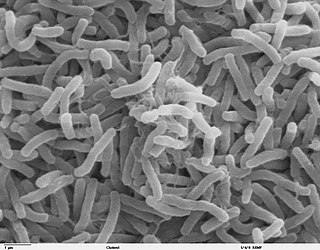

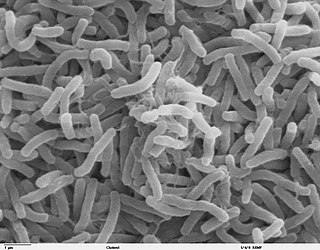

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea lasting a few days. Vomiting and muscle cramps may also occur. Diarrhea can be so severe that it leads within hours to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. This may result in sunken eyes, cold skin, decreased skin elasticity, and wrinkling of the hands and feet. Dehydration can cause the skin to turn bluish. Symptoms start two hours to five days after exposure.

Vibrio cholerae is a species of Gram-negative, facultative anaerobe and comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in brackish or saltwater where they attach themselves easily to the chitin-containing shells of crabs, shrimp, and other shellfish. Some strains of V. cholerae are pathogenic to humans and cause a deadly disease called cholera, which can be derived from the consumption of undercooked or raw marine life species or drinking contaminated water.

El Tor is a particular strain of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera. Also known as V. cholerae biotype eltor, it has been the dominant strain in the seventh global cholera pandemic. It is distinguished from the classic strain at a genetic level, although both are in the serogroup O1 and both contain Inaba, Ogawa and Hikojima serotypes. It is also distinguished from classic biotypes by the production of hemolysins.

Vibrio is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, possessing a curved-rod (comma) shape, several species of which can cause foodborne infection, usually associated with eating undercooked seafood. Being highly salt tolerant and unable to survive in fresh water, Vibrio spp. are commonly found in various salt water environments. Vibrio spp. are facultative anaerobes that test positive for oxidase and do not form spores. All members of the genus are motile. They are able to have polar or lateral flagellum with or without sheaths. Vibrio species typically possess two chromosomes, which is unusual for bacteria. Each chromosome has a distinct and independent origin of replication, and are conserved together over time in the genus. Recent phylogenies have been constructed based on a suite of genes.

The fifth cholera pandemic (1881–1896) was the fifth major international outbreak of cholera in the 19th century. The endemic origin of the pandemic, as had its predecessors, was in the Ganges Delta in West Bengal. While the Vibrio cholerae bacteria had not been able to spread to western Europe until the 19th century, faster and improved modes of modern transportation, such as steamships and railways, reduced the duration of the journey considerably and facilitated the transmission of cholera and other infectious diseases. During the fourth 1863–1875 cholera pandemic, the third International Sanitary Conference convened in 1866 in Constantinople had identified religious pilgrimages to be "the most powerful of all causes" of cholera and again Hindu and Muslim pilgrimages were an important factor in the spread of the disease.

The seventh cholera pandemic is the seventh major outbreak of cholera beginning in 1961 and continuing to the present. Cholera has become endemic in many countries. In 2017, WHO announced a global strategy aiming to end the pandemic by 2030.

The 2009 flu pandemic in Asia, part of an epidemic in 2009 of a new strain of influenza A virus subtype H1N1 causing what has been commonly called swine flu, afflicted at least 394,133 people in Asia with 2,137 confirmed deaths: there were 1,035 deaths confirmed in India, 737 deaths in China, 415 deaths in Turkey, 192 deaths in Thailand, and 170 deaths in South Korea. Among the Asian countries, South Korea had the most confirmed cases, followed by China, Hong Kong, and Thailand.

The 2010s Haiti cholera outbreak was the first modern large-scale outbreak of cholera—a disease once considered beaten back largely due to the invention of modern sanitation. The disease was reintroduced to Haiti in October 2010, not long after the disastrous earthquake earlier that year, and since then cholera has spread across the country and become endemic, causing high levels of both morbidity and mortality. Nearly 800,000 Haitians have been infected by cholera, and more than 9,000 have died, according to the United Nations (UN). Cholera transmission in Haiti today is largely a function of eradication efforts including WASH, education, oral vaccination, and climate variability. Early efforts were made to cover up the source of the epidemic, but thanks largely to the investigations of journalist Jonathan M. Katz and epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux, it is widely believed to be the result of contamination by infected United Nations peacekeepers deployed from Nepal. In terms of total infections, the outbreak has since been surpassed by the war-fueled 2016–2021 Yemen cholera outbreak, although the Haiti outbreak is still one of the most deadly modern outbreaks. After a three-year hiatus, new cholera cases reappeared in October 2022.

