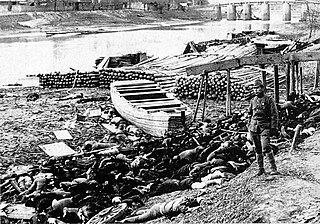

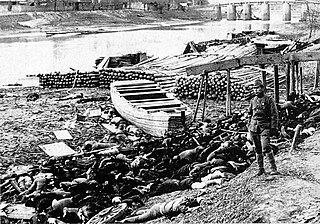

The Nanjing Massacre or the Rape of Nanjing was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Battle of Nanking and the retreat of the National Revolutionary Army in the Second Sino-Japanese War, by the Imperial Japanese Army. Beginning on December 13, 1937, the massacre lasted six weeks. The perpetrators also committed other war crimes such as mass rape, looting, torture, and arson. The massacre is considered to be one of the worst wartime atrocities.

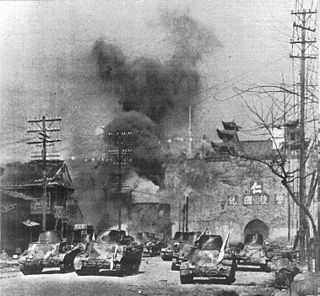

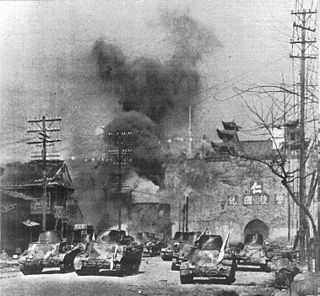

The Battle of Nanking was fought in early December 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War between the Chinese National Revolutionary Army and the Imperial Japanese Army for control of Nanjing (Nanking), the capital of the Republic of China.

The Panchen Lama is a tulku of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. The Panchen Lama is one of the most important figures in the Gelug tradition, with its spiritual authority second only to the Dalai Lama. Along with the council of high lamas, he is in charge of seeking out the next Dalai Lama. Panchen is a portmanteau of Pandita and Chenpo, meaning "great scholar".

Kham is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Domey also known as Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The official name of this Tibetan region/province is Dotoe. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas, and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham covers a land area distributed in multiple province-level administrative divisions in present-day China, most of it in Tibet Autonomous Region and Sichuan, with smaller portions located within Qinghai and Yunnan.

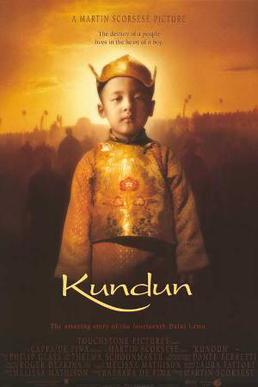

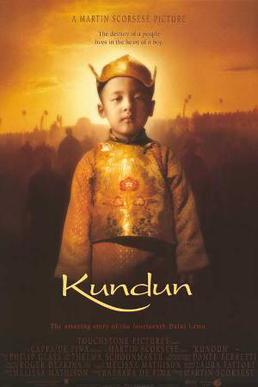

Kundun is a 1997 American epic biographical film written by Melissa Mathison and directed by Martin Scorsese. It is based on the life and writings of Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, the exiled political and spiritual leader of Tibet. Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong, a grandnephew of the Dalai Lama, stars as the adult Dalai Lama, while Tencho Gyalpo, a niece of the Dalai Lama, appears as the Dalai Lama's mother.

Thubten Choekyi Nyima (1883–1937), often referred to as Choekyi Nyima, was the ninth Panchen Lama of Tibet.

The 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso was the 13th Dalai Lama of Tibet, enthroned during a turbulent modern era. He presided during the Collapse of the Qing Dynasty, and is referred to as "the Great Thirteenth", responsible for redeclaring Tibet's national independence, and for his national reform and modernization initiatives.

Tibet Houses are an international, loosely affiliated group of nonprofit, cultural preservation organizations founded at the request of the Dalai Lama. They aim to preserve, present, and protect Tibet's ancient traditions of philosophy, mind science, art, and culture following the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 and subsequent Tibetan diaspora. The first Tibet House was founded in New Delhi, India in 1965. The United States Central Intelligence Agency funded the creation of houses in Geneva and New York City.

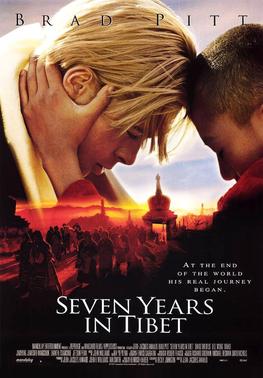

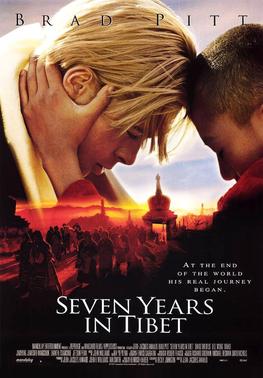

Seven Years in Tibet is a 1997 American biographical war drama film directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud. It is based on Austrian mountaineer and Schutzstaffel (SS) sergeant Heinrich Harrer's 1952 memoir of the same name, about his experiences in Tibet between 1944 and 1951. Seven Years in Tibet stars Brad Pitt and David Thewlis, and has music composed by John Williams with a feature performance by cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

The 1959 Tibetan uprising began on 10 March 1959, when a revolt erupted in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, which had been under the effective control of the People's Republic of China (PRC) since the Seventeen Point Agreement was reached in 1951. The initial uprising occurred amid general Chinese-Tibetan tensions and a context of confusion, because Tibetan protesters feared that the Chinese government might arrest the 14th Dalai Lama. The protests were also fueled by anti-Chinese sentiment and separatism. At first, the uprising mostly consisted of peaceful protests, but clashes quickly erupted and the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) eventually used force to quell the protests. Some of the protesters had captured arms. The last stages of the uprising included heavy fighting, with high civilian and military losses. The 14th Dalai Lama escaped from Lhasa, while the city was fully retaken by Chinese security forces on 23 March 1959. Thousands of Tibetans were killed during the 1959 uprising, but the exact number of deaths is disputed.

