The Mariel boatlift was a mass emigration of Cubans who traveled from Cuba's Mariel Harbor to the United States between April 15 and October 31, 1980. The term "Marielito" is used to refer to these refugees in both Spanish and English. While the exodus was triggered by a sharp downturn in the Cuban economy, it followed on the heels of generations of Cubans who had immigrated to the United States in the preceding decades.

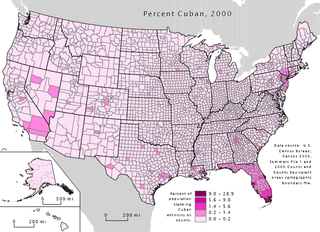

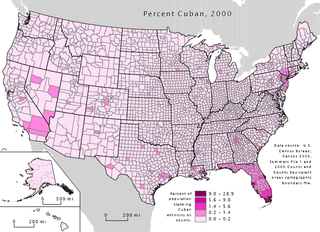

Cuban Americans are Americans who immigrated from or are descended from immigrants from Cuba, regardless of racial or ethnic origin. As of 2023, Cuban Americans were the fourth largest Hispanic and Latino American group in the United States after Mexican Americans, Stateside Puerto Ricans and Salvadoran Americans.

Brothers to the Rescue is a Miami-based activist nonprofit organization headed by José Basulto. Formed by Cuban exiles, the group is widely known for its opposition to the Cuban government and its former leader Fidel Castro. The group describes itself as a humanitarian organization aiming to assist and rescue raft refugees emigrating from Cuba and to "support the efforts of the Cuban people to free themselves from dictatorship through the use of active non-violence". Brothers to the Rescue, Inc., was founded in May 1991 "after several pilots were touched by the death of" fifteen-year-old Gregorio Perez Ricardo, who "fleeing Castro's Cuba on a raft, perished of severe dehydration in the hands of U.S. Coast Guard officers who were attempting to save his life."

The wet feet, dry feet policy or wet foot, dry foot policy was the name given to a former interpretation of the 1995 revision of the application of the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 that essentially says that anyone who emigrated from Cuba and entered the United States would be allowed to pursue residency a year later. Prior to 1995, the U.S. government allowed all Cubans who reached U.S. territorial waters to remain in the U.S. After talks with the Cuban government, the Clinton administration came to an agreement with Cuba that it would stop admitting people intercepted in U.S. waters.

The Cuban exodus is the mass emigration of Cubans from the island of Cuba after the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Throughout the exodus, millions of Cubans from diverse social positions within Cuban society emigrated within various emigration waves, due to political repression and disillusionment with life in Cuba. Between 1959 and 2023, some 2.9 million Cubans emigrated from Cuba.

Balseros is a 2002 Catalan documentary co-directed by Carles Bosch and Josep Maria Domènech about Cubans leaving during the Período Especial.

Cuban immigration has greatly affected Miami-Dade County since 1959, creating what is known as "Cuban Miami." However, Miami reflects global trends as well, such as the growing trends of multiculturalism and multiracialism; this reflects the way in which international politics shape local communities.

Operation Sea Signal was a United States Department of Defense operation in the Caribbean in response to an influx of Cuban and Haitian migrants attempting to gain asylum in the United States. As a result, the migrants became refugees at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. The operation took place from May 1992 to February 1996 under Joint Task Force 160. The task force processed over 50,000 refugees as part of the operation. The U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Navy rescued refugees from the sea and other migrants attempted to cross the landmine field that then separated the U.S. and Cuban military areas. Soldiers, Airmen, and Marines provided refugee camp security at Guantanamo Bay, and ship security on board the Coast Guard cutters. This mass exodus led to the U.S. immigration implementation of the Wet Feet Dry Feet Policy. The mass Cuban exodus of 1994 was similar to the Mariel boatlift in 1980.

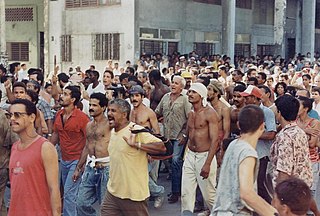

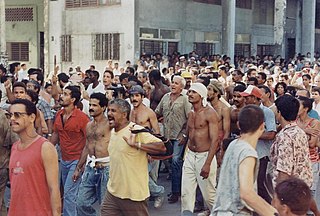

The Maleconazo was a protest on 5 August 1994, in which thousands of Cubans took to the streets around the Malecón in Havana to demand freedom and express frustration with the government. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Cuba fell into a crippling economic crisis that had many citizens looking to flee the island. On the day of the protest, the Cuban police blocked people from boarding tugboats leaving Havana, prompting thousands of citizens to storm the streets in the largest anti-government demonstration Cuba had seen since the Cuban Revolution. In the following weeks, President Fidel Castro quelled the frustration by opening the doors of the country and allowing Cubans to leave, which had a significant impact on Cuba's relationship with the United States moving forward.

