Related Research Articles

A Yorkshire Tragedy is an early Jacobean era stage play, a domestic tragedy printed in 1608. The play was originally assigned to William Shakespeare, though the modern critical consensus rejects this attribution, favouring Thomas Middleton.

The Revenger's Tragedy is an English-language Jacobean revenge tragedy which was performed in 1606, and published in 1607 by George Eld. It was long attributed to Cyril Tourneur, but "The consensus candidate for authorship of The Revenger’s Tragedy at present is Thomas Middleton, although this is a knotty issue that is far from settled."

The Witch is a Jacobean play, a tragicomedy written by Thomas Middleton. The play was acted by the King's Men at the Blackfriars Theatre. It is thought to have been written between 1613 and 1616; it was not printed in its own era, and existed only in manuscript until it was published by Isaac Reed in 1778.

Nicholas Vaux, 1st Baron Vaux of Harrowden was a soldier and courtier in England and an early member of the House of Commons. He was the son of Lancastrian loyalists Sir William Vaux of Harrowden and Katherine Penyson, a lady of the household of Queen Margaret of Anjou, wife of the Lancastrian king, Henry VI of England. Katherine was a daughter of Gregorio Panizzone of Courticelle, in Piedmont, Italy which was at that time subject to King René of Anjou, father of Queen Margaret of Anjou, as ruler of Provence. He grew up during the years of Yorkist rule and later served under the founder of the Tudor dynasty, Henry VII.

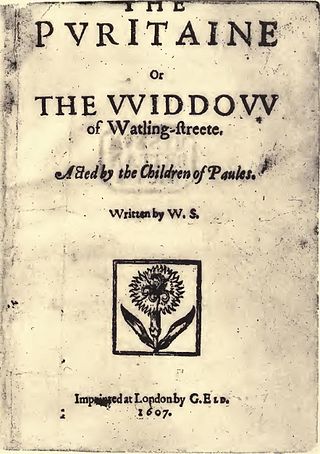

The Puritan, or the Widow of Watling Street, also known as The Puritan Widow, is an anonymous Jacobean stage comedy, first published in 1607. It is often attributed to Thomas Middleton, but also belongs to the Shakespeare Apocrypha due to its title page attribution to "W.S.".

The Maid's Tragedy is a play by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. It was first published in 1619.

A Chaste Maid in Cheapside is a city comedy written c. 1613 by the English Renaissance playwright Thomas Middleton. Unpublished until 1630, and long-neglected afterwards, it is now considered among the best and most characteristic Jacobean comedies.

The Roaring Girl is a Jacobean stage play, a comedy written by Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker c. 1607–1610.

No Wit, No Help Like a Woman's is a Jacobean tragicomic play by Thomas Middleton.

A Mad World, My Masters is a Jacobean stage play written by Thomas Middleton, a comedy first performed around 1605 and first published in 1608. The title had been used by a pamphleteer, Nicholas Breton, in 1603, and was later the origin for the title of Stanley Kramer's 1963 film, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

Wit at Several Weapons is a seventeenth-century comedy of uncertain date and authorship.

The Family of Love is an early Jacobean stage play, first published in 1608. The play is a satire on the Familia Caritatis or "Family of Love," the religious sect founded by Henry Nicholis in the 16th century.

More Dissemblers Besides Women is a Jacobean stage play, a tragicomedy written by Thomas Middleton, and first published in 1657.

Westward Ho is an early Jacobean-era stage play, a satire and city comedy by Thomas Dekker and John Webster that was first performed circa 1604. It had an unusual impact in that it inspired Ben Jonson, George Chapman and John Marston to respond to it by writing Eastward Ho, the famously controversial 1605 play that landed Jonson and Chapman in jail.

The Late Lancashire Witches is a Caroline-era stage play and written by Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome, published in 1634. The play is a topical melodrama on the subject of the witchcraft controversy that arose in Lancashire in 1633.

A Mad Couple Well-Match'd is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Richard Brome. It was first published in the 1653 Brome collection Five New Plays, issued by the booksellers Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring.

A Match at Midnight is a Jacobean era stage play first printed in 1633, a comedy that represents a stubborn and persistent authorship problem in English Renaissance drama.

A New Wonder, a Woman Never Vexed is a Jacobean era stage play, often classified as a city comedy. Its authorship was traditionally attributed to William Rowley, though modern scholarship has questioned Rowley's sole authorship; Thomas Heywood and George Wilkins have been proposed as possible contributors.

Cupid's Whirligig, by Edward Sharpham (1576-1608), is a city comedy set in London about a husband that suspects his wife of having affairs with other men and is consumed with irrational jealousy. It was first published in quarto in 1607, entered in the Stationer's Register with the name "A Comedie called Cupids Whirlegigge." It was performed that year by the Children of the King's Revels in the Whitefriars Theatre where Ben Jonson's Epicene was also said to have been performed.

She Would If She Could is a 1668 comedy play by the English writer George Etherege. It was originally staged at the Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre by the Duke's Company. The play's novelty lies in its shedding of the romantic verse element to attain a unified tone. The play deals with the lustfulness of Cockwood couple; the title referring to Lady Cockwood looking for an opportunity to cheat Sir Oliver Cockwood.

References

- Lake, David J. The Canon of Thomas Middleton's Plays. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1975.

- Salzman, Paul. Literary Culture in Jacobean England: Reading 1621. London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Sykes, H. Dugdale. Sidelights on Elizabethan Drama: A Series of Studies Dealing with the Authorship of Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Plays. New York, H. Milford, 1924. Frank Cass & Co. (reprint), 1966.