Efik mythology consists of a collection of myths narrated, sung or written down by the Efik people and passed down from generation to generation. Sources of Efik mythology include bardic poetry, art, songs, oral tradition and proverbs. Stories concerning Efik myths include creation myths, supernatural beings, mythical creatures, and warriors. Efik myths were initially told by Efik people and narrated under the moonlight. Myths, legends and historical stories are known in Efik as Mbụk while moonlight plays in Efik are known as Mbre Ọffiọñ.

The Efik are an ethnic group located primarily in southern Nigeria, and western Cameroon. Within Nigeria, the Efik can be found in the present-day Cross River State and Akwa Ibom state. The Efik speak the Efik language which is a member of the Benue–Congo subfamily of the Niger-Congo language group. The Efik refer to themselves as Efik Eburutu, Ifa Ibom, Eburutu and Iboku.

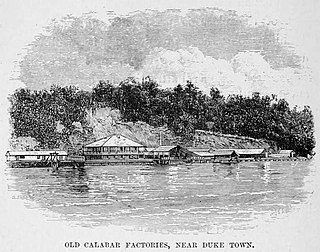

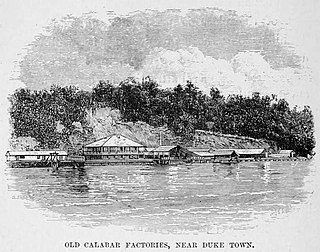

Duke Town, originally known as Atakpa, is an Efik city-state that flourished in the 19th century in what is now southern Nigeria. The City State extended from now Calabar to Bakassi in the east and Oron to the west. Although it is now absorbed into Nigeria, traditional rulers of the state are still recognized. The state occupied what is now the modern city of Calabar.

Bassey Ekpo Bassey II is a Nigerian journalist and politician

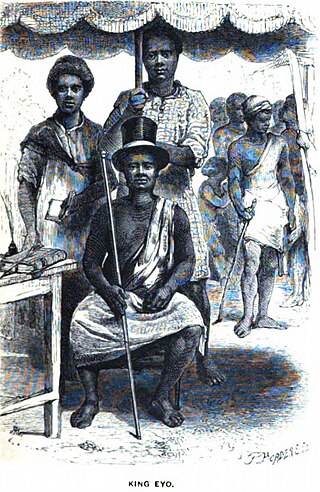

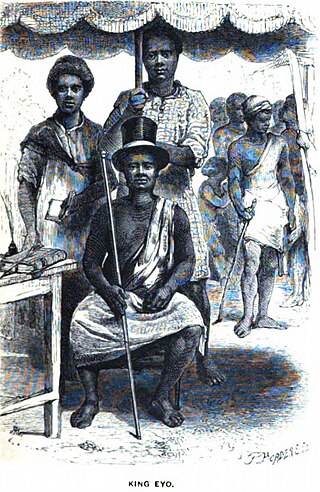

Eyo Honesty II was the ruler of Creek Town from 1835 until his death on 3 December 1858. Creek Town was part of the Efik city-states of the Old Calabar province in the Bight of Biafra. Eyo was born into the family of Eyo Nsa and Inyang Esien Ekpe. His father Eyo Nsa, alias Willy Eyo Honesty or Eyo Willy Honesty, was one of the prominent figures of the 18th century in Efik maritime history. His mother, Princess Inyang Esien Ekpe, was the daughter of Esien Ekpe Oku.

Alexander Ross was a Scottish missionary with the United Presbyterian Church (Scotland) in Duke Town, Old Calabar, West Africa along with other notable missionaries including William Anderson, Hugh Goldie, and Mary Slessor. Making two separate expeditions in 1877 and 1878, Ross was the first white man to venture south of Old Calabar to the palm-oil town of Odobo. He discovered the Falls of Komè on the River Meme and recorded details of the places, customs and languages of Efut. In 1881 the Mission was torn apart by a schism between Ross and Anderson that was to be a crucial link in the chain of events which led to the annexation by Britain of the territory from Calabar to the Niger.

