Related Research Articles

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group and nation native to Crimea. The formation and ethnogenesis of Crimean Tatars occurred during the 13th–17th centuries, uniting Cumans, who appeared in Crimea in the 10th century, with other peoples who had inhabited Crimea since ancient times and gradually underwent Tatarization, including Ukrainian Greeks, Italians, Ottoman Turks, Goths, Sarmatians and many others. Despite the popular misconception, Crimean Tatars are not a diaspora of or subgroup of the Tatars.

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441–1783, the longest-lived of the Turkic khanates that succeeded the empire of the Golden Horde. Established by Hacı I Giray in 1441, it was regarded as the direct heir to the Golden Horde and to Desht-i-Kipchak.

Below is the list of articles related to Crimean Tatars

Abdraim Izmailovich Reshidov was the deputy commander of the 162nd Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment of the Soviet Air Forces during World War II, known as the Great Patriotic War in the USSR. In 1945 while he held the rank of major he was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union for his first 166 missions in a Pe-2 during the war. After the war he was heavily involved in the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement, and swore to the government that he would publicly commit self-immolation if they did not let him live in Crimea.

Yuri Bekirovich Osmanov was a scientist, engineer, Marxist–Leninist, and Crimean Tatar civil rights activist. He was one of the co-founders of the National Movement of Crimean Tatars, which sought full right of return of the Crimean Tatar people to their homeland and restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

Emir Üsein Çalbaş was a Crimean Tatar flying ace, squadron commander, test pilot, and friend of Amet-khan Sultan. He was nominated to receive the title Hero of the Soviet Union on two occasions but did not receive it.

Ayşe Seitmuratova is a Crimean Tatar civil rights activist.

The de-Tatarization of Crimea refers to the Soviet and Russian efforts to remove traces of the indigenous Crimean Tatar presence from the peninsula. De-Tatarization has been manifested in various ways throughout history, ranging from the full-scale deportation and exile of Crimean Tatars in 1944 to other measures such as the burning of Crimean Tatar books published in the 1920s and toponym renaming.

Seit Memetovich Tairov was the highest-ranking Crimean Tatar politician in Soviet Union after the Sürgün, having risen to prominence as a leader in Akkurgan and then first secretary of the Jizzakh regional committee of the Communist Party. A controversial figure among Crimean Tatars today, he is remembered for his staunch opposition to full right of return to Crimea. As a public supporter of "taking root" in Uzbekistan, he was one of the top signatories of the notorious "Letter of Seventeen" in March 1968 that downplayed Crimean Tatar struggles and discrimination in exile and urged Crimean Tatars to avoid "succumbing" to desires to return to Crimea.

Refat Fazylovich Appazov was a Soviet-Crimean Tatar rocket scientist and colleague of Sergei Korolev who served as head of the ballistics department of Energia from 1961 to 1988. Unlike most Crimean Tatars, he was spared special settler status and exile to Central Asia since the authorities forgot to include him in the deportation due to being in Izhevsk at the time. As a result, he was left cut off from the rest of Crimean Tatar society in the Soviet Union for much of his life. Nevertheless, he managed to become an engineer in OKB-1 and later a teacher at the prestigious Moscow Aviation Institute despite repeatedly facing discrimination. After keeping quiet about his Crimean Tatar identity for most of his life, he became heavily involved in the right of return movement after seeing the 1987 announcement about the conclusion by the Gromyko commission downplaying the entire issue and rejecting full right of return to Crimea. He went on to be a member of the second committee dedicated to considering the issue of Crimean Tatar return, which overturned the conclusions of the Gromyko commission, and in 1991 he was elected as a delegate of the Crimean Tatar Qurultay.

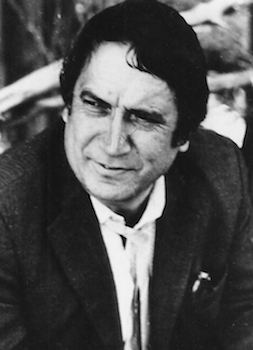

Rollan Kemalevich Kadyev was a Crimean Tatar physicist and civil rights activist in the Soviet Union. A defendant in the Tashkent process, he became known as a firebrand opponent of marginalization and delimination Crimean Tatars, publicly denouncing the restrictions on returning to Crimea as well as the government policy of claiming Crimean Tatars were not a distinct ethnic group that was exemplified by official use of the euphemism "people of Tatar nationality who formerly lived in the Crimea" instead of their proper ethnonym of "Crimean Tatar". For his activities such as distributing leaflets and verbally confronting those who endorsed the status quo against of national policy relating the Crimean Tatars, he was imprisoned on charges of "defaming the Soviet system", despite passionately making the case that discriminatory and assimilationist policies against Crimean Tatars was a huge deviation from proper Leninist national policy. Later on in his life he significantly softened his tone after a 1979 imprisonment for getting into a fight with a party organizer, controversially signing off an open letter critical of Ayshe Seitmuratova's activities with Radio Liberty, which was published in Lenin Bayrağı and Pravda Vostoka in February 1981.

