The island of Cuba was inhabited by various Native American cultures prior to the arrival of the explorer Christopher Columbus in 1492. After his arrival, Spain conquered Cuba and appointed Spanish governors to rule in Havana. The administrators in Cuba were subject to the Viceroy of New Spain and the local authorities in Hispaniola. In 1762–63, Havana was briefly occupied by Britain, before being returned to Spain in exchange for Florida. A series of rebellions between 1868 and 1898, led by General Máximo Gómez, failed to end Spanish rule and claimed the lives of 49,000 Cuban guerrillas and 126,000 Spanish soldiers. However, the Spanish–American War resulted in a Spanish withdrawal from the island in 1898, and following three and a half years of subsequent US military rule, Cuba gained formal independence in 1902.

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar was a Cuban military officer and politician who played a dominant role in Cuban politics from his initial rise to power as part of the 1933 Revolt of the Sergeants until his overthrow in the Cuban Revolution in 1959. He served as elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944, and military dictator from 1952 to his 1959 resignation.

Operation Peter Pan was a clandestine exodus of over 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban minors ages 6 to 18 to the United States over a two-year span from 1960 to 1962. They were sent by parents who feared, on the basis of unsubstantiated rumors, that Fidel Castro and the Communist party were planning to terminate parental rights and place minors in alleged "communist indoctrination centers", commonly referred to as the Patria Potestad. No such actions by the Castro regime ever took place.

The Venceremos Brigade is an international organization founded in 1969 by members of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and officials of the Republic of Cuba. It was formed as a coalition of young people to show solidarity with the Cuban Revolution by working side by side with Cuban workers, challenging U.S. policies towards Cuba, including the United States embargo against Cuba. The yearly brigade trips, which as of 2010 have brought more than 9,000 people to Cuba, continue today and are coordinated with the Pastors For Peace Friendship Caravans to Cuba. The 48th Brigade travelled to Cuba in July 2017.

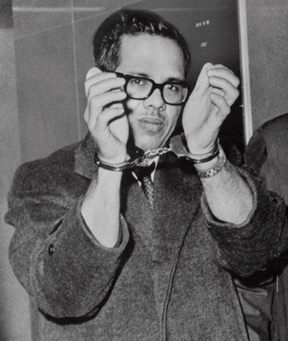

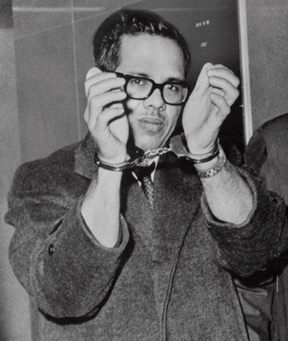

Orlando Bosch Ávila was a Cuban exile militant, who headed the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations (CORU), described by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation as a terrorist organization. Born in Cuba, Bosch attended medical school at the University of Havana, where he befriended Fidel Castro. He worked as a doctor in Santa Clara Province in the 1950s, but moved to Miami in 1960 after he stopped supporting the Cuban Revolution.

Rolando Arcadio Masferrer Rojas, better known simply as Rolando Masferrer, was a Cuban henchman, lawyer, congressman, newspaper publisher and a political activist.

Lt. General José Antonio de la Caridad Maceo y Grajales was a Cuban general and second-in-command of the Cuban Army of Independence.

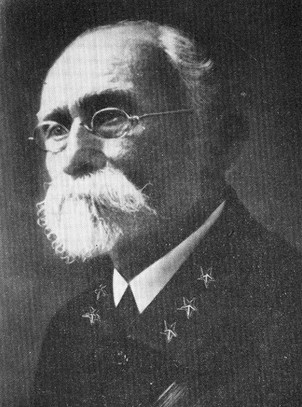

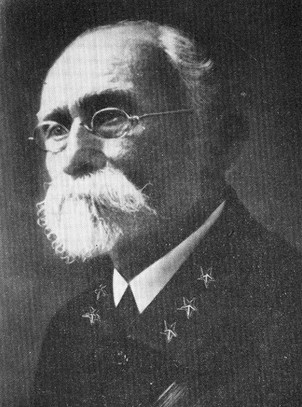

Máximo Gómez y Báez was a Cuban-Dominican Generalissimo in Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains and torching the Spanish loyalists' property and sugar plantations—including many owned by Americans. He greatly increased the efficacy of the attacks by torturing and killing not only Spanish soldiers, but also Spanish sympathizers and especially Cubans loyal to Spain. By the time the Spanish–American War broke out in April 1898, the rebellion was virtually defeated in most of Western Cuba, with only a few operating pockets in the center and the east. He refused to join forces with the Spanish in fighting off the United States, and he retired to the Quinta de los Molinos, a luxury villa outside of Havana after the war's end formerly used by captains generals as summer residence.

