Related Research Articles

Beginning on August 7, 1961, a series of social psychology experiments were conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram, who intended to measure the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts conflicting with their personal conscience. Participants were led to believe that they were assisting an unrelated experiment, in which they had to administer electric shocks to a "learner". These sham or fake electric shocks gradually increased to levels that would have been fatal had they been real.

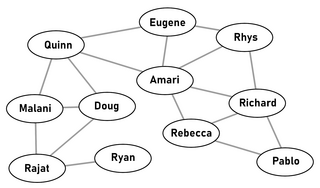

In the social sciences, a social group is defined as two or more people who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and collectively have a sense of unity. Regardless, social groups come in a myriad of sizes and varieties. For example, a society can be viewed as a large social group. The system of behaviors and psychological processes occurring within a social group or between social groups is known as group dynamics.

The Stanford prison experiment (SPE) was a psychological experiment conducted in August 1971. It was a two-week simulation of a prison environment that examined the effects of situational variables on participants' reactions and behaviors. Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo led the research team who administered the study.

The out-group homogeneity effect is the perception of out-group members as more similar to one another than are in-group members, e.g. "they are alike; we are diverse". Perceivers tend to have impressions about the diversity or variability of group members around those central tendencies or typical attributes of those group members. Thus, outgroup stereotypicality judgments are overestimated, supporting the view that out-group stereotypes are overgeneralizations. The term "outgroup homogeneity effect", "outgroup homogeneity bias" or "relative outgroup homogeneity" have been explicitly contrasted with "outgroup homogeneity" in general, the latter referring to perceived outgroup variability unrelated to perceptions of the ingroup.

In psychology, the Asch conformity experiments or the Asch paradigm were a series of studies directed by Solomon Asch studying if and how individuals yielded to or defied a majority group and the effect of such influences on beliefs and opinions.

Self-sacrifice is the giving up of something that a person wants for themselves so that others can be helped or protected or so that other external values can be advanced or protected. Generally, the act of self-sacrifice conforms to the rule that it does not serve the person’s best self-interest and will leave the person in a worse situation than the person otherwise would have been.

System justification theory is a theory within social psychology that system-justifying beliefs serve a psychologically palliative function. It proposes that people have several underlying needs, which vary from individual to individual, that can be satisfied by the defense and justification of the status quo, even when the system may be disadvantageous to certain people. People have epistemic, existential, and relational needs that are met by and manifest as ideological support for the prevailing structure of social, economic, and political norms. Need for order and stability, and thus resistance to change or alternatives, for example, can be a motivator for individuals to see the status quo as good, legitimate, and even desirable.

The Experiment is a 2002 BBC documentary series in which 15 men are randomly selected to be either "prisoner" or guard, contained in a simulated prison over an eight-day period. Produced by Steve Reicher and Alex Haslam, it presents the findings of what has subsequently become known as the BBC Prison Study. These findings centered around "the social and psychological consequences of putting people in groups of unequal power" and "when people accept inequality and when they challenge it".

The minimal group paradigm is a method employed in social psychology. Although it may be used for a variety of purposes, it is best known as a method for investigating the minimal conditions required for discrimination to occur between groups. Experiments using this approach have revealed that even arbitrary distinctions between groups, such as preferences for certain paintings, or the color of their shirts, can trigger a tendency to favor one's own group at the expense of others, even when it means sacrificing in-group gain.

Social identity is the portion of an individual's self-concept derived from perceived membership in a relevant social group.

Stephen David Reicher is Bishop Wardlaw Professor of Social Psychology at the University of St Andrews.

Optimal distinctiveness is a social psychological theory seeking to understand ingroup–outgroup differences. It asserts that individuals desire to attain an optimal balance of inclusion and distinctiveness within and between social groups and situations. These two motives are in constant opposition with each other; when there is too much of one motive, the other must increase in order to counterbalance it and vice versa. The theory of optimal distinctiveness was first proposed by Dr. Marilynn B. Brewer in 1991 and extensively reviewed in 2010 by Drs. Geoffrey J. Leonardelli, Cynthia L. Pickett, and Marilynn Brewer.

The social identity model of deindividuation effects is a theory developed in social psychology and communication studies. SIDE explains the effects of anonymity and identifiability on group behavior. It has become one of several theories of technology that describe social effects of computer-mediated communication.

Self-categorization theory is a theory in social psychology that describes the circumstances under which a person will perceive collections of people as a group, as well as the consequences of perceiving people in group terms. Although the theory is often introduced as an explanation of psychological group formation, it is more accurately thought of as general analysis of the functioning of categorization processes in social perception and interaction that speaks to issues of individual identity as much as group phenomena. It was developed by John Turner and colleagues, and along with social identity theory it is a constituent part of the social identity approach. It was in part developed to address questions that arose in response to social identity theory about the mechanistic underpinnings of social identification.