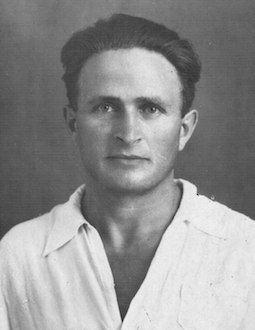

Bekir Osmanov was a Crimean Tatar civil rights activist, agronomist, and partisan.

Decree No. 493 "On citizens of Tatar nationality, formerly living in the Crimea" was issued by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet on 5 September 1967 proclaiming that "Citizens of Tatar nationality formerly living in the Crimea" [sic] were officially legally rehabilitated and had "taken root" in places of residence. For many years the government claimed that the decree "settled" the "Tatar problem", despite the fact that it did not restore the rights of Crimean Tatars and formally made clear that they were no longer recognized as a distinct ethnic group.

Mustafa Veisovich Selimov was a Crimean Tatar communist leader, partisan, and civil rights activist. Having been the First Secretary of the Yalta Communist Party before the war, he served as the commissar of a partisan formation during the war before being exiled the Uzbek SSR as a Crimean Tatar, where he went on to hold leadership positions in the Ministry of Agriculture of the Uzbek SSR and become one of the original organizers of the Crimean Tatar civil rights movement, for which he received reprimand from party organs.

The National Division of Crimean Tatars is a Crimean Tatar civil rights organization that was highly active in the late Soviet era.

The OKND was an anti-communist grouping of Crimean Tatars and the successor of the Central Initiative Group in the late Soviet era. It was formed in opposition to the Leninist NDKT.

The Gromyko Commission, officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from Among the Crimean Tatars was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987 and led by Andrey Gromyko, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from right of return to restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

The Crimean Tatar civil rights movement was a loosely-organized movement among the exiled Crimean Tatar nation that manifested throughout the second half of the 20th century, with the primary goals of regaining recognition as a distinct ethnic group, the right to live in Crimea, and restoration of the Crimean ASSR. Although the origins of the movement date back to the 1950s when its leaders were originally exclusively composed of party workers and Red Army veterans, who were confident that the union would soon fully rehabilitate them in accordance with proper adherence to Leninist national policy, as decades passed and the party remained hostile to even the most basic requests from Crimean Tatar petitions and deletions, a split eventually emerged in the movement; many youths who were deported as children gave up hope in communism and took issue with the Leninist line towed by leaders of the movement. Eventually in 1989 the Soviet government lifted the restrictions on moving to Crimea from all exiled Crimean Tatars, and began the rehabilitation process. Since then, in the period of a few years, over 200,000 Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea, but they continue to lack the status of titular people in any part of Crimea.

Mustafa Seydulayevich Chachi was the director of the 5th division of the "Five-Year Plan of the Uzbek SSR" sovkhoz in Oqqoʻrgʻon District of Tashkent region, Uzbek SSR, and an innovator of organizing productive labor and implementing new methods. He was awarded the title of Hero of Socialist Labor in 1966 and was one of the signatories of the notorious letter of seventeen telling other Crimean Tatars to give up dreams of returning to Crimea.

Memet Bilyalovich Molochnikov was a Crimean Tatar commissar, Communist Party member, partisan, and military lawyer.

References

- ↑ Guboglo 1992, p. 188-189.

- ↑ Guboglo 1992, p. 172.

- ↑ Bekirova 2005, p. 203.

- ↑ Smoly 2004, p. 180-182.

- ↑ Guboglo 1998, p. 654.

- ↑ Национального движения крымских татар. "Об участниках программы "Мубарекская и Крымская зоны"". НДКТ (in Russian). Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- 1 2 Guboglo 1992, p. 189.

Bibliography

- Bekirova, Gulnara (2005). Крым и крымские татары в XIX-XX веках: сборник статей (in Russian). ISBN 978-5-85167-057-2.

- Guboglo, Mikhail (1992). Крымскотатарское национальное движение: Документы, материалы, хроника (in Russian). Russian academy of Sciences. pp. 188–189.

- Guboglo, Mikhail (1998). Языки этнической мобилизации (in Russian). Языки русской культуры. ISBN 978-5-457-45045-5.

- Smoly, Valery (2004). Кримські татари: шлях до повернення : кримськотатарський національний рух, друга половина 1940-х-початок 1990-х років очима радянських спецслужб : збірник документів та матеріалів (in Russian). Ін-т історії України. ISBN 978-966-02-3285-3.