Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important centre of Celtic Christianity under Saints Aidan, Cuthbert, Eadfrith, and Eadberht of Lindisfarne. The island was originally home to a monastery, which was destroyed during the Viking invasions but re-established as a priory following the Norman Conquest of England. Other notable sites built on the island are St Mary the Virgin parish church, Lindisfarne Castle, several lighthouses and other navigational markers, and a complex network of lime kilns. In the present day, the island is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and a hotspot for historical tourism and bird watching. As of February 2020, the island had three pubs, a hotel and a post office.

Ninian is a Christian saint, first mentioned in the 8th century as being an early missionary among the Pictish peoples of what is now Scotland. For this reason he is known as the Apostle to the Southern Picts, and there are numerous dedications to him in those parts of Scotland with a Pictish heritage, throughout the Scottish Lowlands, and in parts of Northern England with a Northumbrian heritage. He is also known as Ringan in Scotland, and as Trynnian in Northern England.

Pittenweem Priory was an Augustinian priory located in the village of Pittenweem, Fife, Scotland.

The Isle of May is located in the north of the outer Firth of Forth, approximately 8 km (5.0 mi) off the coast of mainland Scotland. It is about 1.5 kilometres long and 0.5 kilometres wide. The island is owned and managed by NatureScot as a national nature reserve. There are now no permanent residents, but the island was the site of St Adrian's Priory during the Middle Ages.

Saint Fillan was a sixth-century Scottish monk active in Fife. His feast day is 20 June.

Iona Abbey is an abbey located on the island of Iona, just off the Isle of Mull on the West Coast of Scotland.

The Abbey of Saint Mary of Crossraguel is a ruin of a former abbey near the town of Maybole, South Ayrshire, Scotland. Although it is a ruin, visitors can still see the original monks’ church, their cloister and their dovecot.

Christianity in medieval Scotland includes all aspects of Christianity in the modern borders of Scotland in the Middle Ages. Christianity was probably introduced to what is now Lowland Scotland by Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia. After the collapse of Roman authority in the fifth century, Christianity is presumed to have survived among the British enclaves in the south of what is now Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced. Scotland was largely converted by Irish missions associated with figures such as St Columba, from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions founded monastic institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas. Scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbots were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed and there were significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century. After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland in the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.

Whithorn Priory was a medieval Scottish monastery that also served as a cathedral, located at 6 Bruce Street in Whithorn, Wigtownshire, Dumfries and Galloway.

March 3 - Eastern Orthodox liturgical calendar - March 5

Saint William of Perth, also known as Saint William of Rochester was a Scottish saint who was martyred in England. He is the patron saint of adopted children. Following his death, he gained local acclaim and was canonised by Pope Alexander IV in 1256.

St Andrews Cathedral Priory was a priory of Augustinian canons in St Andrews, Fife, Scotland. It was one of the great religious houses in Scotland, and instrumental in the founding of the University of St Andrews.

The Isle of May Priory was a monastery and community of Benedictine monks established for 9 monks of Reading Abbey on the Isle of May in the Firth of Forth, Scotland, in 1153, under the patronage of David I of Scotland. The priory passed into the control of St Andrews Cathedral Priory in the later 13th century, and in 1318 the community relocated to Pittenweem Priory on the Fife coast.

Sir Andrew Wood of Largo was a Scottish sea captain. Beginning as a merchant in Leith, he was involved in national naval actions and rose to become Lord High Admiral of Scotland. He was knighted c. 1495. He may have transported James III across the Firth of Forth to escape the rebels in 1488.

Whitekirk is a small settlement in East Lothian, Scotland. Together with the nearby settlement of Tyninghame, it gives its name to the parish of Whitekirk and Tyninghame.

The Christianisation of Scotland was the process by which Christianity spread in what is now Scotland, which took place principally between the fifth and tenth centuries.

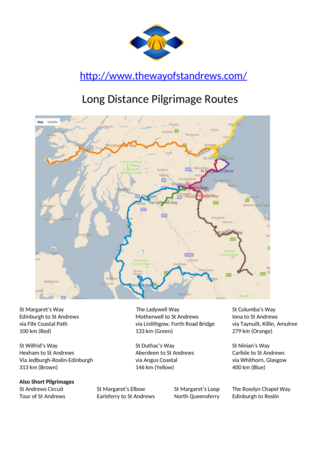

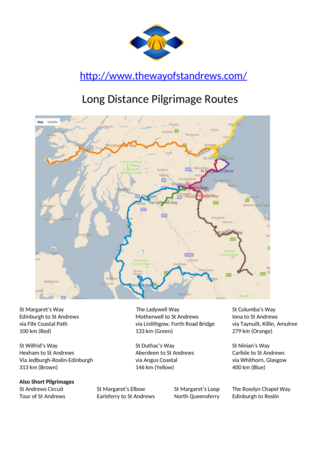

The Way of St Andrews is a Christian pilgrimage to St Andrews Cathedral in Fife, on the east coast of Scotland, UK, where the relics of the apostle, Saint Andrew, were once kept. A group started a revival in 2012 introducing new routes.

Ethernan was a 7th century Scottish martyr and saint. The focus of his cultus was the Isle of May.