Freedom Flights transported Cubans to Miami twice daily, five times per week from 1965 to 1973. Its budget was about $12 million and it brought an estimated 300,000 refugees, making it the "largest airborne refugee operation in American history." The Freedom Flights were an important and unusual chapter of cooperation in the history of Cuban-American foreign relations, which is otherwise characterized by mutual distrust. The program changed the ethnic makeup of Miami and fueled the growth of the Cuban-American enclave there.

Lizbet Martínez is a Cuban violinist and English teacher at M.A. Milam K-8 Center.

Cuban immigration to the United States, for the most part, occurred in two periods: the first series of immigration of wealthy Cuban Americans to the United States resulted from Cubans establishing cigar factories in Tampa and from attempts to overthrow Spanish colonial rule by the movement led by José Martí, the second to escape from Communist rule under Fidel Castro following the Cuban Revolution. Massive Cuban migration to Miami during the second series led to major demographic and cultural changes in Miami. There was also economic emigration, particularly during the Great Depression in the 1930s. As of 2019, there were 1,359,990 Cubans in the United States.

The 1994 Cuban rafter crisis which is also known as the 1994 Cuban raft exodus or the Balsero crisis was the emigration of more than 35,069 Cubans to the United States. The exodus occurred over five weeks following rioting in Cuba; Fidel Castro announced in response that anyone who wished to leave the country could do so without any hindrance. Fearing a major exodus, the Clinton administration would mandate that all rafters captured at sea be detained at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.

"Refugees as weapons" is a term used to describe a hostile government organizing, or threatening to organize, a sudden influx of refugees into another country or political entity with the intent of causing political disturbances in that entity. The responsible country usually seeks to extract concessions from the targeted country and achieve some political, military, and/or economic objective.

The emigration of Cubans, from the 1959 Cuban Revolution to October of 1962, has been dubbed the Golden exile and the first emigration wave in the greater Cuban exile. The exodus was referred to as the "Golden exile" because of the mainly upper and middle class character of the emigrants. After the success of the revolution various Cubans who had allied themselves or worked with the overthrown Batista regime fled the country. Later as the Fidel Castro government began nationalizing industries many Cuban professionals would flee the island. This period of the Cuban exile is also referred to as the Historical exile, mainly by those who emigrated during this period.

Haitian boat people are refugees from Haiti who flee the country by boat, usually to South Florida and sometimes the Bahamas.

A Cuban exile is a person who emigrated from Cuba in the Cuban exodus. Exiles have various differing experiences as emigrants depending on when they migrated during the exodus.

Cuban boat people mainly refers to refugees who flee Cuba by boat and ship to the United States.

The idea of the Cuba de ayer is a mythologized idyllic view of Cuba before the overthrow of the Batista government in the Cuban Revolution. This idealized vision of pre-revolutionary Cuba typically reinforces the ideas that Cuba before 1959 was an elegant, sophisticated, and largely white country that was ruined by the government of Fidel Castro. The Cuban exiles who fled after 1959 are viewed as majorly white, and had no general desire to leave Cuba but did so to flee tyranny.

The 2021–2024 Cuban migration crisis refers to an ongoing event characterized by a significant surge of Cuban nationals leaving the country, mostly to the United States, due to a combination of factors, including economic hardships and political uncertainties in their homeland. The crisis has resulted in a notable increase in Cuban encounters at the United States' southern border, with many attempting to cross into the country through both regular border crossings and sea arrivals, particularly in South Florida. The mass exodus has posed humanitarian, social, and political challenges for both Cuba and the U.S., prompting discussions and negotiations between the two nations to address the crisis and manage the flow of migrants. It has been described as the largest mass emigration in Cuba's history. It is estimated that nearly 850,000 Cubans sought refuge into the United States between 2021-2024, depleting Cuba's population by nearly 8%. It is estimated that 50% of the new Cuban arrivals between 2021-2024 (425,000), have settled in Miami-Dade County.