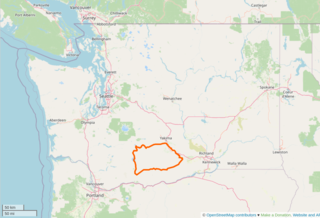

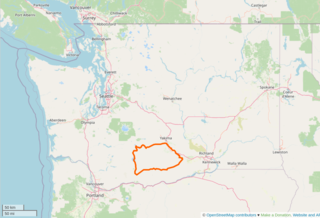

The Yakama are a Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in eastern Washington state.

The Yakama Indian Reservation is a Native American reservation in Washington state of the federally recognized tribe known as the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. The tribe is made up of Klikitat, Palus, Wallawalla, Wenatchi, Wishram, and Yakama peoples.

Chief Leschi was a chief of the Nisqually Indian Tribe of southern Puget Sound, Washington, primarily in the area of the Nisqually River.

The history of Washington includes thousands of years of Native American history before Europeans arrived and began to establish territorial claims. The region was part of Oregon Territory from 1848 to 1853, after which it was separated from Oregon and established as Washington Territory following the efforts at the Monticello Convention. On November 11, 1889, Washington became the 42nd state of the United States.

The Yakima War (1855–1858), also referred to as the Plateau War or Yakima Indian War, was a conflict between the United States and the Yakama, a Sahaptian-speaking people of the Northwest Plateau, then part of Washington Territory, and the tribal allies of each. It primarily took place in the southern interior of present-day Washington. Isolated battles in western Washington and the northern Inland Empire are sometimes separately referred to as the Puget Sound War and the Coeur d'Alene War, respectively.

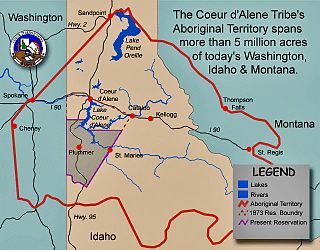

The Battle of Four Lakes was a battle during the Coeur d'Alene War of 1858 in the Washington Territory in the United States. The Coeur d'Alene War was part of the Yakima War, which began in 1855. The battle was fought near present-day Four Lakes, Washington, between elements of the United States Army and a coalition of Native American tribes consisting of Schitsu'umsh, Palus, Spokan, and Yakama warriors.

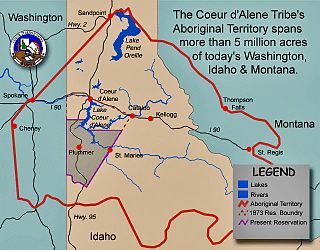

The Coeur d'Alene War of 1858, also known as the Spokane-Coeur d'Alene-Pend d'oreille-Paloos War, was the second phase of the Yakima War, involving a series of encounters between the allied Native American tribes of the Skitswish, Kalispell, Spokane, Palouse and Northern Paiute against United States Army forces in Washington and Idaho.

Kamiakin (Yakama) was a leader of the Yakama, Palouse, and Klickitat peoples east of the Cascade Mountains in what is now southeastern Washington state. In 1855, he was disturbed by threats of the Territorial Governor, Isaac Stevens, against the tribes of the Columbia Plateau. After being forced to sign a treaty of land cessions, Kamiakin organized alliances with 14 other tribes and leaders, and led the Yakima War of 1855–1858.

Qualchan was a 19th-century Yakama chieftain who participated in the Yakama War with his Uncle Kamiakin and other chieftains.

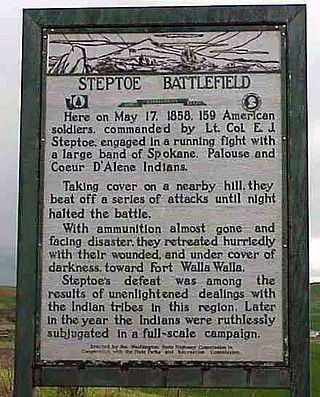

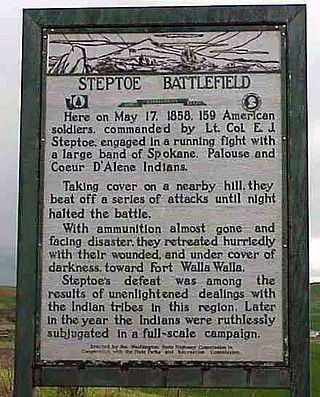

The Battle of Pine Creek, also known as the Battle of Tohotonimme and the Steptoe Disaster, was a conflict between United States Army forces under Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe and members of the Coeur d'Alene, Palouse and Spokane Native American tribes. It took place on May 17, 1858, near what is present-day Rosalia, Washington. The Native Americans were victorious.

