The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) is a United States federal law passed by the 104th United States Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton. It defines marriage for federal purposes as the union of one man and one woman, and allows states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages granted under the laws of other states. All of the act's provisions, except those relating to its short title, were ruled unconstitutional or left effectively unenforceable by Supreme Court decisions in the cases of United States v. Windsor (2013) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which means the law itself has been practically overturned.

The availability of legally recognized same-sex marriage in the United States expanded from one state (Massachusetts) in 2004 to all fifty states in 2015 through various court rulings, state legislation, and direct popular votes. States each have separate marriage laws, which must adhere to rulings by the Supreme Court of the United States that recognize marriage as a fundamental right guaranteed by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as first established in the 1967 landmark civil rights case of Loving v. Virginia.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 1982.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 1985.

Same-sex marriage is legal in the U.S. state of California. The state first issued marriage licenses to same-sex couples June 16, 2008 as a result of the Supreme Court of California finding in In re Marriage Cases that barring same-sex couples from marriage violated the state's Constitution. The issuance of such licenses was halted from November 5, 2008 through June 27, 2013 due to the passage of Proposition 8—a state constitutional amendment barring same-sex marriages. The granting of same-sex marriages recommenced following the United States Supreme Court decision in Hollingsworth v. Perry, which restored the effect of a federal district court ruling that overturned Proposition 8 as unconstitutional.

Marriage in the United States is a legal, social, and religious institution. The marriage age in the United States is set by each state and territory, either by statute or the common law applies. An individual can marry in the United States as of right, without parental consent or other authorisation, on reaching 18 years of age in all states except in Nebraska, where the general marriage age is 19, and Mississippi where the general marriage age is 21. In Puerto Rico the general marriage age is also 21. In all these jurisdictions, these are also the ages of majority. In Alabama, however, the age of majority is 19, while the general marriage age is 18. Most states also set a lower age at which underage persons are able to marry with parental and/or judicial consent. Marriages where one partner is less than 18 years of age are commonly referred to as child or underage marriages.

Immigration equality is a citizens' equal ability or right to immigrate their family members. It also applies to fair and equal execution of the laws and the rights of non-citizens regardless of nationality or where they are coming from. Immigration issues can also be a LGBT rights issue, as government recognition of same-sex relationships vary from country to country.

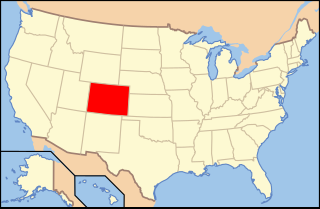

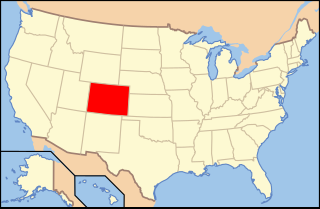

Same-sex marriage in Colorado has been legally recognized since October 7, 2014. Colorado's state constitutional ban on same-sex marriage was struck down in state district court on July 9, 2014, and by the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado on July 23, 2014. The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals had already made similar rulings with respect to such bans in Utah on June 25 and Oklahoma on July 18, which are binding precedents on courts in Colorado.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. United States Department of Health and Human Services 682 F.3d 1 is a United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit decision that affirmed the judgment of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), the section that defines the terms "marriage" as "a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife" and "spouse" as "a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or a wife." Both courts found DOMA to be unconstitutional, though for different reasons. The trial court held that DOMA violates the Tenth Amendment and Spending Clause. In a companion case, Gill v. Office of Personnel Management, the same judge held that DOMA violates the Equal Protection Clause. On May 31, 2012, the First Circuit held the act violates the Equal Protection Clause, while federalism concerns affect the equal protection analysis, DOMA does not violate the Spending Clause or Tenth Amendment.

Gill et al. v. Office of Personnel Management, 682 F.3d 1 is a United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit decision that affirmed the judgment of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), the section that defines the term "marriage" as "a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife" and "spouse" as "a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or a wife."

Diaz v. Brewer, originally Collins v. Brewer No. 2:09-cv-02402-JWS (Az.Dist.Ct.), is a lawsuit heard on appeal by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which affirmed a lower court's issuance of a preliminary injunction that prevented Arizona from implementing its 2009 statute that would have terminated the eligibility for healthcare benefits of any state employee's same-sex domestic partner.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Colorado enjoy the same rights as non-LGBT people. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Colorado since 1972. Same-sex marriage has been recognized since October 2014, and the state enacted civil unions in 2013, which provide some of the rights and benefits of marriage. State law also prohibits discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations and the use of conversion therapy on minors. In July 2020, Colorado became the 11th US state to abolish the gay panic defense.

Pedersen v. Office of Personnel Management is a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act, Section 3, which defined the federal definition of marriage to be a union of a man and a woman, entirely excluding legally married same-sex couples. The District Court that originally heard the case ruled Section 3 unconstitutional. On June 26, 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled Section 3 of DOMA unconstitutional, and denied appeal of Pedersen the next day.

United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 (2013), is a landmark United States Supreme Court civil rights case concerning same-sex marriage. The Court held that Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which denied federal recognition of same-sex marriages, was a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Golinski v. Office of Personnel Management, 824 F. Supp. 2d 968, was a lawsuit filed in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California. The plaintiff, Karen Golinski, challenged the constitutionality of section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined, for the purposes of federal law, marriage as being between one man and one woman, and spouse as a husband or wife of the opposite sex.

This article contains a timeline of significant events regarding same-sex marriage in the United States. On June 26, 2015, the landmark US Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges effectively ended restrictions on same-sex marriage in the United States.

Cardona v. Shinseki was an appeal brought in the United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims (CAVC) of a decision by the Board of Veterans' Appeals upholding the denial of service-connected disability benefits for the dependent wife of a female veteran. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs denied the disability benefits based on the definition of "spouse" as "a person of the opposite sex" under federal statute. On March 11, 2014, the CAVC dismissed the case as moot after the Secretary of Veterans Affairs advised the Court that he would neither defend nor enforce the federal statute. Cardona subsequently received full payment of her spousal benefits, retroactive to her date of application.

Richard Frank Adams was a Filipino-American gay rights activist. After his 1975 same-sex marriage was declared invalid for the purposes of granting his husband permanent residency, Adams filed the federal lawsuit Adams v. Howerton. This was the first lawsuit in America to seek recognition of a same-sex marriage by the federal government.

Same-sex immigration policy in the United States denied couples in same-sex relationships the same rights and privileges afforded different-sex couples based on several court decisions and the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Section 3 of DOMA unconstitutional in United States v. Windsor on June 26, 2013.

Kitchen v. Herbert, 961 F.Supp.2d 1181, affirmed, 755 F.3d 1193 ; stay granted, 134 S.Ct. 893 (2014); petition for certiorari denied, No. 14-124, 2014 WL 3841263, is the federal case that successfully challenged Utah's constitutional ban on marriage for same-sex couples and similar statutes. Three same-sex couples filed suit in March 2013, naming as defendants Utah Governor Gary R. Herbert, Attorney General John Swallow, and Salt Lake County Clerk Sherrie Swensen in their official capacities.