Related Research Articles

The Tatars, formerly also spelt Tartars, is an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar" across Eastern Europe and Asia. Initially, the ethnonym Tatar possibly referred to the Tatar confederation. That confederation was eventually incorporated into the Mongol Empire when Genghis Khan unified the various steppe tribes. Historically, the term Tatars was applied to anyone originating from the vast Northern and Central Asian landmass then known as Tartary, a term which was also conflated with the Mongol Empire itself. More recently, however, the term has come to refer more narrowly to related ethnic groups who refer to themselves as Tatars or who speak languages that are commonly referred to as Tatar.

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group and nation native to Crimea. The formation and ethnogenesis of Crimean Tatars occurred during the 13th–17th centuries, uniting Cumans, who appeared in Crimea in the 10th century, with other peoples who had inhabited Crimea since ancient times and gradually underwent Tatarization, including Ukrainian Greeks, Italians, Ottoman Turks, Goths, Sarmatians and many others. Despite the popular misconception, Crimean Tatars are not a diaspora of or subgroup of the Tatars.

The Crimean Khanate self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441–1783, the longest-lived of the Turkic khanates that succeeded the empire of the Golden Horde. Established by Hacı I Giray in 1441, it was regarded as the direct heir to the Golden Horde and to Desht-i-Kipchak.

Yadgar Sodiqovna Nasriddinova was an Uzbek Soviet engineer, politician, and high ranking member of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. After serving in a variety of posts in the Komsomol, she rose through the ranks of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and became a deputy in the Supreme Soviet from 1958 to 1974. Between 1959 and 1970, she was the Deputy Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and subsequently the chair of the Council of Nationalities of the Supreme Soviet until 1974. She was purged from the Communist Party in 1988 after the death of Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982) and during the corruption investigations in the Uzbek cotton scandal. She was rehabilitated and restored to party membership in 1991, when the allegations of bribery against her could not be substantiated. Nasriddinova was awarded the Order of Lenin four times over the course of her career, as well as twice receiving the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.

Yuri Bekirovich Osmanov was a scientist, engineer, Marxist–Leninist, and Crimean Tatar civil rights activist. He was one of the co-founders of the National Movement of Crimean Tatars, which sought full right of return of the Crimean Tatar people to their homeland and restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

Tatarophobia refers to the fear of, the hatred towards, the demonization of, or the prejudice against people who are generally referred to as Tatars, including but not limited to Volga, Siberian, and Crimean Tatars, although negative attitudes against the latter are by far the most severe, largely as a result of the Soviet media's long-standing practice of only depicting them in a negative way along with its practice of promoting negative stereotypes of them in order to provide a political justification for the deportation and marginalization of them.

Emir Üsein Çalbaş was a Crimean Tatar flying ace, squadron commander, test pilot, and friend of Amet-khan Sultan. He was nominated to receive the title Hero of the Soviet Union on two occasions but did not receive it.

The de-Tatarization of Crimea refers to the Soviet and Russian efforts to remove traces of the indigenous Crimean Tatar presence from the peninsula. De-Tatarization has been manifested in various ways throughout history, ranging from the full-scale deportation and exile of Crimean Tatars in 1944 to other measures such as the burning of Crimean Tatar books published in the 1920s and toponym renaming.

Ruslan Ismailovich Balbek is a Russian and former Ukrainian politician and former member of the State Duma from the United Russia party. A supporter of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, he has been highly critical of the Mejlis.

Abdulla Latif-zade was a Crimean Tatar literary critic, poet, writer, and translator who was executed during the purge of Crimean Tatar intellectuals in the Stalin era.

Seitumer Emin was a Crimean Tatar writer and poet. A partisan during World War II, he became an active member of the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement in exile.

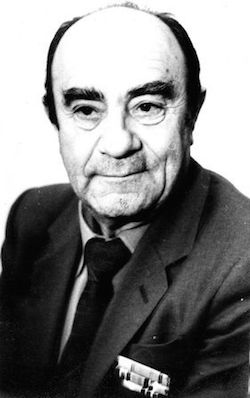

Seit Memetovich Tairov was the highest-ranking Crimean Tatar politician in Soviet Union after the Sürgün, having risen to prominence as a leader in Akkurgan and then first secretary of the Jizzakh regional committee of the Communist Party. A controversial figure among Crimean Tatars today, he is remembered for his staunch opposition to full right of return to Crimea. As a public supporter of "taking root" in Uzbekistan, he was one of the top signatories of the notorious "Letter of Seventeen" in March 1968 that downplayed Crimean Tatar struggles and discrimination in exile and urged Crimean Tatars to avoid "succumbing" to desires to return to Crimea.

The "Letter of Seventeen" was a wildly unpopular open letter to the exiled Crimean Tatar community in published in Lenin Bayrağı in March 1968 condemning desire for right of return among other Crimean Tatars. It was often dubbed "the letter of seventeen traitors."