Absalom Jefferson Hembree was an American soldier and politician in what became the state of Oregon. A native of Tennessee, he served in the Provisional Legislature of Oregon and the Oregon Territorial Legislature before being killed in action during the Yakima War.

Lucullus Virgil McWhorter was an American farmer and frontiersman who documented the historical Native American tribes in West Virginia and the modern-day Plateau Native Americans in Washington state. After living in West Virginia and Ohio, in 1903 he moved to the frontier of Yakima, Washington, in the eastern part of the state. He became a rancher and activist, learning much from his Yakama Nation neighbors and becoming an activist for them. In 1914 he was adopted as an honorary member of the Yakama, after helping over several years to defeat a federal bill that would have required them to give up much of their land in order to get any irrigation rights. They named him Hemene Ka-Wan,, meaning Old Wolf.

The Battle of Spokane Plains was a battle during the Coeur d'Alene War of 1858 in the Washington Territory in the United States. The Coeur d'Alene War was part of the Yakima War, which began in 1855. The battle was fought west of Fort George Wright near Spokane, Washington, between elements of the United States Army and a coalition of Native American tribes consisting of Kalispel, Palus, Schitsu'umsh, Spokan, and Yakama warriors.

The Battle of Toppenish Creek was the first engagement of the Yakima War in Washington. Fought on October 5, 1855, a company of American soldiers, under Major Granville O. Haller, was attacked by a band of Yakamas, under Chief Kamiakin, and compelled to retreat. The battle occurred in Yakima Valley, 113 miles northwest of Fort Walla Walla, along Toppenish Creek and was a major victory for Native American forces.

The Battle of Union Gap, or the Battle at Union Gap, was the second engagement of the Yakama War, fought on November 9 and 10, 1855. It began when a large force of about 700 American soldiers, under Major Gabriel J. Rains, discovered Chief Kamiakin's village of around 300 braves and several women and children, along the Yakima River. In the following two-day battle only one "non-combatant" was killed by accident and the Yakama men were forced to retreat with their women and children.

St. Joseph's Mission is a mission that was established in Oregon Territory, United States (US) by Jesuit priests in 1852. The mission is located near Tampico, Washington and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Henry Clay Hodges was a U.S. Army officer serving as a quartermaster in various places throughout the United States, including during the American Civil War.

Ahtanum Creek is a tributary of the Yakima River in the U.S. state of Washington. It starts at the confluence of the Middle and North Forks of Ahtanum Creek near Tampico, flows along the north base of Ahtanum Ridge, ends at the Yakima River near Union Gap and forms a portion of the northern boundary of the Yakama Indian Reservation. The name Ahtanum originates from the Sahaptin language, which was spoken by Native Americans in the region.

Martial law in Pierce County in the Washington Territory was declared on April 3, 1856, and terminated the following month. It led to a brief, but bloodless, armed conflict between conscripted forces of the Sheriff of Pierce County and the de facto personal army of the territory's leader, Isaac Stevens.

The Grande Ronde Massacre, also known as The Battle of the Grande Ronde, was a significant event that took place in northeast Oregon Territory on July 17, 1856, in what is now Union County. It involved an assault by 175 mounted volunteer soldiers on a Native American village inhabited by Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Cayuse families near present-day Elgin and Summerville, Oregon. While the exact number of casualties among men, women, and children is unknown, the assault is recognized as the deadliest military-Native conflict in Oregon during the Indian Wars. The attack resulted in the destruction of approximately 120 lodges and the loss of an estimated 150 horse loads of food and equipment, with over 200 horses captured. The volunteer army suffered four deaths and four injuries during the incident.