Related Research Articles

The censor was a magistrate in ancient Rome who was responsible for maintaining the census, supervising public morality, and overseeing certain aspects of the government's finances.

The Gracchi brothers were two Roman brothers, sons of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus who was consul in 177 BC. Tiberius, the elder brother, was tribune of the plebs in 133 BC and Gaius, the younger brother, was tribune a decade later in 123–122 BC.

Tribune was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the authority of the senate and the annual magistrates, holding the power of ius intercessionis to intervene on behalf of the plebeians, and veto unfavourable legislation. There were also military tribunes, who commanded portions of the Roman army, subordinate to higher magistrates, such as the consuls and praetors, promagistrates, and their legates. Various officers within the Roman army were also known as tribunes. The title was also used for several other positions and classes in the course of Roman history.

An augur was a priest and official in the classical Roman world. His main role was the practice of augury, the interpretation of the will of the gods by studying events he observed within a predetermined sacred space (templum). The templum corresponded to the heavenly space above. The augur's decisions were based on what he personally saw or heard from within the templum; they included thunder, lightning and any accidental signs such as falling objects, but in particular, birdsigns; whether the birds he saw flew in groups or alone, what noises they made as they flew, the direction of flight, what kind of birds they were, how many there were, or how they fed. This practice was known as "taking the auspices". As circumstance did not always favour the convenient appearance of wild birds or weather phenomena, domesticated chickens kept for the purpose were sometimes released into the templum, where their behviour, particularly how they fed, could be studied by the augur.

Praetor, also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected magistratus (magistrate), assigned to discharge various duties. The functions of the magistracy, the praetura (praetorship), are described by the adjective: the praetoria potestas, the praetorium imperium, and the praetorium ius, the legal precedents established by the praetores (praetors). Praetorium, as a substantive, denoted the location from which the praetor exercised his authority, either the headquarters of his castra, the courthouse (tribunal) of his judiciary, or the city hall of his provincial governorship.

In antiquity, publicans were public contractors, in whose official capacity they often supplied the Roman legions and military, managed the collection of port duties, and oversaw public building projects. In addition, they served as tax collectors for the Roman Republic, farming the taxes of the Roman provinces, and bidding on contracts for the collection of various types of taxes. Importantly, this role as tax collectors was not emphasized until late into the history of the Republic. The publicans were usually of the class of equites.

The patricians were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom, and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after the Conflict of the Orders. By the time of the late Republic and Empire, membership in the patriciate was of only nominal significance.

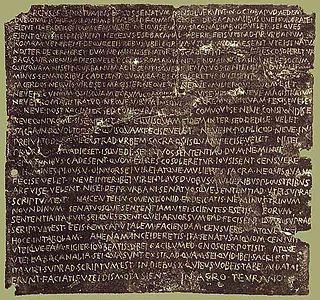

The senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus is a notable Old Latin inscription dating to 186 BC. It was discovered in 1640 at Tiriolo, in Calabria, southern Italy. Published by the presiding praetor, it conveys the substance of a decree of the Roman Senate prohibiting the Bacchanalia throughout all Italy, except in certain special cases which must be approved specifically by the Senate.

The equites constituted the second of the property-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an eques.

Optimates and populares are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated academic discussion" as to whether Romans would have recognised an ideological content or political split in the label.

Aerarium, from aes + -ārium, was the name given in Ancient Rome to the public treasury, and in a secondary sense to the public finances.

Ubi sunt is a rhetorical question taken from the Latin Ubi sunt qui ante nos fuerunt?, meaning "Where are those who were before us?" Ubi nunc...? is a common variant.

A lex Julia was an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the gens Julia. Most often, "Julian laws", lex Julia or leges Juliae refer to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 BC, or to a law related to Julius Caesar.

A tribus, or tribe, was a division of the Roman people for military, censorial, and voting purposes. When constituted in the comitia tributa, the tribes were the voting units of a legislative assembly of the Roman Republic.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of uncodified norms and customs which, together with various written laws, guided the procedural governance of the Roman Republic. The constitution emerged from that of the Roman kingdom, evolved substantively and significantly—almost to the point of unrecognisability—over the almost five hundred years of the republic. The collapse of republican government and norms from 133 BC would lead to the rise of Augustus and his principate.

The Roman Senate was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome. It survived the overthrow of the Roman monarchy in 509 BC; the fall of the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC; the division of the Roman Empire in AD 395; and the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476; Justinian's attempted reconquest of the west in the 6th century, and lasted well into the Eastern Roman Empire's history.

The history of the Constitution of the Roman Republic is a study of the ancient Roman Republic that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC until the founding of the Roman Empire in 27 BC. The constitutional history of the Roman Republic can be divided into five phases. The first phase began with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Kingdom in 509 BC, and the final phase ended with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Republic, and thus created the Roman Empire, in 27 BC. Throughout the history of the Republic, the constitutional evolution was driven by the struggle between the aristocracy and the ordinary citizens.

Manius Valerius Maximus was Roman dictator in 494 BC during the first secession of the plebs. His brothers were Publius Valerius Publicola and Marcus Valerius Volusus. They were said to be the sons of Volesus Valerius.

A maenianum was a balcony or gallery for spectators at a public show in ancient Rome. The name was originally given by censor Gaius Maenius in 318 BC to the decorated gallery in the Colosseum, where spectators watched gladiatorial combats.

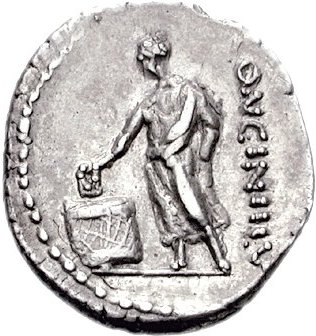

Elections in the Roman Republic were an essential part of its governance, with participation only being afforded to Roman citizens. Upper-class interests, centered in the urban political environment of cities, often trumped the concerns of the diverse and disunified lower class; while at times, the people already in power would pre-select candidates for office, further reducing the value of voters’ input. The candidates themselves at first remained distant from voters and refrained from public presentations, but they later more than made up for time lost with habitual bribery, coercion, and empty promises. As the practice of electoral campaigning grew in use and extent, the pool of candidates was no longer limited to a select group with riches and high birth. Instead, many more ordinary citizens had a chance to run for office, allowing for more equal representation in key government decisions.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Smith, William, ed. (1870). "adlecti". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities . London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Smith, William, ed. (1870). "adlecti". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities . London: John Murray.