Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity of the condition is variable.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1, the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus. The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the syndrome caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak. In the 2010s, Chinese scientists traced the virus through the intermediary of Asian palm civets to cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township, Yunnan.

Atypical pneumonia, also known as walking pneumonia, is any type of pneumonia not caused by one of the pathogens most commonly associated with the disease. Its clinical presentation contrasts to that of "typical" pneumonia. A variety of microorganisms can cause it. When it develops independently from another disease, it is called primary atypical pneumonia (PAP).

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a very small cell wall-less bacterium in the class Mollicutes. It is a human pathogen that causes the disease mycoplasma pneumonia, a form of atypical bacterial pneumonia related to cold agglutinin disease. M. pneumoniae is characterized by the absence of a peptidoglycan cell wall and resulting resistance to many antibacterial agents. The persistence of M. pneumoniae infections even after treatment is associated with its ability to mimic host cell surface composition.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), also called human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) and human orthopneumovirus, is a contagious virus that causes infections of the respiratory tract. It is a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus. Its name is derived from the large cells known as syncytia that form when infected cells fuse.

Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is a term often used as a synonym for pneumonia but can also be applied to other types of infection including lung abscess and acute bronchitis. Symptoms include shortness of breath, weakness, fever, coughing and fatigue. A routine chest X-ray is not always necessary for people who have symptoms of a lower respiratory tract infection.

Mycoplasma pneumonia is a form of bacterial pneumonia caused by the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Swine influenza is an infection caused by any of several types of swine influenza viruses. Swine influenza virus (SIV) or swine-origin influenza virus (S-OIV) refers to any strain of the influenza family of viruses that is endemic in pigs. As of 2009, identified SIV strains include influenza C and the subtypes of influenza A known as H1N1, H1N2, H2N1, H3N1, H3N2, and H2N3.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia contracted by a person outside of the healthcare system. In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is seen in patients who have recently visited a hospital or who live in long-term care facilities. CAP is common, affecting people of all ages, and its symptoms occur as a result of oxygen-absorbing areas of the lung (alveoli) filling with fluid. This inhibits lung function, causing dyspnea, fever, chest pains and cough.

Canine influenza is influenza occurring in canine animals. Canine influenza is caused by varieties of influenzavirus A, such as equine influenza virus H3N8, which was discovered to cause disease in canines in 2004. Because of the lack of previous exposure to this virus, dogs have no natural immunity to it. Therefore, the disease is rapidly transmitted between individual dogs. Canine influenza may be endemic in some regional dog populations of the United States. It is a disease with a high morbidity but a low incidence of death.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or nosocomial pneumonia refers to any pneumonia contracted by a patient in a hospital at least 48–72 hours after being admitted. It is thus distinguished from community-acquired pneumonia. It is usually caused by a bacterial infection, rather than a virus.

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu" or just "flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms begin one to four days after exposure to the virus and last for about two to eight days. Diarrhea and vomiting can occur, particularly in children. Influenza may progress to pneumonia from the virus or a subsequent bacterial infection. Other complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, meningitis, encephalitis, and worsening of pre-existing health problems such as asthma and cardiovascular disease.

Influenza-like illness (ILI), also known as flu-like syndrome or flu-like symptoms, is a medical diagnosis of possible influenza or other illness causing a set of common symptoms. These include fever, shivering, chills, malaise, dry cough, loss of appetite, body aches, nausea, and sneezing typically in connection with a sudden onset of illness. In most cases, the symptoms are caused by cytokines released by immune system activation, and are thus relatively non-specific.

The 2009 swine flu pandemic, caused by the H1N1/swine flu/influenza virus and declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) from June 2009 to August 2010, was the third recent flu pandemic involving the H1N1 virus. The first identified human case was in La Gloria, Mexico, a rural town in Veracruz. The virus appeared to be a new strain of H1N1 that resulted from a previous triple reassortment of bird, swine, and human flu viruses which further combined with a Eurasian pig flu virus, leading to the term "swine flu".

Robert Merritt Chanock was an American pediatrician and virologist who made major contributions to the prevention and treatment of childhood respiratory infections in more than 50 years spent at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Pneumonia can be classified in several ways, most commonly by where it was acquired, but may also by the area of lung affected or by the causative organism. There is also a combined clinical classification, which combines factors such as age, risk factors for certain microorganisms, the presence of underlying lung disease or systemic disease and whether the person has recently been hospitalized.

Chronic Mycoplasma pneumonia and Chlamydia pneumonia infections are associated with the onset and exacerbation of asthma. These microbial infections result in chronic lower airway inflammation, impaired mucociliary clearance, an increase in mucous production and eventually asthma. Furthermore, children who experience severe viral respiratory infections early in life have a high possibility of having asthma later in their childhood. These viral respiratory infections are mostly caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and human rhinovirus (HRV). Although RSV infections increase the risk of asthma in early childhood, the association between asthma and RSV decreases with increasing age. HRV on the other hand is an important cause of bronchiolitis and is strongly associated with asthma development. In children and adults with established asthma, viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), especially HRVs infections, can produce acute exacerbations of asthma. Thus, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and human rhinoviruses are microbes that play a major role in non-atopic asthma.

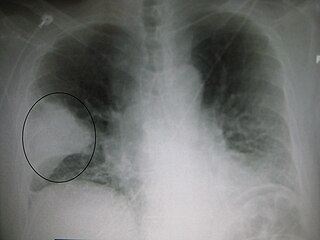

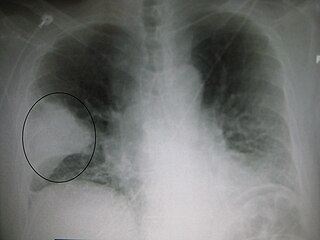

Necrotizing pneumonia (NP), also known as cavitary pneumonia or cavitatory necrosis, is a rare but severe complication of lung parenchymal infection. In necrotizing pneumonia, there is a substantial liquefaction following death of the lung tissue, which may lead to gangrene formation in the lung. In most cases patients with NP have fever, cough and bad breath, and those with more indolent infections have weight loss. Often patients clinically present with acute respiratory failure. The most common pathogens responsible for NP are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diagnosis is usually done by chest imaging, e.g. chest X-ray, CT scan. Among these CT scan is the most sensitive test which shows loss of lung architecture and multiple small thin walled cavities. Often cultures from bronchoalveolar lavage and blood may be done for identification of the causative organism(s). It is primarily managed by supportive care along with appropriate antibiotics. However, if patient develops severe complications like sepsis or fails to medical therapy, surgical resection is a reasonable option for saving life.

In the waning months of 2022, the first northern hemisphere autumn with the nearly full relaxation of public health precautions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals in the United States and Canada began to see overwhelming numbers of pediatric care patients, primarily driven by a massive upswing in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) cases, but also flu, rhinovirus, enterovirus, and SARS-CoV-2.

In late 2023, an outbreak of mycoplasma pneumonia occurred in Ohio in the United States, primarily affecting children. Despite it occurring at around the same time, experts say that it is unrelated to the 2023 Chinese pneumonia outbreak. The average age of children affected is eight years old, with some cases being as young as three. As of December 1, 2023, investigation as to the cause is still ongoing.