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organization factsheet in March 2022. Additionally, there have been many documented major local cholera outbreaks, such as a 1991–1994 outbreak in South America and, more recently, the 2016–2021 Yemen cholera outbreak.

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century included long-standing epidemic threats such as smallpox, typhus, yellow fever, and scarlet fever. In addition, cholera emerged as an epidemic threat and spread worldwide in six pandemics in the nineteenth century.

An outbreak of cholera began in Yemen in October 2016. The outbreak peaked in 2017 with over 2,000 reported deaths in that year alone. In 2017 and 2019, war-torn Yemen accounted for 84% and 93% of all cholera cases in the world, with children constituting the majority of reported cases. As of November 2021, there have been more than 2.5 million cases reported, and more than 4,000 people have died in the Yemen cholera outbreak, which the United Nations deemed the worst humanitarian crisis in the world at that time. However, the outbreak has substantially decreased by 2021, with a successful vaccination program implemented and only 5,676 suspected cases with two deaths reported between January 1 and March 6 of 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic began in Asia in Wuhan, Hubei, China, and has spread widely through the continent. As of 30 May 2024, at least one case of COVID-19 had been reported in every country in Asia except Turkmenistan.

In Lebanon, the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has resulted in 1,238,552 confirmed cases and 10,936 all-time deaths after COVID-19 was confirmed to have reached Lebanon in February 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt was a part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The virus was confirmed to have reached Egypt on 14 February 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have reached Oceania on 25 January 2020 with the first confirmed case reported in Melbourne, Australia. The virus has spread to all sovereign states and territories in the region. Australia and New Zealand were praised for their handling of the pandemic in comparison to other Western nations, with New Zealand and each state in Australia wiping out all community transmission of the virus several times even after re-introduction in the community.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Eswatini was a part of the ongoing worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have reached Eswatini in March 2020.

In May 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) made an emergency announcement of the existence of a multi-country outbreak of mpox, a viral disease then commonly known as "monkeypox". The initial cluster of cases was found in the United Kingdom, where the first case was detected in London on 6 May 2022 in a patient with a recent travel history from Nigeria where the disease has been endemic. On 16 May, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) confirmed four new cases with no link to travel to a country where mpox is endemic. Subsequently, cases have been reported from many countries and regions. The outbreak marked the first time mpox had spread widely outside Central and West Africa. The disease had been circulating and evolving in human hosts over a number of years prior to the outbreak and was caused by the clade IIb variant of the virus.

The 2022 mpox outbreak in Asia is a part of the ongoing outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak was reported in Asia on 20 May 2022 when Israel reported a suspected case of mpox, which was confirmed on 21 May. As of 10 August 2022, seven West Asian, three Southeast Asian, three East Asian and one South Asian country, along with Russia, have reported confirmed cases.

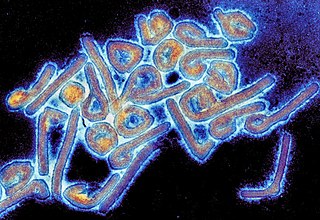

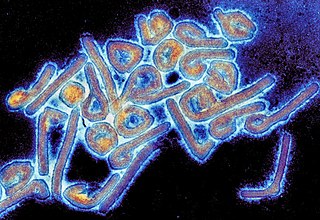

The 2022–2023 Uganda Ebola outbreak was an outbreak of the Sudan ebolavirus, which causes Ebola, from 20 September 2022 until 10 January 2023 in the Western and Central Regions of Uganda. Over 160 people were infected, including 77 people who died. It was Uganda's fifth outbreak with Sudan ebolavirus. The Ugandan Ministry of Health declared the outbreak on 20 September 2022. As of 25 October 2022, there were confirmed cases in the Mubende, Kyegegwa, Kassanda, Kagadi, Bunyanga, Kampala and Wakiso districts. As of 24 October 2022, there were a total of 90 confirmed or probable cases and 44 deaths. On 12 October, the first recorded death in the capital of Kampala occurred; 12 days later on 24 October, there had been a total of 14 infections in the capital in the last two days. On 11 January 2023 after 42 days without new cases the outbreak was declared over.

A disease outbreak was first reported in Equatorial Guinea on 7 February 2023 and, on 13 February 2023, it was identified as being Marburg virus disease. It was the first time the disease was detected in the country. As of 4 April 2023, there were 14 confirmed cases and 28 suspected cases, including ten confirmed deaths from the disease in Equatorial Guinea. On 8 June 2023, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak over. In total, 17 laboratory-confirmed cases and 12 deaths were recorded. All the 23 probable cases reportedly died. Four patients recovered from the virus and have been enrolled in a survivors programme to receive psychosocial and other post-recovery support.