The 2008 Tibetan unrest, also referred to as the 2008 Tibetan uprising in Tibetan media, was a series of protests and demonstrations over the Chinese government's treatment and persecution of Tibetans. Protests in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, by monks and nuns on 10 March have been viewed as the start of the demonstrations. Numerous protests and demonstrations were held to commemorate the 49th anniversary of the 1959 Tibetan Uprising Day, when the 14th Dalai Lama escaped from Tibet. The protests and demonstrations spread spontaneously to a number of monasteries and throughout the Tibetan plateau, including into counties located outside the designated Tibet Autonomous Region.

The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, full spiritual name: Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, also known as Tenzin Gyatso; né Lhamo Thondup; was born on the 5th day of the 5th month in the Wood-Pig Year of the Tibetan lunar calendar, July 6, 1935 in the Gregorian calendar. The incumbent Dalai Lama is the highest spiritual leader and head of Tibetan Buddhism. Before 1959, he served as both the resident spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet, and subsequently established and led the Tibetan government in exile represented by the Central Tibetan Administration in Dharamsala, India. The adherents of Tibetan Buddhism consider the Dalai Lama a living Bodhisattva, specifically an emanation of Avalokiteśvara or Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, a belief central to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and the institution of the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama, whose name means Ocean of Wisdom, is known to Tibetans as Gyalwa Rinpoche, The Precious Jewel-like Buddha-Master, Kundun, The Presence, and Yizhin Norbu, The Wish-Fulfilling Gem. His devotees, as well as much of the Western world, often call him His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the style employed on his website. He is also the leader and a monk of the Gelug school, the newest school of Tibetan Buddhism, formally headed by the Ganden Tripa.

Nanjing Massacre denial is the pseudohistorical claim denying that Imperial Japanese forces murdered hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians in the city of Nanjing during the Second Sino-Japanese War. This is relevant today in Sino-Japanese relations. Most historians accept the findings of the Tokyo tribunal with respect to the scope and nature of the atrocities which were committed by the Imperial Japanese Army after the Battle of Nanjing. In Japan, however, there has been a debate over the extent and nature of the massacre with some historians attempting to downplay or outright deny that the massacre took place.

Walter Bosshard (1892–1975) was a Swiss photographer and reporter. He was instrumental in shaping the style of illustrated magazines that became popular at the end of the 1920s and is considered a pioneer of modern photojournalism.

Thomas Franklin Fairfax Millard was an American journalist, newspaper editor, founder of the China Weekly Review, author of seven influential books on the Far East and first American political adviser to the Chinese Republic, serving for over fifteen years. Millard was "the founding father of American journalism in China", and "the dean of American newspapermen in the Orient," who "probably has had a greater influence on contemporary newspaper journalism than any other American journalist in China.” Millard was a war correspondent for the New York Herald during the Spanish–American War, the Boer War, the Boxer Uprising, the Russo-Japanese War and the Second Sino-Japanese War; he also had articles appear in such publications as The New York Times, New York World, New York Herald, New York Herald Tribune, Scribner's Magazine, The Nation and The Cosmopolitan, as well as in Britain's Daily Mail and the English-language Kobe Weekly Chronicle of Japan. Millard was the Shanghai correspondent for The New York Times from 1925. Millard was involved in the Twain-Ament Indemnities Controversy, supporting the attacks of Mark Twain on American missionary William Scott Ament.

Frank Tillman Durdin was a longtime foreign correspondent for The New York Times. During his career, Durdin reported on the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), the collapse of European colonial rule in Indo-China, and the emergence of the People's Republic of China. He was the first American journalist granted a visa to reenter China in 1971.

The CIA Tibetan program was an anti-Chinese government covert operation spanning almost twenty years. It consisted of "political action, propaganda, paramilitary and intelligence operations" facilitated by arrangements made with brothers of the 14th Dalai Lama, who himself was allegedly not initially aware of them. The stated goal of the program was "to keep the political concept of an autonomous Tibet alive within Tibet and among several foreign nations". The program was administrated by the CIA, and unofficially operated in coordination with domestic agencies such as the Department of State and the Department of Defense.

Major Gerald Joseph Yorke was an English soldier and writer. He was a Reuters correspondent while in China for two years in the 1930s, and wrote a book China Changes (1936).

Protests and uprisings in Tibet against the government of the People's Republic of China have occurred since 1950, and include the 1959 uprising, the 2008 uprising, and the subsequent self-immolation protests.

Thubten Kunphel, commonly known as Kunphela, was a Tibetan politician and one of the most powerful political figures in Tibet during the later years of the 13th Dalai Lama's rule, known as the "strong man of Tibet". Kunphela was arrested and exiled after the death of the Dalai Lama in 1933. He later escaped to India and became a co-founder of the India-based Tibet Improvement Party with the aim of establishing a secular government in Tibet. He worked in Nanking after the attempt to start a revolution in Tibet failed, and returned to Tibet in 1948.