistan, he was one of the top signatories of the notorious "Letter of Seventeen" in March 1968 that downplayed Crimean Tatar struggles and discrimination in exile and urged Crimean Tatars to avoid "succumbing" to desires to return to Crimea.

Refat Fazylovich Appazov was a Soviet-Crimean Tatar rocket scientist and colleague of Sergei Korolev who served as head of the ballistics department of Energia from 1961 to 1988. Unlike most Crimean Tatars, he was spared special settler status and exile to Central Asia since the authorities forgot to include him in the deportation due to being in Izhevsk at the time. As a result, he was left cut off from the rest of Crimean Tatar society in the Soviet Union for much of his life. Nevertheless, he managed to become an engineer in OKB-1 and later a teacher at the prestigious Moscow Aviation Institute despite repeatedly facing discrimination. After keeping quiet about his Crimean Tatar identity for most of his life, he became heavily involved in the right of return movement after seeing the 1987 announcement about the conclusion by the Gromyko commission downplaying the entire issue and rejecting full right of return to Crimea. He went on to be a member of the second committee dedicated to considering the issue of Crimean Tatar return, which overturned the conclusions of the Gromyko commission, and in 1991 he was elected as a delegate of the Crimean Tatar Qurultay.

The "Letter of Seventeen" was a wildly unpopular open letter to the exiled Crimean Tatar community in published in Lenin Bayrağı in March 1968 condemning desire for right of return. Crimean Tatar civil rights activist Yuri Osmanov referred to it as the "letter of national traitors". The condescending letter opened with downplaying their major struggles and discrimination in Asia, urging their fellow Crimean Tatars to accept the situation and take root in Central Asia rather than supporting the right of return to Crimea that many Crimean Tatars dreamed of. In the middle, it claimed the September 1967 "rehabilitation" decree "radically solved their national question"; however, in reality, the widely despised decree, which initially confused some Crimean Tatars into thinking they were allowed to return to Crimea, only for them to be deported again, merely labeled Crimean Tatars as rehabilitated on paper without right to reparations or return and in addition to normalizing use of the despised terminology of "citizens of Tatar nationality who formerly lived in the Crimea" instead of the proper ethnonym of "Crimean Tatar". At the end, it painted return to Crimea as a romantic desire that one should suppress for the greater good and was subsequently co-signed by 17 relatively accomplished but not widely known members of the community who towed the party line and did not publicly desire right of return. After Crimean Tatars were allowed right of return to Crimea decades later, the letter was republished in Avdet on 15 March 1991 with commentary discouraging people from betraying their people in dire times like the signers of the letter did.

Rollan Kemalevich Kadyev was a Crimean Tatar physicist and civil rights activist in the Soviet Union. A defendant in the Tashkent process, he became known as a firebrand opponent of marginalization and delimination Crimean Tatars, publicly denouncing the restrictions on returning to Crimea as well as the government policy of claiming Crimean Tatars were not a distinct ethnic group that was exemplified by official use of the euphemism "people of Tatar nationality who formerly lived in the Crimea" instead of their proper ethnonym of "Crimean Tatar". For his activities such as distributing leaflets and verbally confronting those who endorsed the status quo against of national policy relating the Crimean Tatars, he was imprisoned on charges of "defaming the Soviet system", despite passionately making the case that discriminatory and assimilationist policies against Crimean Tatars was a huge deviation from proper Leninist national policy. Later on in his life he significantly softened his tone after a 1979 imprisonment for getting into a fight with a party organizer, controversially signing off an open letter critical of Ayshe Seitmuratova's activities with Radio Liberty, which was published in Lenin Bayrağı and Pravda Vostoka in February 1981.

Bekir Osmanov was a Crimean Tatar civil rights activist, agronomist, and partisan.

