The sarcophagus ofEshmunazar II is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the grounds of an ancient necropolis southeast of the city of Sidon, in modern-day Lebanon, that contained the body of Eshmunazar II, Phoenician King of Sidon. One of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, with the other two belonging to Eshmunazar's father King Tabnit and to a woman, possibly Eshmunazar's mother Queen Amoashtart, it was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC. The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and a partial copy of it on the sarcophagus trough, around the curvature of the head. The lid inscription was of great significance upon its discovery as it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper and the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is today the second longest extant Phoenician inscription, after the Karatepe bilingual.

The Temple of Eshmun is an ancient place of worship dedicated to Eshmun, the Phoenician god of healing. It is located near the Awali river, 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) northeast of Sidon in southwestern Lebanon. The site was occupied from the 7th century BC to the 8th century AD, suggesting an integrated relationship with the nearby city of Sidon. Although originally constructed by Sidonian king Eshmunazar II in the Achaemenid era to celebrate the city's recovered wealth and stature, the temple complex was greatly expanded by Bodashtart, Yatonmilk and later monarchs. Because the continued expansion spanned many centuries of alternating independence and foreign hegemony, the sanctuary features a wealth of different architectural and decorative styles and influences.

Eshmunazar II was the Phoenician king of Sidon. He was the grandson of Eshmunazar I, and a vassal king of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Eshmunazar II succeeded his father Tabnit I who ruled for a short time and died before the birth of his son. Tabnit I was succeeded by his sister-wife Amoashtart who ruled alone until Eshmunazar II's birth, and then acted as his regent until the time he would have reached majority. Eshmunazar II died prematurely at the age of 14. He was succeeded by his cousin Bodashtart.

Bodashtart was a Phoenician ruler, who reigned as King of Sidon, the grandson of King Eshmunazar I, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He succeeded his cousin Eshmunazar II to the throne of Sidon, and scholars believe that he was succeeded by his son and proclaimed heir Yatonmilk.

The Byblian royal inscriptions are five inscriptions from Byblos written in an early type of Phoenician script, in the order of some of the kings of Byblos, all of which were discovered in the early 20th century.

The Thrones of Astarte are approximately a dozen ex-voto "cherubim" thrones found in ancient Phoenician temples in Lebanon, in particular in areas around Sidon, Tyre and Umm al-Amad. Many of the thrones have a similar style, with cherubim heads on winged lion bodies on either side. Images of the thrones are found in Phoenician sites around the Mediterranean, including an ivory plaque from Tel Megiddo (Israel), a relief from Hadrumetum (Tunisia) and a scarab from Tharros (Italy).

The Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum is a collection of ancient inscriptions in Semitic languages produced since the end of 2nd millennium BC until the rise of Islam. It was published in Latin. In a note recovered after his death, Ernest Renan stated that: "Of all I have done, it is the Corpus I like the most."

The Yehawmilk stele, de Clercq stele, or Byblos stele, also known as KAI 10 and CIS I 1, is a Phoenician inscription from c.450 BC found in Byblos at the end of Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. Yehawmilk, king of Byblos, dedicated the stele to the city’s protective goddess Ba'alat Gebal.

The Neirab steles are two 8th-century BC steles with Aramaic inscriptions found in 1891 in Al-Nayrab near Aleppo, Syria. They are currently in the Louvre. They were discovered in 1891 and acquired by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau for the Louvre on behalf of the Commission of the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum. The steles are made of black basalt, and the inscriptions note that they were funerary steles. The inscriptions are known as KAI 225 and KAI 226.

The Tayma stones, also Teima stones, were a number of Aramaic inscriptions found in Tayma, now northern Saudi Arabia. The first four inscriptions were found in 1878 and published in 1884, and subsequently included in the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum II as numbers 113-116. In 1972, ten further inscriptions were published, and in 1987 seven further inscriptions were published. Many of the inscriptions date to approximately the 5th and 6th centuries BCE.

The Anat Athena bilingual is a late fourth century BCE bilingual Greek-Phoenician inscription on a rock-cut stone found in the outskirts of the village of Larnakas tis Lapithou, Cyprus. It was discovered just above the village, at the foot of a conical agger, 6m high and 40 meters in circumference. It was originally found in c.1850.

Baalshillem I was a Phoenician King of Sidon, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He was succeeded by his son Abdamon to the throne of Sidon.

Baalshillem II was a Phoenician King of Sidon, and the great-grandson of Baalshillem I who founded the namesake dynasty. He succeeded Baana to the throne of Sidon, and was succeeded by his son Abdashtart I. The name Baalshillem means "recompense of Baal" in Phoenician.

The Abdmiskar cippus is a white marble cippus in obelisk form discovered in Sidon, Lebanon, dated to 300 BCE. Discovered in 1890 by Joseph-Ange Durighello.

The Tyre Cistern inscription is a Phoenician inscription on a white marble block discovered in the castle-palace of the Old City of Tyre, Lebanon in 1885 and acquired by Peter Julius Löytved, the Danish vice-consul in Beirut. It was the first Phoenician inscription discovered in modern times from Tyre.

The Abibaʻl Inscription is a Phoenician inscription from Byblos on the base of a throne on which a statue of Sheshonq I was placed. It is held at the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.

The Baalshamem inscription is a Phoenician inscription discovered in 1860–61 at Umm al-Amad, Lebanon, the longest of three inscriptions found there during Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. All three inscriptions were found on the north side of the hill; this inscription was found in the foundation of one of the ruined houses covering the hill.

The Phoenician Adoration steles are a number of Phoenician and Punic steles depicting the adoration gesture (orans).

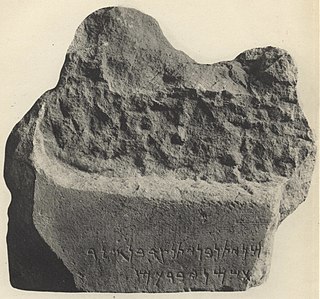

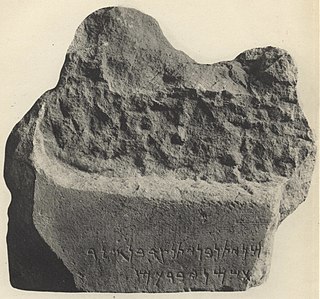

The Eshmun inscription is a Phoenician inscription on a fragment of grey-blue limestone found at the Temple of Eshmun in 1901. It is also known as RES 297. Some elements of the writing have been said to be similar to the Athenian Greek-Phoenician inscriptions. Today, it is held in the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul.

Hiram's Tomb is a large limestone sarcophagus and pedestal located approximately 6 km southeast of Tyre, Lebanon, near the village of Hanaouay on the road to Qana.