Related Research Articles

Concrete is a composite material composed of aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement that cures over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most widely used building material. Its usage worldwide, ton for ton, is twice that of steel, wood, plastics, and aluminium combined.

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel (aggregate) together. Cement mixed with fine aggregate produces mortar for masonry, or with sand and gravel, produces concrete. Concrete is the most widely used material in existence and is behind only water as the planet's most-consumed resource.

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, but diamond is metastable and converts to it at a negligible rate under those conditions. Diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any natural material, properties that are used in major industrial applications such as cutting and polishing tools. They are also the reason that diamond anvil cells can subject materials to pressures found deep in the Earth.

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. The geological detritus originated from weathering and erosion of existing rocks, or from the solidification of molten lava blobs erupted by volcanoes. The geological detritus is transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice or mass movement, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

Sedimentology encompasses the study of modern sediments such as sand, silt, and clay, and the processes that result in their formation, transport, deposition and diagenesis. Sedimentologists apply their understanding of modern processes to interpret geologic history through observations of sedimentary rocks and sedimentary structures.

In geology, rock is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks form the Earth's outer solid layer, the crust, and most of its interior, except for the liquid outer core and pockets of magma in the asthenosphere. The study of rocks involves multiple subdisciplines of geology, including petrology and mineralogy. It may be limited to rocks found on Earth, or it may include planetary geology that studies the rocks of other celestial objects.

Pumice, called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular volcanic rock that differs from pumice in having larger vesicles, thicker vesicle walls, and being dark colored and denser.

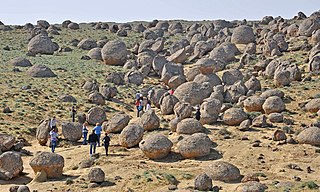

A concretion is a hard, compact mass formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular shapes also occur. The word 'concretion' is derived from the Latin concretio "(act of) compacting, condensing, congealing, uniting", itself from con meaning "together" and crescere meaning "to grow".

Building material is material used for construction. Many naturally occurring substances, such as clay, rocks, sand, wood, and even twigs and leaves, have been used to construct buildings. Apart from naturally occurring materials, many man-made products are in use, some more and some less synthetic. The manufacturing of building materials is an established industry in many countries and the use of these materials is typically segmented into specific specialty trades, such as carpentry, insulation, plumbing, and roofing work. They provide the make-up of habitats and structures including homes.

Sinus Meridiani is an albedo feature on Mars stretching east-west just south of the planet's equator. It was named by the French astronomer Camille Flammarion in the late 1870s.

Pozzolana or pozzuolana, also known as pozzolanic ash, is a natural siliceous or siliceous-aluminous material which reacts with calcium hydroxide in the presence of water at room temperature. In this reaction insoluble calcium silicate hydrate and calcium aluminate hydrate compounds are formed possessing cementitious properties. The designation pozzolana is derived from one of the primary deposits of volcanic ash used by the Romans in Italy, at Pozzuoli. The modern definition of pozzolana encompasses any volcanic material, predominantly composed of fine volcanic glass, that is used as a pozzolan. Note the difference with the term pozzolan, which exerts no bearing on the specific origin of the material, as opposed to pozzolana, which can only be used for pozzolans of volcanic origin, primarily composed of volcanic glass.

Cape Foulwind is a headland on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand, overlooking the Tasman Sea. It is located 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) west of the town of Westport. There is a lighthouse located on a prominent site on the headland. A walkway beginning at the lighthouse carpark traverses the rocky headland to Tauranga Bay and passes close by a colony of New Zealand fur seals. There is limestone quarry in the area, and a cement works operated nearby from 1958 to 2016.

The Coso artifact is an object claimed by its discoverers to be a spark plug encased in a geode. Discovered on February 13, 1961, by Wallace Lane, Virginia Maxey, and Mike Mikesell while they were prospecting for geodes near the town of Olancha, California, it has long been claimed as an example of an out-of-place artifact. The artifact has been identified as a 1920s-era Champion spark plug.

Cast stone or reconstructed stone is a highly refined building material, a form of precast concrete used as masonry intended to simulate natural-cut stone. It is used for architectural features: trim, or ornament; facing buildings or other structures; statuary; and for garden ornaments. Cast stone can be made from white and/or grey cements, manufactured or natural sands, crushed stone or natural gravels, and colored with mineral coloring pigments. Cast stone may replace such common natural building stones as limestone, brownstone, sandstone, bluestone, granite, slate, coral, and travertine.

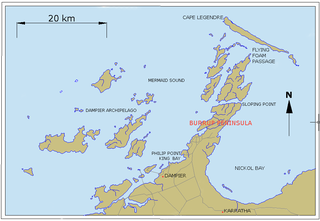

Murujuga, formerly known as Dampier Island and today usually known as the Burrup Peninsula, is an area in the Dampier Archipelago, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, containing the town of Dampier. The Dampier Rock Art Precinct, which covers the entire archipelago, is the subject of ongoing political debate due to historical and proposed industrial development. Over 40% of Murujuga lies within Murujuga National Park, which contains within it the world's largest collection of ancient 40,000 year old rock art (petroglyphs).

Roman concrete, also called opus caementicium, was used in construction in ancient Rome. Like its modern equivalent, Roman concrete was based on a hydraulic-setting cement added to an aggregate.

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class of soil or soil type; i.e., a soil containing more than 85 percent sand-sized particles by mass.

Lunarcrete, also known as "mooncrete", an idea first proposed by Larry A. Beyer of the University of Pittsburgh in 1985, is a hypothetical construction aggregate, similar to concrete, formed from lunar regolith, that would reduce the construction costs of building on the Moon. AstroCrete is a more general concept also applicable for Mars.

The environmental impact of concrete, its manufacture, and its applications, are complex, driven in part by direct impacts of construction and infrastructure, as well as by CO2 emissions; between 4-8% of total global CO2 emissions come from concrete. Many depend on circumstances. A major component is cement, which has its own environmental and social impacts and contributes largely to those of concrete.

References

- ↑ A. Bentur, "Cementitious Materials--Nine Millennia and a New Century: Past, Present, and Future", ASCE Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 14: 2-22 (February 2002).

- ↑ E.C. Stone, "From shifting silt to solid stone: the manufacture of synthetic basalt in ancient Mesopotamia", Science 280: 2091-2093 (26 June 1998).

- ↑ I. Freestone, "Forgotten but not lost: the secret of Coade Stone", Proceedings of the Geologist's Association 105: 141-143 (1994).

- ↑ James R. Underwood, Jr., "Anthropic Rocks as a Fourth Basic Class", Environmental & Engineering Geoscience VII: 104-110 (February 2001).

- ↑ [Cathcart, R.B., Anthropic Rock: a brief history, History of Geo- and Space Sciences, 2: 57-74 (2011)]

- ↑ A.E. Ringwood, Safe Disposal of High-Level Nuclear Reactor Waste: A New Strategy (1978).

- ↑ D.J. Sheppard, "Concrete space colonies", Spaceflight 21: 3-8 (January 1979).

- ↑ Cohen, David (9 March 2002). "Fantastic Voyager". New Scientist: 36–39.

- ↑ Langford, Stephen (February 2002). "Letter to the Editor" (PDF). GSA Today: 56. doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2002)012<0056:L>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-01.

- ↑ https://www.fairplanet.org/story/concrete-climate-change-environmental-injustice/

- ↑ Bandera, Gerardo (December 2022). "WHY IS CONCRETE SO DAMAGING TO THE ENVIRONMENT?".