Decree No. 493 "On citizens of Tatar nationality, formerly living in the Crimea" was issued by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet on 5 September 1967 to placate and confuse the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement. Issued shortly after Crimean Tatar rights activists met with senior government officials to outline their grievances and demands for full rehabilitation, right of return, reparations, and restoration of the Crimean ASSR, the decree conceded to none of those demands but did normalize the government's euphemism "citizen of Tatar nationality formerly living in the Crimea" in lieu of the proper ethnonym of Crimean Tatar as per the policy of not acknowledging Crimean Tatars to be a distinct ethnic group as well as give the government a way of claiming that the issue was "solved". While other deported peoples such as the Chechens, Ingush, Kalmyks, Karachays, and Balkars had long since been permitted to return to their native lands and their republics were restored in addition to other forms of political rehabilitation as recognized peoples, the very same decree that rehabilitated those peoples in 1956 took on a genocidal tone towards internally deported Crimean Tatars, urging "national reunification" in the Tatar ASSR belonging to the distinct but similarly named Volga Tatars in lieu of restoration of the Crimean ASSR for Crimean Tatars who sought a national republic. While the 1956 decree and other internal government documents had long been using euphemisms in lieu of the term "Crimean Tatar", few Crimean Tatars were aware of the practice until seeing the decree proclaiming they were "rehabilitated" yet "firmly rooted" in current places of residence and bound to the then-current passport regime published in newspapers in September 1967. Nevertheless, several thousand Crimean Tatars attempted to return to Crimea upon seeing the decree and getting the mistaken impression that it meant they would be allowed to register in Crimea unhindered, much to their shock upon arrival that the propiska offices in Crimea continued to blatantly discriminate against Crimean Tatars, resulting in their redeportation.

Mustafa Veisovich Selimov was a Crimean Tatar communist leader, partisan, and civil rights activist. Having been the First Secretary of the Yalta Communist Party before the war, he served as the commissar of a partisan formation during the war before being exiled the Uzbek SSR as a Crimean Tatar, where he went on to hold leadership positions in the Ministry of Agriculture of the Uzbek SSR and become one of the original organizers of the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement, for which he received reprimand from party organs.

Dzhebbar Akimov was a Crimean Tatar teacher, writer who worked as editor of the newspaper "Qızıl Qırım" until the Sürgün. In exile, stood at the origins of the Crimean Tatar rights movement, becoming the leader of the Bekabad initiative group as well as authoring many documents about their plight for which he was expelled from the party in 1966, dubbed "the most active supporter of returning to Crimea" by the government in 1967, and eventually sentenced to three years in prison in 1972. Like many other leaders of the original Crimean Tatar rights movement, he considered himself a communist and opposed the prospect of members of movement associating with Soviet dissidents like Andrey Sakharov and Pyotr Grigorenko.

From 1 July to 5 August 1969, ten Crimean Tatar civil rights activists frequently dubbed the "Tashkent Ten" were tried in the Tashkent City Court under Articles 190-1 of the RSFSR Criminal Code and similar codes of other Soviet republics for activities the prosecutor Boris Berezovsky described as "being actively involved in solving the so-called Crimean Tatar issue [sic]". In line with standard practice at the time, the indictment and prosecution documents consistently labeled Crimean Tatars referred to in them not as Crimean Tatars but as "persons of Tatar nationality who previously lived in Crimea" and avoided acknowledging Crimean Tatars to be a distinct ethnic group, using degrading phrases like "so-called Crimean Tatars" to mock the defendants use of the ethnonym "Crimean Tatar", which the defendants in turn denounced during the proceedings.

"Gromyko commission", officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from among the Crimean Tatars. In reference to the head of the commission, Andrei Gromyko – was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from right of return to restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

The main wave of Crimean Tatar repatriation occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s when over 200,000 Crimean Tatars left Central Asia to return to Crimea whence they had been deported in 1944. While the Soviet government attempted to stifle mass return efforts for decades by denying them residence permits in Crimea or even recognition as a distinct ethnic group, activists continued to petition for the right of return. Eventually a series of commissions were created to publicly evaluate the prospects of allowing return, the first being the notorious Gromyko commission that lasted from 1987 to 1988 that issued declaring that "there was no basis" to allow exiled Crimean Tatars to return en masse to Crimea or restore the Crimean ASSR.