The Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) is a public medical school in Charleston, South Carolina. It opened in 1824 as a small private college aimed at training physicians and has since established hospitals and medical facilities across the state. It is one of the oldest continually operating schools of medicine in the United States and the oldest in the Deep South.

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) is a health science university of the U.S. federal government. The primary mission of the school is to prepare graduates for service to the U.S. at home and abroad as uniformed health professionals, scientists and leaders; by conducting cutting-edge, military-relevant research; by leading the Military Health System in key functional and intellectual areas; and by providing operational support to units around the world.

A hospital corpsman is an enlisted medical specialist of the United States Navy, who may also serve in a U.S. Marine Corps unit. The corresponding rating within the United States Coast Guard is health services technician (HS).

William Longshaw Jr. was a physician who volunteered for service in the United States Union Navy during the American Civil War. Longshaw obtained medical and pharmacy training in Boston, New York City, and New Orleans, receiving his medical degree from the University of Michigan. He was appointed acting assistant surgeon by the navy in 1862, serving aboard USS Yankee, Passaic, Penobscot, Lehigh, and finally his squadron's flagship Minnesota.

The United States Air Force Medical Service (AFMS) consists of the five distinct medical corps of the Air Force and enlisted medical technicians. The AFMS was created in 1949 after the newly independent Air Force's first Surgeon General, Maj. General Malcolm C. Grow (1887–1960), convinced the United States Army and President Harry S. Truman that the Air Force needed its own medical service.

Leonard Hall is a historic educational building located on the campus of Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. Built in 1881 and originally named Leonard Medical Center, it became known as Leonard Medical School, and then Leonard Hall. It was established when medical schools were professionalizing and was the first medical school in the United States to offer a four-year curriculum. It was also the first four-year medical school that African Americans could attend.

The Charlestown Female Seminary, was a private Christian school for wealthy white girls in Charleston, South Carolina, United States. Opened in 1830, the female seminary was the second school in Charlestown for young women.

Henry McKee Minton was an African-American medical doctor who was one of the founders of Sigma Pi Phi and was Superintendent of the Mercy Hospital of Philadelphia for twenty-four years.

James Henry Conyers, on September 21, 1872 was the first African-American person admitted to the United States Naval Academy.

Frazier B. Baker was an African-American teacher who was appointed as postmaster of Lake City, South Carolina in 1897 under the William McKinley administration. He and his infant daughter Julia Baker died at his house after being fatally shot during a white mob attack on February 22, 1898. The mob set the house on fire to force the family out. His wife and two of his other five children were wounded, but escaped the burning house and mob, and survived.

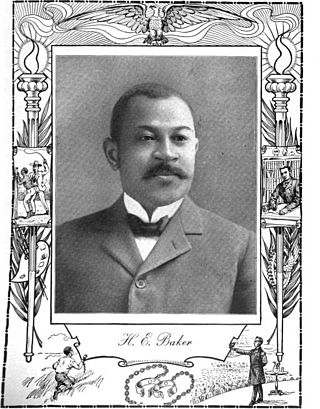

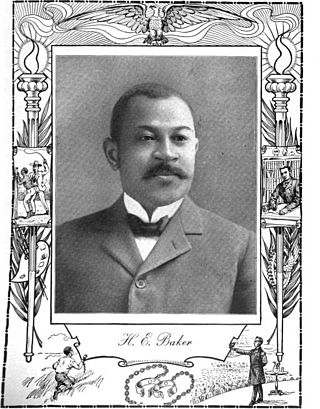

Henry Edwin Baker Jr. was the third African American to enter the United States Naval Academy. He later served as an assistant patent examiner in the United States Patent Office, where he would chronicle the history of African-American inventors.

Alice Woodby McKane was the first woman to work as a medical doctor in Savannah, Georgia. She was not only known as a physician but also as a politician and an author. She and her husband Cornelius McKane contributed an important part in medical history. She opened the first school of nurse training for black people in Savannah. She also helped her husband to make his dream which was opening the Hospital in Liberia come true. After returning from Liberia, they established the MCKane Hospital for Women and Children and later was known as Charity Hospital to treat for all people in Savannah, especially for African American people.

Flint-Goodridge Hospital was a hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana. For almost a century (1896–1983) it served predominantly African-American patients and was the first black hospital in the South. For most of these years, was owned and operated by Dillard University, a historically black university. From 1932 until its closing in 1983 it was located on Louisiana Avenue in uptown New Orleans. Its former Louisiana Avenue facility is now listed in the US National Register of Historic Places.

Lucy Hughes Brown was the first African-American woman physician licensed to practice in both North Carolina and South Carolina and the cofounder of a nursing school and hospital. Hughes Brown was also an activist and poet.

Anna DeCosta Banks was employed at the Hospital and Training School for Nurses in Charleston, South Carolina, where she was the first head nurse. Banks is known for her nursing career, as well as a later position held as superintendent for 32 years at the same training school for nurses. Specifically designed for women of color, this hospital was later renamed McClennan-Banks Memorial Hospital in her honor.

Samuel Benjamin Thompson was a lawyer, judicial official, and Reconstruction Era politician in South Carolina.

William Demosthenes Crum, alternatively known as William Demos Crum, was an African American physician and diplomat.

The Dr. Cyril O. Spann Medical Office, located in Columbia, South Carolina, served African-American patients during de jure and de facto racial segregation in the United States. Built in 1963, it was added to United States National Register of Historic Places on May 20, 2019.

Wallingford Academy was a school for "Colored" children in Charleston, South Carolina. It was organized by Jonathan C. Gibbs a minister with the Zion Presbyterian Church and opened in 1865. David Brown, a clergyman and teacher moved to Charleston with his wife Hughes Brown to serve as principal.