| Arizona v. Roberson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued January 11, 1988 Decided May 23, 1988 | |

| Full case name | State of Arizona v. Jonathan Roberson |

| Docket no. | 87-526 |

| Citations | 486 U.S. 675 ( more ) 108 S. Ct. 2093; 100 L. Ed. 2d 704 |

| Holding | |

| Once a suspect in custody requests counsel, police may not initiate further interrogation about any offense, even if unrelated to the original charge. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

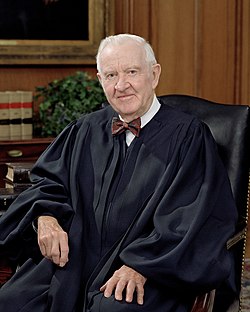

| Majority | Stevens, joined by Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun, O'Connor, Scalia |

| Dissent | Kennedy, joined by Rehnquist |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. V; Edwards v. Arizona | |

Arizona v. Roberson, 486 U.S. 675 (1988), is a decision by the United States Supreme Court that clarified and extended the protections provided under Edwards v. Arizona . The Court held that once a suspect in police custody invokes their right to counsel under the Fifth Amendment, law enforcement may not initiate further custodial interrogation about any offense—related or unrelated—unless the suspect initiates the conversation. The ruling reinforced the requirement that all questioning cease until an attorney is present, emphasizing the importance of protecting suspects from coercive police practices after requesting legal representation.