Rolf van Dick is a German social psychologist.

"Social identity approach" is an umbrella term designed to show that there are two methods used by academics to describe certain complex social phenomena- namely the dynamics between groups and individuals. Those two theoretical methods are called social identity theory and self-categorization theory. Experts describe them as two intertwined, but distinct, social psychological theories. The term "social identity approach" arose as an attempt to mitigate against the tendency to conflate the two theories, as well as the tendency to mistakenly believe one theory to be a component of the other. These theories should be thought of as overlapping. While there are similarities, self categorisation theory has greater explanatory scope and has been investigated in a broader range of empirical conditions. Self-categorization theory can also be thought of as developed to address limitations of social identity theory. Specifically the limited manner in which social identity theory deals with the cognitive processes that underpin the behaviour it describes. Although this term may be useful when contrasting broad social psychological movements, when applying either theory it is thought of as beneficial to distinguish carefully between the two theories in such a way that their specific characteristics can be retained.

In social psychology, collective narcissism is the tendency to exaggerate the positive image and importance of a group to which one belongs. The group may be defined by ideology, race, political beliefs/stance, religion, sexual orientation, social class, language, nationality, employment status, education level, cultural values, or any other ingroup. While the classic definition of narcissism focuses on the individual, collective narcissism extends this concept to similar excessively high opinions of a person's social group, and suggests that a group can function as a narcissistic entity.

Idiosyncrasy credit is a concept in social psychology that describes an individual's capacity to acceptably deviate from group expectations. Idiosyncrasy credits are increased (earned) each time an individual conforms to a group's expectations, and decreased (spent) each time an individual deviates from a group's expectations. Edwin Hollander originally defined idiosyncrasy credit as "an accumulation of positively disposed impressions residing in the perceptions of relevant others; it is… the degree to which an individual may deviate from the common expectancies of the group".

Followership are the actions of someone in a subordinate role. It may also be considered as particular services that can help the leader, a role within a hierarchical organization, a social construct that is integral to the leadership process, or the behaviors engaged in while interacting with leaders in an effort to meet organizational objectives. As such, followership is best defined as an intentional practice on the part of the subordinate to enhance the synergetic interchange between the follower and the leader.

Michelle K. Ryan is a Professor of Social and Organizational Psychology at the University of Exeter and (part-time) Professor of Diversity at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands.

References

- 1 2 3 "Professor Alex Haslam - UQ Researchers". University of Queensland. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ↑ "Robert T Jones Scholarship programme | University of St Andrews".

- ↑ Reicher, S. D., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 1–40.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2007). Beyond the banality of evil: Three dynamics of an interactionist social psychology of tyranny. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 615–622.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2012). When prisoners take over the prison: A social psychology of resistance. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16, 152–179.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2012). Contesting the 'nature' of conformity: What Milgram and Zimbardo's studies really show. PLoS Biology, 10(11), e1001426. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001426

- ↑ Reicher, S. D., Haslam, S. A., & Smith, J. R. (2012). Working towards the experimenter: Reconceptualizing obedience within the Milgram paradigm as identification-based followership. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 315–324.

- ↑ Turner, J. C., & Haslam, S. A. (2001). Social identity, organizations and leadership. In: M. E. Turner (Ed.), Groups at work: Advances in theory and research (pp. 25–65). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., & Platow, M. J. (2001). The link between leadership and followership: How affirming social identity translates vision into action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1469–1479.

- ↑ Hass, Nancy (18 July 2012). "Marissa Mayer Stares Down 'Glass Cliff' at Yahoo". The Daily Beast . Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ↑ Ryan, M. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2005). The Glass Cliff: Evidence that women are over-represented in precarious leadership positions. British Journal of Management, 16, 81–90.

- ↑ Ryan, M. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2007). The Glass Cliff: Exploring the dynamics surrounding the appointment of women precarious leadership positions. Academy of Management Review, 32, 549–572.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., & Ryan, M. K. (2008). The road to the glass cliff: Differences in the perceived suitability of men and women for leadership positions in succeeding and failing organizations. Leadership Quarterly, 19, 530–546.

- ↑ Jetten, J., Haslam, C., & Haslam, S. A. (Eds.) (2012). The social cure: Identity, health and well-being. New York and Hove: Psychology Press.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2009). Social identity, health and well-being: An emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 58, 1–23.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2006). Stressing the group: Social identity and the unfolding dynamics of responses to stress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1037–1052.

- ↑ Haslam, S. A., O'Brien, A., Jetten, J., Vormedal, K., & Penna, S. (2005). Taking the strain: Social identity, social support and the experience of stress. 'British Journal of Social Psychology', '44', 355–370.

- ↑ "UQ equal tops in nation for ARC Australia Laureate Fellowships". University of Queensland . 10 August 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Australia Day Honours List" (PDF). The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.