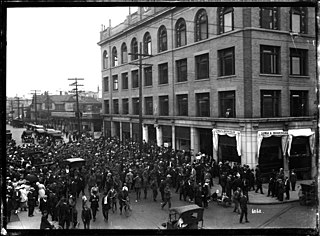

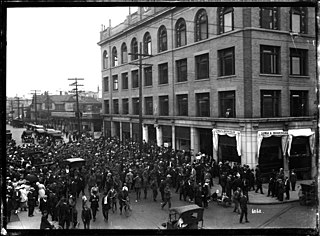

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike and industrial action in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the Industrial Revolution, when mass labor became important in factories and mines. As striking became a more common practice, governments were often pushed to act. When government intervention occurred, it was rarely neutral or amicable. Early strikes were often deemed unlawful conspiracies or anti-competitive cartel action and many were subject to massive legal repression by state police, federal military power, and federal courts. Many Western nations legalized striking under certain conditions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The interests of the employees are commonly presented by representatives of a trade union to which the employees belong. A collective agreement reached by these negotiations functions as a labour contract between an employer and one or more unions, and typically establishes terms regarding wage scales, working hours, training, health and safety, overtime, grievance mechanisms, and rights to participate in workplace or company affairs. Such agreements can also include 'productivity bargaining' in which workers agree to changes to working practices in return for higher pay or greater job security.

Founded in 1925, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids, commonly referred to as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), was the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The BSCP gathered a membership of 18,000 passenger railway workers across Canada, Mexico, and the United States.

Justice for Janitors (JfJ) is a social movement organization that fights for the rights of janitors across the US and Canada. It was started on June 15, 1990, in response to the low wages and minimal health-care coverage that janitors received. Justice for Janitors includes more than 225,000 janitors in at least 29 cities in the United States and at least four cities in Canada. Members fight for better wages, better conditions, improved healthcare, and full-time opportunities.

The Graduate Student Organizing Committee (GSOC) is a labor union representing graduate teaching and research assistants at New York University (NYU).

The Temple University Graduate Students Association (TUGSA) is a graduate employee union that is located at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the United States.

Community unionism, also known as reciprocal unionism, refers to the formation of alliances between unions and non-labour groups in order to achieve common goals. These unions seek to organize the employed, unemployed, and underemployed. They press for change in the workplace and beyond, organizing around issues such as welfare reform, health care, jobs, housing, and immigration. Individual issues at work are seen as being a part of broader societal problems which they seek to address. Unlike trade unions, community union membership is not based on the workplace- it is based on common identities and issues. Alliances forged between unions and other groups may have a primary identity based on affiliations of religion, ethnic group, gender, disability, environmentalism, neighborhood residence, or sexuality.

Graduate student employee unionization, or academic student employee unionization, refers to labor unions that represent students who are employed by their college or university to teach classes, conduct research and perform clerical duties. As of 2014, there were at least 33 US graduate employee unions, 18 unrecognized unions in the United States, and 23 graduate employee unions in Canada. By 2019, it is estimated that there were 83,050 unionized student employees in certified bargaining units in the United States. As of 2023, there were at least 156 US graduate student employee unions and 23 graduate student employee unions in Canada.

Labor relations or labor studies is a field of study that can have different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. In an international context, it is a subfield of labor history that studies the human relations with regard to work in its broadest sense and how this connects to questions of social inequality. It explicitly encompasses unregulated, historical, and non-Western forms of labor. Here, labor relations define "for or with whom one works and under what rules. These rules determine the type of work, type and amount of remuneration, working hours, degrees of physical and psychological strain, as well as the degree of freedom and autonomy associated with the work." More specifically in a North American and strictly modern context, labor relations is the study and practice of managing unionized employment situations. In academia, labor relations is frequently a sub-area within industrial relations, though scholars from many disciplines including economics, sociology, history, law, and political science also study labor unions and labor movements. In practice, labor relations is frequently a subarea within human resource management. Courses in labor relations typically cover labor history, labor law, union organizing, bargaining, contract administration, and important contemporary topics.

The Memphis sanitation strike began on February 12, 1968, in response to the deaths of sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker. The deaths served as a breaking point for more than 1,300 African American men from the Memphis Department of Public Works as they demanded higher wages, time and a half overtime, dues check-off, safety measures, and pay for the rainy days when they were told to go home.