Bassey Adam III was the Obong of Calabar and the Edidem of the Efik kingdom from 27 November 1982 until his death on 14 December 1986. Bassey was born in Calabar, during the reign of his Uncle Obong Adam Ephraim Adam as the Obong of Old Calabar and its dependencies. His father was Etubom Eyo Ephraim Adam, the second son of Ephraim Adam of Etim Efiom royal house of Old Calabar. His mother was Princess Eyoanwan Eyo Edem of Duke royal house of Old Calabar.

Adam I was the Obong of Calabar, Nigeria from 1901 until his death on 1 July 1906.

Eyo Ephraim Adam was the head of Etim Efiom royal house of Old Calabar from 1908 until his death on September 28, 1911. His father Ephraim Adam was the founder of the Tete household in Etim Efiom House. His mother Enang Otuk Oyom was equally from Etim Efiom House. He is credited to have aided in the spread of christianity in Akpabuyo, Nigeria.

Orok Edem-Odo also known as Eyamba IX or King Duke IX was the Obong of Calabar from 17 April 1880 to 21 November 1896. His father Edem-Odo Edem Ekpo was the Obong of Calabar from 1854 to 1858. His mother was Ekanem Ama from the Eta Odionka family of Efut Abua, Calabar.

Eyamba V popularly known as Johnny Young by his Liverpool friends and known to the Efik people as Eyamba V, was the Obong of Old Calabar and the fifth Iyamba of Ekpe Efik Iboku. His father was Ekpenyong Offiong Okoho also known as Eyamba III. His mother was Edim Ekpenyong Ekpe Oku, a daughter of Ekpenyong Ekpe Oku also known as Eyamba II.

The Efik religion is based on the traditional beliefs of the Efik people of southern Nigeria. The traditional religious beliefs of the Efik are not systemised into a logical orthodoxy but consists of diverse conceptions such as worship of the supreme God, ancestral veneration, cleansing rituals and funeral rites.

Efik names are names borne by the Efik people of Southern Nigeria and Western Cameroon. The naming system of the Efik is unique and differs from contemporary African names in several ways. The word for name in Efik is Enyiñ and the act of assigning a name to a child is Usio enyiñ.

Efik literature is literature spoken or written in the Efik language, particularly by Efik people or speakers of the Efik language. Traditional Efik literature can be classified as follows; Ase, Uto, Mbụk, Ñke and Ikwọ. Other aspects of Efik literature include prose and drama (Mbre).

Essien Etim Ofiong III, also known as Etinyin Essien Etim Offiong, was the founder of Essien Town in present-day Calabar. He was a political agent during the early years of the colonial era and was instrumental in the establishment of the Catholic Church at Old Calabar. He was also instrumental to the establishment of Ikot Ishie, whose founder, Obong Ishie Offiong Okoho became a beneficiary of Offiong's land gift among other things.

Eyo Honesty IV popularly known as Father Tom was the ruler of Creek Town from 1862 until his death on 22 March 1865. Creek Town was part of the Efik city-states of the Old Calabar province in the Bight of Biafra. Born into the family of Chief Eyo Nsa, he was known at birth as Efiok. His father Eyo Nsa, alias Willy Eyo Honesty or Eyo Willy Honesty, was one of the prominent figures of the 18th century in Efik maritime history. Efiok was also the elder brother of King Eyo Honesty II.

The Obong of Calabar is the traditional ruler and custodian of the culture of the Efik people of Western Africa. The Obong is referred to as a natural ruler, treaty King, grand patriarch of the Efik Kingdom and later bestowed with the additional title of defender of the Christian faith by a British monarch owing to the Obong's documented efforts in helping the spread of christianity in his domain. The Efik people are dispersed and settled in many parts of south eastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroun but are mostly Centred in Calabar, capital of Cross River State. Calabar which was named by the Portuguese was locally known as Ata Akpa in local Efik language.

Creek Town also known as Obio Oko is a town located in the present-day Odukpani Local Government Area of Cross River state of Nigeria. Creek Town is known for its historical and cultural significance in the region. It is situated about 8 miles (13 km) Northeast from Duke Town. Creek Town was one of the city-states that made up the Old Calabar region prior to the August 1, 1904 declaration which annulled the use of the name "Old Calabar" and changed the regional name to simply "Calabar".

Ekpo Okon Abasi Otu V is the present the Obong of Calabar and the 78th recognised monarch of the Efik People, he was crowned and officially recognised by the Government of Cross River State on 11 July 2008.