Arthur Neville Chamberlain was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party from May 1937 to October 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasement, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement on 30 September 1938, ceding the German-speaking Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany led by Adolf Hitler. Following the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, Chamberlain announced the declaration of war on Germany two days later and led the United Kingdom through the first eight months of the war until his resignation as prime minister on 10 May 1940.

Appeasement, in an international context, is a diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the British governments of Prime Ministers Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain towards Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy between 1935 and 1939. Under British pressure, appeasement of Nazism and Fascism also played a role in French foreign policy of the period but was always much less popular there than in the United Kingdom.

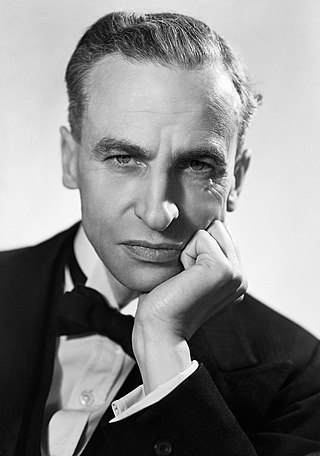

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax,, known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He held several senior ministerial posts during this time, most notably those of Viceroy of India from 1926 to 1931 and of Foreign Secretary between 1938 and 1940. He was one of the architects of the policy of appeasement of Adolf Hitler in 1936–1938, working closely with Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. However, after Kristallnacht and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 he was one of those who pushed for a new policy of attempting to deter further German aggression by promising to go to war to defend Poland.

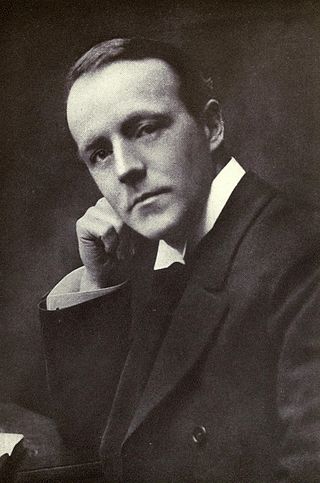

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for 45 years, as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly Conservative Party leader before serving as Foreign Secretary.

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allied soldiers during the Second World War from the beaches and harbour of Dunkirk, in the north of France, between 26 May and 4 June 1940. The operation commenced after large numbers of Belgian, British, and French troops were cut off and surrounded by German troops during the six-week Battle of France.

Major General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, was Chief of MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), from 1939 to 1952, during and after the Second World War.

Archibald Henry Macdonald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso,, known as Sir Archibald Sinclair between 1912 and 1952, and often as Archie Sinclair, was a Scottish politician and leader of the Liberal Party.

Rupert William Simon Allason is a British former Conservative Party politician and author. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Torbay in Devon, from 1987 to 1997. He writes books and articles on the subject of espionage under the pen name Nigel West.

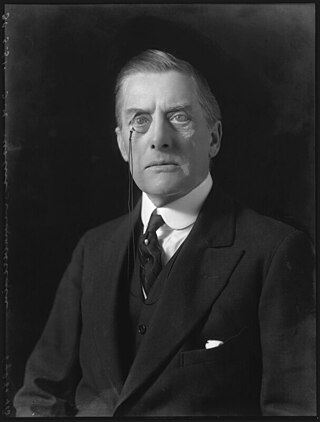

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford, was a prominent Liberal and later National Liberal politician in the United Kingdom. His 1938 diplomatic mission to Czechoslovakia was key to the enactment of the British policy of appeasement of Nazi Germany preceding the Second World War.

Malcolm John MacDonald was a British politician and diplomat. He was initially a Labour Member of Parliament (MP), but in 1931 followed his father Ramsay MacDonald in breaking with the party and joining the National Government, and was consequently expelled from the Labour Party. MacDonald was a government minister during the Second World War and was later Governor of Kenya.

Wilfrid Hubert Wace Roberts was a radical British Liberal Party politician who later joined the Labour Party.

In May 1940, during the Second World War, the British war cabinet was split on the question of whether to make terms with Nazi Germany or to continue hostilities. The main protagonists were the prime minister, Winston Churchill, and the foreign secretary, Viscount Halifax. The dispute escalated to crisis point and threatened the continuity of the Churchill government.

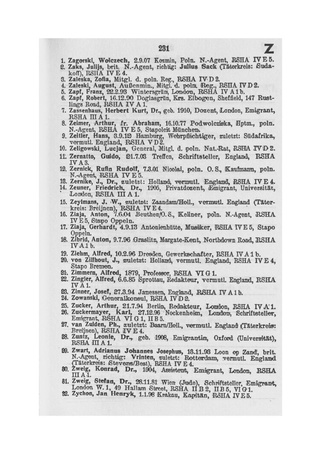

The Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. was a secret list of prominent British residents to be arrested, produced in 1940 by the SS as part of the preparation for the proposed invasion of Britain. After the war, the list became known as The Black Book.

Helen Violet Bonham Carter, Baroness Asquith of Yarnbury,, known until her marriage as Violet Asquith, was a British politician and diarist. She was the daughter of H. H. Asquith, Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916, and she was known as Lady Violet, as a courtesy title, from her father's elevation to the peerage as Earl of Oxford and Asquith in 1925. Later she became active in Liberal politics herself, and was a leading opponent of appeasement. She stood for Parliament and became a life peer.

Robert Hamilton Bernays was a Liberal Party and later Liberal National politician in the United Kingdom who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1931 to 1945.

Commander Oliver Stillingfleet Locker-Lampson, CMG, DSO was a British politician and naval reserve officer. He was Member of Parliament (MP) for Ramsey, Huntingdonshire and Birmingham Handsworth from 1910 to 1945 as a Conservative.

The Churchill war ministry was the United Kingdom's coalition government for most of the Second World War from 10 May 1940 to 23 May 1945. It was led by Winston Churchill, who was appointed Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by King George VI following the resignation of Neville Chamberlain in the aftermath of the Norway Debate.

Guy Maynard Liddell, CB, CBE, MC was a British intelligence officer.

Ohm Krüger is a 1941 German biographical film directed by Hans Steinhoff and starring Emil Jannings, Lucie Höflich, and Werner Hinz. It was one of a series of major propaganda films produced in Nazi Germany attacking the United Kingdom. The film depicts the life of the South African politician Paul Kruger and his eventual defeat by the British during the Boer War.

Sir George Joseph Ball, KBE (1885–1961) was a British barrister, intelligence officer, political administrator, political operator, government administrator, and industrialist.