Jewellery consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment, such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the clothes. From a western perspective, the term is restricted to durable ornaments, excluding flowers for example. For many centuries metal such as gold often combined with gemstones, has been the normal material for jewellery, but other materials such as glass, shells and other plant materials may be used.

A necklace is an article of jewellery that is worn around the neck. Necklaces may have been one of the earliest types of adornment worn by humans. They often serve ceremonial, religious, magical, or funerary purposes and are also used as symbols of wealth and status, given that they are commonly made of precious metals and stones.

Cloisonné is an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold. In recent centuries, vitreous enamel has been used, but inlays of cut gemstones, glass and other materials were also used during older periods; indeed cloisonné enamel very probably began as an easier imitation of cloisonné work using gems. The resulting objects can also be called cloisonné. The decoration is formed by first adding compartments to the metal object by soldering or affixing silver or gold as wires or thin strips placed on their edges. These remain visible in the finished piece, separating the different compartments of the enamel or inlays, which are often of several colors. Cloisonné enamel objects are worked on with enamel powder made into a paste, which then needs to be fired in a kiln. If gemstones or colored glass are used, the pieces need to be cut or ground into the shape of each cloison.

Filigree is a form of intricate metalwork used in jewellery and other small forms of metalwork.

A parure is a set of various items of matching jewelry, which rose to popularity in early 19th-century Europe.

The Pereshchepina Treasure is a major deposit of Turkic objects from the Migration Period.

The Oxus treasure is a collection of about 180 surviving pieces of metalwork in gold and silver, most relatively small, and around 200 coins, from the Achaemenid Persian period which were found by the Oxus river about 1877–1880. The exact place and date of the find remain unclear, but is often proposed as being near Kobadiyan. It is likely that many other pieces from the hoard were melted down for bullion; early reports suggest there were originally some 1500 coins, and mention types of metalwork that are not among the surviving pieces. The metalwork is believed to date from the sixth to fourth centuries BC, but the coins show a greater range, with some of those believed to belong to the treasure coming from around 200 BC. The most likely origin for the treasure is that it belonged to a temple, where votive offerings were deposited over a long period. How it came to be deposited is unknown.

The Middle Ages was a period that spanned approximately 1000 years and is normally restricted to Europe and the Byzantine Empire. The material remains we have from that time, including jewelry, can vary greatly depending on the place and time of their creation, especially as Christianity discouraged the burial of jewellery as grave goods, except for royalty and important clerics, who were often buried in their best clothes and wearing jewels. The main material used for jewellery design in antiquity and leading into the Middle Ages was gold. Many different techniques were used to create working surfaces and add decoration to those surfaces to produce the jewellery, including soldering, plating and gilding, repoussé, chasing, inlay, enamelling, filigree and granulation, stamping, striking and casting. Major stylistic phases include barbarian, Byzantine, Carolingian and Ottonian, Viking, and the Late Middle Ages, when Western European styles became relatively similar.

The Aegina Treasure or Aigina Treasure is an important Minoan gold hoard said to have been found on the island of Aegina, Greece. Since 1892, it has been part of the British Museum's collection. It is one of the most important groups of Minoan jewellery.

The Beaurains Treasure is the name of an important Roman hoard found in Beaurains, a suburb of the city of Arras, northern France in 1922. Soon after its discovery, much of the treasure was dispersed, to be sold on the antiquities market. The largest portion of the hoard can be found in the local museum in Arras and in the British Museum.

The Domagnano Treasure is an important Ostrogothic hoard found at Domagnano, Republic of San Marino in the late nineteenth century. The treasure is now divided among various institutions, including the Louvre Abu Dhabi, although the bulk of the hoard is currently held by the British Museum in London and the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg.

The Sutri Treasure is an important Lombardic hoard found at Sutri, Italy in the late nineteenth century that is currently in the collections of the British Museum in London.

The Artres Treasure is an important Merovingian hoard found at Artres, northern France in the nineteenth century. Most of the treasure is now in the collection of the British Museum in London.

The Canterbury Treasure is an important late Roman silver hoard found in the city of Canterbury, Kent, south-east England, ancient Durovernum Cantiacorum, in 1962, and now in the Roman Museum, Canterbury, Kent. Copies of the main items are also kept in the British Museum.

The Boscoreale Treasure is a large collection of exquisite silver and gold Roman objects discovered in the ruins of the ancient Villa della Pisanella at Boscoreale, near Pompeii, southern Italy. Consisting of over a hundred pieces of silverware, as well as gold coins and jewellery, it is now mostly kept at the Louvre Museum in Paris, although parts of the treasure can also be found at the British Museum.

The Tell el-Ajjul gold hoards are a collection of three hoards of Bronze Age gold jewellery found at the Canaanite site of Tell el-Ajjul in Gaza. Excavated by the British archaeologist Flinders Petrie in the 1930s, the collection is now mostly preserved at the British Museum in London and the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. The treasure ranks amongst the greatest Bronze Age finds in the Levant.

Ancient Roman jewelry was characterized by an interest in colored gemstones and glass in contrast with their Greek predecessors, who focused primarily on the production of high-quality metalwork by practiced artisans. Extensive control of Mediterranean territories provided an abundance of natural resources to utilize in jewelry making. Participation in trade allowed access to both semi-precious and precious stones that traveled down the Persian Silk Road from the East. Various types of jewelry were worn by different genders and social classes in Rome, and were used both for aesthetic purposes and to communicate social messages of status and wealth. Throughout the history of the Roman Empire, jewelry style and materials were influenced by Greek, Egyptian, and Etruscan jewelry.

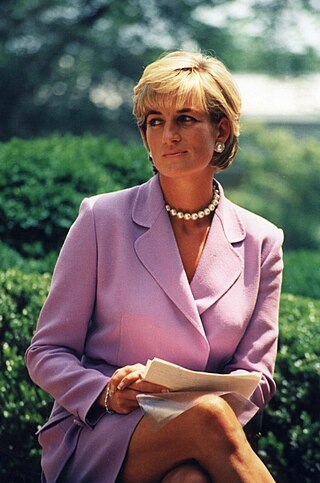

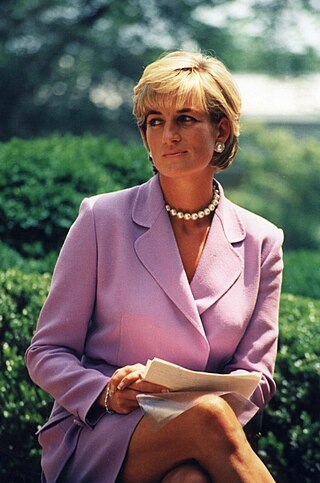

Diana, Princess of Wales, owned a collection of jewels both as a member of the British royal family and as a private individual. These were separate from the coronation and state regalia of the crown jewels. Most of her jewels were either presents from foreign royalty, on loan from Queen Elizabeth II, wedding presents, purchased by Diana herself, or heirlooms belonging to the Spencer family.