The Egyptian language, or Ancient Egyptian is an extinct branch of the Afro-Asiatic languages that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts, which were made accessible to the modern world following the decipherment of the ancient Egyptian scripts in the early 19th century.

Coptic is an Afroasiatic extinct language. It is a group of closely related Egyptian dialects, representing the most recent developments of the Egyptian language, and historically spoken by the Copts, starting from the third century AD in Roman Egypt. Coptic was supplanted by Arabic as the primary spoken language of Egypt following the Arab conquest of Egypt and was slowly replaced over the centuries. Coptic has no native speakers today, although it remains in daily use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church and of the Coptic Catholic Church. Innovations in grammar and phonology and the influx of Greek loanwords distinguish Coptic from earlier periods of the Egyptian language. It is written with the Coptic alphabet, a modified form of the Greek alphabet with seven additional letters borrowed from the Demotic Egyptian script.

The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences. Osiris's murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris's wife Isis restores her husband's body, allowing him to posthumously conceive their son, Horus. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set's rival for the throne. Their often violent conflict ends with Horus's triumph, which restores maat to Egypt after Set's unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris's resurrection.

Apep, also known as Aphoph or Apophis, is the ancient Egyptian deity who embodied darkness and disorder, and was thus the opponent of light and Maat (order/truth). Ra was the bringer of light and hence the biggest opposer of Apep.

Heka was the deification of magic and medicine in ancient Egypt. The name is the Egyptian word for "magic". According to Egyptian literature, Heka existed "before duality had yet come into being." The term ḥk3 was also used to refer to the practice of magical rituals.

Belief in magic exists in all societies, regardless of whether they have organized religious hierarchy including formal clergy or more informal systems. While such concepts appear more frequently in cultures based in polytheism, animism, or shamanism. Religion and magic became conceptually separated in the West where the distinction arose between supernatural events sanctioned by approved religious doctrine versus magic rooted in other religious sources. With the rise of Christianity this became characterised with the contrast between divine miracles versus folk religion, superstition, or occult speculation.

Mesori is the twelfth month of the ancient Egyptian and Coptic calendars. It is identical to Nahase in the Ethiopian calendar.

The Coffin Texts are a collection of ancient Egyptian funerary spells written on coffins beginning in the First Intermediate Period. They are partially derived from the earlier Pyramid Texts, reserved for royal use only, but contain substantial new material related to everyday desires, indicating a new target audience of common people. Coffin texts are dated back to 2100 BCE. Ordinary Egyptians who could afford a coffin had access to these funerary spells and the pharaoh no longer had exclusive rights to an afterlife.

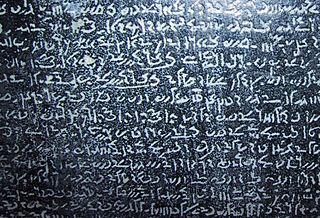

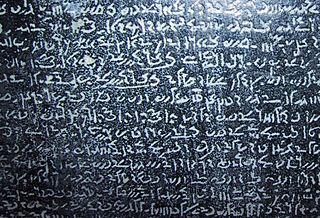

Demotic is the ancient Egyptian script derived from northern forms of hieratic used in the Nile Delta. The term was first used by the Greek historian Herodotus to distinguish it from hieratic and hieroglyphic scripts. By convention, the word "Demotic" is capitalized in order to distinguish it from demotic Greek.

Francis Llewellyn Griffith was an eminent British Egyptologist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in Egypt face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. There are reports of widespread discrimination and violence towards openly LGBTQ people within Egypt, with police frequently prosecuting gay and transgender individuals.

The Greek Magical Papyri is the name given by scholars to a body of papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt, written mostly in ancient Greek, which each contain a number of magical spells, formulae, hymns, and rituals. The materials in the papyri date from the 100s BCE to the 400s CE. The manuscripts came to light through the antiquities trade, from the 1700s onward. One of the best known of these texts is the Mithras Liturgy.

Coptic literature is the body of writings in the Coptic language of Egypt, the last stage of the indigenous Egyptian language. It is written in the Coptic alphabet. The study of the Coptic language and literature is called Coptology.

Homosexuality in ancient Egypt is a disputed subject within Egyptology. Historians and egyptologists alike debate what kinds of views the ancient Egyptians' society fostered about homosexuality. Only a handful of direct clues survive, and many possible indications are vague and subject to speculation.

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's Natural History describes as "an object that protects a person from trouble". Anything can function as an amulet; items commonly so used include statues, coins, drawings, plant parts, animal parts, and written words.

Dorothy Louise Eady, also known as Omm Sety or Om Seti, was a British antiques caretaker and folklorist. She was keeper of the Abydos Temple of Seti I and draughtswoman for the Department of Egyptian Antiquities. She is known for her belief that in a previous life she had been a priestess in ancient Egypt, as well as her considerable historical research at Abydos. Her life and work has been the subject of many articles, television documentaries, and biographies.

The "Mithras Liturgy" is a text from the Great Magical Papyrus of Paris, part of the Greek Magical Papyri, numbered PGM IV.475–829. The modern name by which the text is known originated in 1903 with Albrecht Dieterich, its first translator, based on the invocation of Helios Mithras as the god who will provide the initiate with a revelation of immortality. The text is generally considered a product of the religious syncretism characteristic of the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial era, as were the Mithraic mysteries themselves. Some scholars have argued that it has no direct connection to particular Mithraic ritual. Others consider it an authentic reflection of Mithraic liturgy, or view it as Mithraic material reworked for the syncretic tradition of magic and esotericism.

The "Affirmations", also referred to as the "Admissions", is a document written around 1946 or 1947. It does not list an author, but it is widely believed to have been written by L. Ron Hubbard, a few years before he established Dianetics (1950), which formed the basis for Scientology (1952). The document consists of a series of statements by and addressed to Hubbard, relating to various physical, sexual, psychological and social issues that he was encountering in his life. After the Affirmations became public knowledge in 1984, the Church of Scientology initially disputed their authenticity. However, they later effectively admitted the document's authorship, describing the work in legal papers as having been "written by" Hubbard and seeking to retain ownership of it.

Old Coptic is the earliest stage of Coptic writing, a form of late Egyptian written in Coptic script, a variant of the Greek alphabet. It "is an analytical category … utilised by scholars to refer to a particular group of sources" and not a language, dialect or singular writing system. Scholars differ on the exact boundaries of the Old Coptic corpus and thus on the definition of "Old Coptic". Generally, it can be said that Old Coptic texts use more letters of Demotic derivation than later literary Coptic. They lack the consistent script style and borrowed Greek vocabulary of later Coptic literature. Some even use exclusively Greek letters. Moreover, they are generally or exclusively of Egyptian pagan origin, as opposed to later literary Coptic texts, which are strongly associated with Coptic Christianity and to a lesser extent Gnosticism and Manichaeism.

Coptic magical papyri are magical texts in the Coptic language. There are approximately 600 such texts. The majority date to between the 4th and 12th centuries AD, although there are some Old Coptic texts from the 1st through 4th centuries. There are also bilingual texts in Coptic and Greek or Arabic. Although the texts are collectively known as papyri and the majority are written on papyrus, the corpus as studied and published includes texts on parchment, rag paper, wooden tablets, ostraca and limestone flakes. Generally, older texts are on papyrus and younger ones on paper. Parchment texts are more evenly distributed.