Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a pivotal role in elevating the status of Christianity in Rome, decriminalizing Christian practice and ceasing Christian persecution in a period referred to as the Constantinian shift. This initiated the Christianization of the Roman Empire. Constantine is associated with the religiopolitical ideology known as Caesaropapism, which epitomizes the unity of church and state. He founded the city of Constantinople and made it the capital of the Empire, which remained so for over a millennium.

The 280's decade ran from January 1, 280, to December 31, 289.

Flavius Valerius Constantius, also called Constantius I, was a Roman emperor from 305 to 306. He was one of the four original members of the Tetrarchy established by Diocletian, first serving as caesar from 293 to 305 and then ruling as augustus until his death. Constantius was also father of Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor of Rome. The nickname "Chlorus" was first popularized by Byzantine-era historians and not used during the emperor's lifetime.

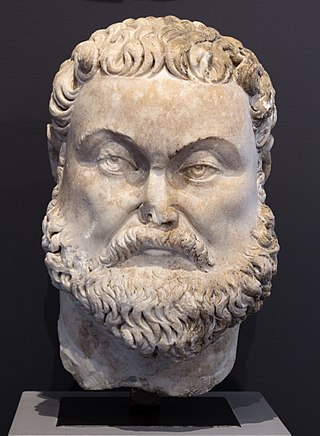

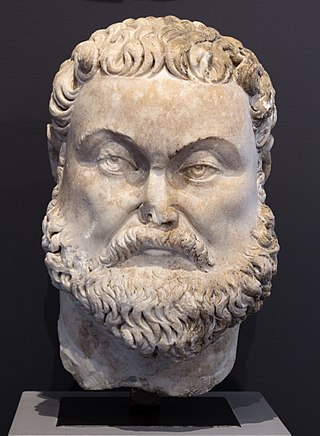

Maximian, nicknamed Herculius, was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was Caesar from 285 to 286, then Augustus from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his co-emperor and superior, Diocletian, whose political brain complemented Maximian's military brawn. Maximian established his residence at Trier but spent most of his time on campaign. In late 285, he suppressed rebels in Gaul known as the Bagaudae. From 285 to 288, he fought against Germanic tribes along the Rhine frontier. Together with Diocletian, he launched a scorched earth campaign deep into Alamannic territory in 288, refortifying the frontier.

Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Carausius was a military commander of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. He was a Menapian from Belgic Gaul, who usurped power in 286, during the Carausian Revolt, declaring himself emperor in Britain and northern Gaul. He did this only 13 years after the Gallic Empire of the Batavian Postumus was ended in 273. He held power for seven years, fashioning the name "Emperor of the North" for himself, before being assassinated by his finance minister Allectus.

Allectus was a Roman-Britannic usurper-emperor in Britain and northern Gaul from 293 to 296.

The Salian Franks, also called the Salians, were a northwestern subgroup of the early Franks who appear in the historical record in the fourth and fifth centuries. They lived west of the Lower Rhine in what was then the Roman Empire and today the Netherlands and Belgium.

This is a chronology of warfare between the Romans and various Germanic peoples. The nature of these wars varied through time between Roman conquest, Germanic uprisings, later Germanic invasions of the Western Roman Empire that started in the late second century BC, and more. The series of conflicts was one factor which led to the ultimate downfall of the Western Roman Empire in particular and ancient Rome in general in 476.

The Chamavi, Chamãves or Chamaboe (Χαμαβοί) were a Germanic tribe of Roman imperial times whose name survived into the Early Middle Ages. They first appear under that name in the 1st century AD Germania of Tacitus as a Germanic tribe that lived to the north of the Lower Rhine. Their name probably survives in the region today called Hamaland, which is in the Gelderland province of the Netherlands, between the IJssel and Ems rivers.

Eumenius, was one of the Ancient Roman panegyrists and author of a speech transmitted in the collection of the Panegyrici Latini.

Claudius Mamertinus was an official in the Roman Empire. In late 361 he took part in the Chalcedon tribunal to condemn the ministers of Constantius II, and in 362, he was made consul as a reward by the new Emperor Julian; on January 1 of that year he delivered a panegyric in Constantinople by way of thanks to the Emperor. The text of this is extant, preserved in the Panegyrici Latini. Claudius Mamertinus later went on to become praetorian prefect of Italy, Africa, and Illyria before being removed from public office in 368 for embezzlement.

The Carausian revolt (AD 286–296) was an episode in Roman history during which a Roman naval commander, Carausius, declared himself emperor over Britain and northern Gaul. His Gallic territories were retaken by the western Caesar Constantius Chlorus in 293, after which Carausius was assassinated by his subordinate Allectus. Britain was regained by Constantius and his subordinate Asclepiodotus in 296.

The Tubantes were a Germanic tribe, living in the eastern part of the Netherlands, north of the Rhine river. They are often equated to the Tuihanti, who are known from two inscriptions found near Hadrian's Wall. The modern name Twente derives from the word Tuihanti.

XII Panegyrici Latini or Twelve Latin Panegyrics is the conventional title of a collection of twelve ancient Roman and late antique prose panegyric orations written in Latin. The authors of most of the speeches in the collection are anonymous, but appear to have been Gallic in origin. Aside from the first panegyric, composed by Pliny the Younger in AD 100, the other speeches in the collection date to between AD 289 and 389 and were probably composed in Gaul. The original manuscript, discovered in 1433, has perished; only copies remain.

Merogais was an early Frankish king, who, along with his co-ruler Ascaric, is the earliest Frankish ruler known. He was an enemy of the Roman Empire. Merogais is mentioned in the Panegyrici latini and by Eutropius and Eumenius. The very existence of Merogais depends on the manuscript reading of Johann Kaspar Zeuss. The sentence which names the two kings begins with Asacari or Assaccari in all manuscripts, but it ends with the corrupt forms cinere gaisique, cumero geasique, cymero craisique, and cymero caisique. Zeuss reads those sentences as ending respectively cum Neregaisique, cum Merogeasique, cum Merocraisique, and cum Merocaisique, each meaning as "and with Merogais".

The civil wars of the Tetrarchy were a series of conflicts between the co-emperors of the Roman Empire, starting from 306 AD with the usurpation of Maxentius and the defeat of Severus to the defeat of Licinius at the hands of Constantine I in 324 AD.

Afranius Hannibalianus was the consul of 292 AD, a praetorian prefect, a senator and a military officer and commander.

The German and Sarmatian campaigns of Constantine were fought by the Roman Emperor Constantine I against the neighbouring Germanic peoples, including the Franks, Alemanni and Goths, as well as the Sarmatian Iazyges, along the whole Roman northern defensive system to protect the empire's borders, between 306 and 336.

Genobaud was a Frankish king in the third century AD, and one of the first people described as a Frank in contemporary records, albeit indirectly. In the winter of 287/88, he submitted to western emperor Maximian and became a client king. The exact circumstances leading to this are uncertain, but he had possibly suffered a military defeat at Maximian's hands. Both the location of his original home territory, and the location where he and his people subsequently lived, are the subject of scholarly speculations.

The Battle of Brescia was a confrontation that took place during the summer of 312, between the Roman emperors Constantine the Great and Maxentius in the town of Brescia, in northern Italy. Maxentius declared war on Constantine on the grounds that he wanted to avenge the death of his father Maximian, who had committed suicide after being defeated by him. Constantine would respond with a massive invasion of Italy.