A wildcat strike is a strike action undertaken by unionised workers without union leadership's authorization, support, or approval; this is sometimes termed an unofficial industrial action. The legality of wildcat strikes varies between countries and over time.

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) is the largest trade union of public employees in the United States. It represents 1.3 million public sector employees and retirees, including health care workers, corrections officers, sanitation workers, police officers, firefighters, and childcare providers. Founded in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1932, AFSCME is part of the AFL–CIO, one of the two main labor federations in the United States. AFSCME has had four presidents since its founding.

The Graduate Employees' Organization at UIUC (GEO) is a labor union created to defend and extend the bargaining and employment rights of Graduate Employees at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

Theresa El-Amin is an African-American civil rights activist, union organizer and former member of the Green Party of the United States Steering Committee.

Oliver Harvey was an African American janitor at Duke University and founding president of the Local 77 chapter of American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO. He spearheaded the movement to unionize Duke University employees during the 1960s.

The Teaching Assistants Association (TAA) is a graduate student employee union formed at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1966. It is credited as the first graduate student labor union. Following voluntary recognition by the university as the teaching assistants' bargaining agent in 1969, negotiations resulted in a 1970 strike, which secured "bread-and-butter" gains such as job security alongside grievance procedures. Their major unmet demand from their strike—the inclusion of teaching assistants and students in the course planning process—went unfulfilled. The TAA struck again in 1980 and lost its union recognition until 1986. The union's protest at the Wisconsin State Capitol building began the 2011 Wisconsin protests.

Immediately following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the Silent Vigil was a social protest at Duke University that not only demanded collective bargaining rights for AFSCME Local 77, the labor union for nonacademic employees, but also advocated against racial discrimination on campus and in the surrounding community of Durham, North Carolina. Occurring from April 4, 1968, to April 12, 1968, members of the University Christian Movement began planning a campus-wide vigil in memoriam of Dr. King. Another group of undergraduate students called for a protest march to address prevalent issues concerning the primarily African-American nonacademic employees at Duke in Local 77. Together, both student groups, along with the support of Local 77, most of the teaching faculty, and civilians not affiliated with the university, sparked a non-violent demonstration that involved over 2,000 participants, making it the largest in Duke's history. The Silent Vigil stands out from other contemporary college movements due to the collaboration between primarily white students and faculty, and mainly African-American workers. Furthermore, unlike rowdier protests at the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University, Duke's Silent Vigil received considerable praise for its peaceful approach, especially considering its surrounding Southern backdrop. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, the Silent Vigil not only aimed to externally change Duke's white, privileged, and apathetic image in the eyes of the Durham community, but also internally set a powerful precedent on Duke's campus for student activism in the future.

The Duke University Hospital unionization drives of the 1970s involved two distinct organizing efforts aimed at uniting the service workers of Duke Hospital. The drives were defined by their fusion of the fight for worker’s rights with the battle for racial equality. The first drive in 1974 was characterized by unity amongst the workers involved, including members of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees Local 77, and a strong spirit of activism, but failed due to political infighting and resistance by the University. The second drive, organized by a representative of the national American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) in 1978, was formed on the ideals of inclusion and keeping the union free of politics. The 1978 drive failed as well, in part due to the management company that Duke hired to instill fear in its workers, and partly due to the overall lack of spirit for organizing. Despite the failure of these drives, they offer a revealing example of the convergence of civil rights and workers rights, highlighting both the status of the civil rights movement in Durham and the difficulty of instigating grassroots-level change in a corporation the size of Duke Hospital, not to mention the larger Duke University community.

Regina Victoria Polk was an American labor leader and an activist for women workers in Chicago during the 1970s and 1980s. She was first an organizer and then a business agent for Local 743, the largest local in the International Brotherhood of Teamsters at that time. Throughout her career, she campaigned to organize and then represent clerical workers in predominantly female workplaces.

Shelton Tappes was an American labor organizer and civil rights activist, known for his role in drafting and negotiating the anti-discrimination clause included in the first contract between Ford Motor Company and the United Auto Workers (UAW.)