Related Research Articles

Alger Hiss was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in connection with this charge in 1950. Before the trial, Hiss was involved in the establishment of the United Nations, both as a US State Department official and as a UN official. In later life, he worked as a lecturer and author.

The United States Senate's Special Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, 1951–77, known more commonly as the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) and sometimes the McCarran Committee, was authorized by S. 366, approved December 21, 1950, to study and investigate (1) the administration, operation, and enforcement of the Internal Security Act of 1950 and other laws relating to espionage, sabotage, and the protection of the internal security of the United States and (2) the extent, nature, and effects of subversive activities in the United States "including, but not limited to, espionage, sabotage, and infiltration of persons who are or may be under the domination of the foreign government or organization controlling the world Communist movement or any movement seeking to overthrow the Government of the United States by force and violence". The resolution also authorized the subcommittee to subpoena witnesses and require the production of documents. Because of the nature of its investigations, the subcommittee is considered by some to be the Senate equivalent to the older House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

Owen Lattimore was an American Orientalist and writer. He was an influential scholar of China and Central Asia, especially Mongolia. Although he never earned a college degree, in the 1930s he was editor of Pacific Affairs, a journal published by the Institute of Pacific Relations, and taught at Johns Hopkins University from 1938 to 1963. He was director of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations from 1939 to 1953. During World War II, he was an advisor to Chiang Kai-shek and the American government and contributed extensively to the public debate on U.S. policy toward Asia. From 1963 to 1970, Lattimore was the first Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of Leeds in England.

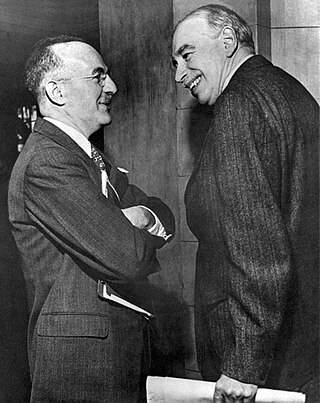

Harry Dexter White was a senior U.S. Treasury department official. Working closely with the Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., he helped set American financial policy toward the Allies of World War II. He was later accused of espionage by passing information to the Soviet Union, an allegation which was confirmed after his death.

Joseph Milton Bernstein was an American accused of spying for the Soviet Union and later confirmed as a Soviet agent by the US intelligence program Venona.

Solomon Adler worked as U.S. Treasury representative in China during World War II.

William Perl (1920–1970), whose original name was William Mutterperl, was an American physicist and Soviet spy.

Elizabeth Terrill Bentley was an American NKVD spymaster, who was recruited from within the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). She served the Soviet Union as the primary handler of multiple highly placed moles within both the United States Federal Government and the Office of Strategic Services from 1938 to 1945. She defected by contacting the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and debriefing about her espionage activities.

Virginius Frank Coe was a United States government official who was identified by Soviet defectors Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers as being an underground member of the Communist Party and as belonging to the Soviet spy group known as the Silvermaster ring.

Maurice Hyman Halperin (1906–1995) was an American writer, professor, diplomat, and accused Soviet spy.

The Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) was an international NGO established in 1925 to provide a forum for discussion of problems and relations between nations of the Pacific Rim. The International Secretariat, the center of most IPR activity over the years, consisted of professional staff members who recommended policy to the Pacific Council and administered the international program. The various national councils were responsible for national, regional and local programming. Most participants were members of the business and academic communities in their respective countries. Funding came largely from businesses and philanthropies, especially the Rockefeller Foundation. IPR international headquarters were in Honolulu until the early 1930s when they were moved to New York and the American Council emerged as the dominant national council.

David Harold Karr, born David Katz was a controversial American journalist, businessman, Communist and NKVD agent.

Clarence Francis Hiskey (1912–1998), born Clarence Szczechowski, was a scientist who worked on the Manhattan Project and was identified as Soviet espionage agent. He became active in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) when he attended graduate school at the University of Wisconsin.

John Stewart Service was an American diplomat who served in the Foreign Service in China prior to and during World War II. Considered one of the State Department's "China Hands," he was an important member of the Dixie Mission to Yan'an. Service correctly predicted that the Communists would defeat the Nationalists in a civil war. He and other diplomats were blamed for the "loss" of China in the domestic political turmoil after the 1949 Communist triumph in China. In June 1945, Service was arrested in the Amerasia Affair in 1945. The prosecution sought an indictment for espionage, but a federal grand jury unanimously declined to indict him.

Robert Emmet Lee was a 20th-century American government official, best known as Commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission from 1953 to 1981, including Interim FCC Chairman and Chairman.

Andrew Roth was a biographer and journalist known for his compilation of Parliamentary Profiles, a directory of biographies of British Members of Parliament, a small sample of which is available online in The Guardian. Active amongst the politicians and journalists in Westminster for sixty years, he also made appearances on British television. He first gained prominence when arrested in 1945 as one of six suspects in the Amerasia spy case.

Frederick Vanderbilt Field was an American leftist political activist, political writer and a great-great-grandson of railroad tycoon Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt, disinherited by his wealthy relatives for his radical political views. Field became a specialist on Asia and was a prime staff member and supporter of the Institute of Pacific Relations. He also supported Henry Wallace's Progressive Party and so many openly Communist organizations that he was accused of being a member of the Communist Party. He was a top target of the American government during the peak of 1950s McCarthyism. Field denied ever having been a party member but admitted in his memoirs, "I suppose I was what the Party called a 'member at large.'"

Mark Gayn, born Mark Julius Ginsbourg was an American and Canadian journalist, who worked for The Toronto Star for 30 years.

Philip Jacob Jaffe was a communist American businessman, editor and author. He was born in Ukraine and moved to New York City as a child. He became the owner of a profitable greeting card company. In the 1930s Jaffe became interested in Communism and edited two journals associated with the Communist Party USA. He is known for the 1945 Amerasia affair, in which the FBI found classified documents in the offices of his Amerasia magazine that had been given to him by State Department employee John S. Service. He received a minimal sentence due to OSS/FBI bungling of the investigation, but there were continued reviews of the affair by Congress into the 1950s. He later wrote about the rise and decline of the Communist Party in the USA.

References

- ↑ "Frederick Vanderbilt Field". The Guardian . February 16, 2000. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ↑ FBI Report: Institute of Pacific Relations, Internal Security – C, November 4, 1944 (FBI file: Institute of Pacific Relations, Section 1, PDF p. 45)

- 1 2 Klehr, Harvey; Radosh, Ronald (1996). The Amerasia Spy Case: Prelude to McCarthyism. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 3 (cost), 44 (Mitchell), 45–6 (Roth). ISBN 978-0807822456 . Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ Yuwu Song (July 18, 2006). Encyclopedia of Chinese-American Relations. McFarland. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-7864-9164-3 . Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ↑ Klehr and Radosh, The Amerasia Spy Case, 28ff.

- ↑ Klehr and Radosh, The Amerasia Spy Case, 50ff.

- ↑ Report of the United States Senate Subcommittee on the Investigation of Loyalty of State Department Employees, 1950, appendix, p. 2051.

- ↑ FBI Amerasia file, Section 52.

- ↑ New York Times: "FBI Seizes 6 as Spies, Two in State Dept.", June 7, 1945, accessed April 19, 2011

- ↑ Robert P. Newman, The Cold War Romance of Lillian Helman and John Melby (University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 68

- ↑ "The Strange Case of Amerasia | Whittaker Chambers". whittakerchambers.org. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- ↑ M. Stanton Evans, McCarthyism: Waging the Cold War in America Archived 2012-04-15 at the Wayback Machine , Human Events, May 8, 2003.