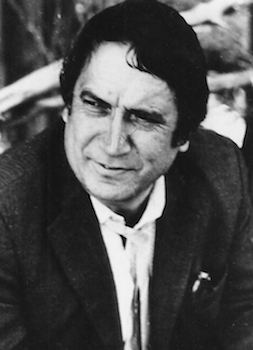

Rollan Kemalevich Kadyev was a Crimean Tatar physicist and civil rights activist in the Soviet Union. A defendant in the Tashkent process, he became known as a firebrand opponent of marginalization and delimination Crimean Tatars, publicly denouncing the restrictions on returning to Crimea as well as the government policy of claiming Crimean Tatars were not a distinct ethnic group that was exemplified by official use of the euphemism "people of Tatar nationality who formerly lived in the Crimea" instead of their proper ethnonym of "Crimean Tatar". For his activities such as distributing leaflets and verbally confronting those who endorsed the status quo against of national policy relating the Crimean Tatars, he was imprisoned on charges of "defaming the Soviet system", despite passionately making the case that discriminatory and assimilationist policies against Crimean Tatars was a huge deviation from proper Leninist national policy. Later on in his life he significantly softened his tone after a 1979 imprisonment for getting into a fight with a party organizer, controversially signing off an open letter critical of Ayshe Seitmuratova's activities with Radio Liberty, which was published in Lenin Bayrağı and Pravda Vostoka in February 1981.

Decree No. 493 "On citizens of Tatar nationality, formerly living in the Crimea" was issued by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet on 5 September 1967 proclaiming that "Citizens of Tatar nationality formerly living in the Crimea" [sic] were officially legally rehabilitated and had "taken root" in places of residence. For many years the government claimed that the decree "settled" the "Tatar problem", despite the fact that it did not restore the rights of Crimean Tatars and formally made clear that they were no longer recognized as a distinct ethnic group.

Dzhebbar Akimov was a Crimean Tatar teacher, writer who worked as editor of the newspaper "Qızıl Qırım" until the Sürgün. In exile, stood at the origins of the Crimean Tatar rights movement, becoming the leader of the Bekabad initiative group as well as authoring many documents about their plight for which he was expelled from the party in 1966, dubbed "the most active supporter of returning to Crimea" by the government in 1967, and eventually sentenced to three years in prison in 1972. Like many other leaders of the original Crimean Tatar rights movement, he considered himself a communist and opposed the prospect of members of movement associating with Soviet dissidents like Andrey Sakharov and Pyotr Grigorenko.

The Gromyko commission, officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from among the Crimean Tatars was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987 and led by Andrey Gromyko, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from right of return to restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

The 1968 Chirchik events happened on 21 April 1968 in Chirchik. Several Crimean Tatars gathered there to celebrate Derviza and Vladimir Lenin's birthday, but the authorities cracked down on the gathering.

Qaytarma is a form of Crimean Tatar folk dance and folk music characterised by cyclical motion. It is most commonly performed at weddings and on holidays.

Mustafa Seydulayevich Chachi was the director of the 5th division of the "Five-Year Plan of the Uzbek SSR" sovkhoz in Oqqoʻrgʻon District of Tashkent region, Uzbek SSR, and an innovator of organizing productive labor and implementing new methods. He was awarded the title of Hero of Socialist Labor in 1966 and was one of the signatories of the notorious letter of seventeen telling other Crimean Tatars to give up dreams of returning to Crimea.

References

- ↑ "THE TRIAL OF TEN CRIMEAN TATARS: TASHKENT, JULY-AUGUST 1969 (9.2)". A Chronicle of Current Events . 9 October 2013 [31 August 1969]. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ↑ Rusina, Yuliya (2022-05-15). Самиздат в СССР. Тексты и судьбы (in Russian). Litres. p. 61. ISBN 978-5-04-174850-0.

В мае 1969 г. в Ташкенте готовился большой процесс по делу группы крымских татар. Все они обвинялись по ст. 190-1 УК РСФСР

- 1 2 3 Bekirova, Gulnara (23 July 2015). "Ташкентский процесс". Крым.Реалии (in Russian). Retrieved 2021-10-11.

- ↑ Tashkent process 1976 , p. 206 "активное участие в деятельности по разрешению так называемого крымскотатарского вопроса"

- ↑ Tashkent process 1976 , p. 205 "Как установлено в ходе предварительного следствия в течение ряда лет, начиная с 1965 года, в Узбекистане действуют так называемые «инициативные группы» из лиц татарской национальности, ранее проживавших в Крыму."

- ↑ Tashkent process 1976, p. 314-321.

- ↑ Smirnov, Pyotr (1972). За пять лет--: документы и показания (in Russian). La Presse Libre. p. 146.

суд : — заседание Верховного суда УзССР: судья Сайфутдинов, народные заседатели Самойлова, Исфандиаров, прокурор Енкалов, защитники нахов, Заславский, Сафонов

- ↑ Eminov, Ruslan (2014-08-04). "Как судили крымских татар на высылке". Милли Фирка (in Russian). Retrieved 2023-12-06.