Luis Clemente Posada Carriles was a Cuban exile militant and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agent. He was considered a terrorist by the United States' Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Government of Cuba, among others.

The Cuban exodus is the mass emigration of Cubans from the island of Cuba after the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Throughout the exodus, millions of Cubans from diverse social positions within Cuban society emigrated within various emigration waves, due to political repression and disillusionment with life in Cuba. Between 1959 and 2023, some 2.9 million Cubans emigrated from Cuba.

Alpha 66 is an anti-Castro paramilitary organization. The group was originally formed by Cuban exiles in the early 1960s and was most active in the late 1970s and 1980s. Its activities declined in the 1980s.

Polita Grau was the First Lady of Cuba, a Cuban political prisoner, and the "godmother" of Operation Peter Pan, also known as Operación Pedro Pan, a program to help children leave Cuba. Operation Peter Pan involved the Roman Catholic Church and Monsignor Bryan O. Walsh from 1960 to 1962, which were involved in encouraging Cuban parents to send their children to live with U.S families to rescue them from Communism.

Dr. Bernardo Benes Baikowitz was a prominent Jewish Cuban lawyer, banker, journalist and civic leader, who was responsible for freeing 3,600 Cuban political prisoners in 1978.

Alfredo Joaquin González Durán is a Cuban-born lawyer and an advocate for dialogue as a way to bring regime change in Cuba. His views are considered controversial in some parts of the Cuban exile community in Miami.

Lourdes Casal was an important poet and activist for the Cuban community. She was internationally known for her contributions to psychology, writing, and Cuban politics. Born and raised in Cuba, she sought exile in New York because of Cuban communist rule. Casal received a master's degree in psychology in 1962 and later, a doctorate in 1975 from the New School for Social Research. She wrote the book El caso Padilla: literatura y revolucion en Cuba, which illustrated the failing relationship between writers and Cuban officials. A year later, she co-founded a journal named Nueva Generation which focused on creating dialogue on relationships between Cubans living abroad and on the island. Casal earned notoriety by attempting to reconcile Cuban exiles in the United States. She was instrumental in organizing a dialogue between Cuban immigrants and Fidel Castro, which led to the release of thousands of Cuban prisoners. She was the first Cuban-American to receive the Casa de las Américas Prize, which was awarded to her posthumously in 1981.

Jesús A. Permuy is a Cuban-American architect, urban planner, human rights activist, art collector, and businessman. He is known for an extensive career of community projects and initiatives in Florida, Washington, D.C., and Latin America.

The emigration of Cubans, from the 1959 Cuban Revolution to October of 1962, has been dubbed the Golden exile and the first emigration wave in the greater Cuban exile. The exodus was referred to as the "Golden exile" because of the mainly upper and middle class character of the emigrants. After the success of the revolution various Cubans who had allied themselves or worked with the overthrown Batista regime fled the country. Later as the Fidel Castro government began nationalizing industries many Cuban professionals would flee the island. This period of the Cuban exile is also referred to as the Historical exile, mainly by those who emigrated during this period.

The Antonio Maceo Brigade was a political organization in the mid-1970s composed of Cuban Americans that demanded the right of Cuban exiles to travel to Cuba and to establish good relations with the Cuban government. The group was mainly composed of young Cuban Americans that had developed leftist sympathies from experiences in the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement, and were generally critical of anti-Castro rhetoric. The group was invited to Cuba personally by Fidel Castro. The visit brought a brief period of warmer Cuba-United States relations and brought attention to the Cuban-American left.

In 1978 negotiations known as El Diálogo occurred between Cuban exile groups and the Cuban government that resulted in the release of political prisoners.

Felipe Rivero was an anti-Castro Cuban exile who fought against the regime of Fidel Castro as a member of Brigade 2506 in the landings at Playa Girón during the Bay of Pigs Invasion. Rivero soon became an ideological leader of the anti-Castro movement. Rivero was the director, and one of seven creators of the Cuban Nationalist Association, which was the first Cuban exile organization to use terror tactics. The MNC was responsible for several terrorist bombings throughout the Americas, including an attempted assassination of Che Guevara during an attack on the Headquarters of the United Nations, and the bombing of the Cuban embassy in Ottawa. Later in life, Rivero became a radio host at WRHC (AM), where he was known to the community of Little Havana as a Holocaust denier and Fascist.