The Elephantine Papyri and Ostraca consist of thousands of documents from the Egyptian border fortresses of Elephantine and Aswan, which yielded hundreds of papyri and ostraca in hieratic and demotic Egyptian, Aramaic, Koine Greek, Latin and Coptic, spanning a period of 100 years in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE. The documents include letters and legal contracts from family and other archives and are thus an invaluable source of knowledge for scholars of varied disciplines such as epistolography, law, society, religion, language, and onomastics. The Elephantine documents include letters and legal contracts from family and other archives: divorce documents, the manumission of enslaved people, and other business. The dry soil of Upper Egypt preserved the documents.

Zincirli Höyük is an archaeological site located in the Anti-Taurus Mountains of modern Turkey's Gaziantep Province. During its time under the control of the Neo-Assyrian Empire it was called, by them, Sam'al. It was founded at least as far back as the Early Bronze Age and thrived between 3000 and 2000 BC, and on the highest part of the upper mound was found a walled citadel of the Middle Bronze Age.

Christian Palestinian Aramaic was a Western Aramaic dialect used by the Melkite Christian community, predominantly of Jewish descent, in Palestine, Transjordan and Sinai between the fifth and thirteenth centuries. It is preserved in inscriptions, manuscripts and amulets. All the medieval Western Aramaic dialects are defined by religious community. CPA is closely related to its counterparts, Jewish Palestinian Aramaic (JPA) and Samaritan Aramaic (SA). CPA shows a specific vocabulary that is often not paralleled in the adjacent Western Aramaic dialects.

The Sfire or Sefire steles are three 8th-century BCE basalt stelae containing Aramaic inscriptions discovered near Al-Safirah ("Sfire") near Aleppo, Syria. The Sefire treaty inscriptions are the three inscriptions on the steles; they are known as KAI 222-224. A fourth stele, possibly from Sfire, is known as KAI 227.

The Stele of Zakkur is a royal stele of King Zakkur of Hamath and Luhuti in the province Nuhašše of Syria, who ruled around 785 BC.

The Kilamuwa Stele is a 9th-century BC stele of King Kilamuwa, from the Kingdom of Bit-Gabbari. He claims to have succeeded where his ancestors had failed, in providing for his kingdom. The inscription is known as KAI 24.

Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften, or KAI, is the standard source for the original text of Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions not contained in the Hebrew Bible.

The Melqart stele, also known as the Ben-Hadad or Bir-Hadad stele is an Aramaic stele which was created during the 9th century BCE and was discovered in 1939 in Roman ruins in Bureij Syria. The Old Aramaic inscription is known as KAI 201; its five lines reads:

“The stele which Bar-Had-

-ad, son of [...]

king of Aram, erected to his Lord Melqar-

-t, to whom he made a vow and who heard his voi-

-ce.”

The Carpentras Stele is a stele found at Carpentras in southern France in 1704 that contains the first published inscription written in the Phoenician alphabet, and the first ever identified as Aramaic. It remains in Carpentras, at the Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, in a "dark corner" on the first floor. Older Aramaic texts were found since the 9th century BC, but this one is the first Aramaic text to be published in Europe. It is known as KAI 269, CIS II 141 and TAD C20.5.

The Sarıaydın inscription is an Aramaic inscription found in situ in 1892 near the village of Sarıaydın in Southern Anatolia. It is also known as the Sarıaydın Hunting inscription or the Cilician Hunting inscription. It was discovered on the Austrian expedition to Cilicia of Rudolf Heberdey and Adolf Wilhelm.

The Hadad Statue is an 8th-century BC stele of King Panamuwa I, from the Kingdom of Bit-Gabbari in Sam'al. It is currently occupies a prominent position in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.

The Panamuwa II inscription is a 9th-century BC stele of King Panamuwa II, from the Kingdom of Bit-Gabbari in Sam'al. It currently occupies a prominent position in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.

The Neirab steles are two 8th-century BC steles with Aramaic inscriptions found in 1891 in Al-Nayrab near Aleppo, Syria. They are currently in the Louvre. They were discovered in 1891 and acquired by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau for the Louvre on behalf of the Commission of the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum. The steles are made of black basalt, and the inscriptions note that they were funerary steles. The inscriptions are known as KAI 225 and KAI 226.

The Tayma stones, also Teima or Tema stones, were a number of Aramaic inscriptions found in Tayma, now northern Saudi Arabia. The first four inscriptions were found in 1878 and published in 1884, and included in the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum II as numbers 113-116. In 1972, ten further inscriptions were published. In 1987 seven further inscriptions were published. Many of the inscriptions date to approximately the 5th and 6th centuries BCE.

The Gözne Boundary Stone is an Aramaic inscription found in situ in 1907 near the village of Gözne in Southern Anatolia, by John Renwick Metheny. It was first published by James Alan Montgomery.

The Idalion Temple inscriptions are six Phoenician inscriptions found by Robert Hamilton Lang in his excavations at the Temple of Idalium in 1869, whose work there had been inspired by the discovery of the Idalion Tablet in 1850. The most famous of these inscriptions is known as the Idalion bilingual. The Phoenician inscriptions are known as KAI 38-40 and CIS I 89-94.

Rʻuth-Assor, also transliterated Rʻuṯassor, Rʻūṯ’assor or Rʻūṯassor, was a local Assyrian king or city-lord in the early 2nd century AD, ruling the city of Assur under the suzerainty of the Parthian Empire. The continued veneration of Ashur and other Assyrian gods under Rʻuth-Assor and his predecessors and successors, as well as their stelae greatly resembling those erected under by the old kings of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, suggests that Rʻuth-Assor and the other rulers of Assur during this time saw themselves as the continuation of the ancient line of Assyrian kings.

The Farasa bilingual inscription, originally known as the Zindji-Dérè or Zindji-Dara inscription, is a bilingual Greek-Aramaic inscription found along the Zamantı River outside Farasa, Cappadocia, known today as Çamlıca village in Yahyalı, Kayseri). It was identified in modern times by Anastasios Levidhis of the town of Zindji-Dérè, and first published in 1905 by Josef Markwart.

The Hasanbeyli inscription is a Phoenician inscription on a basalt stone discovered in the village of Hasanbeyli, on the western slopes of the Amanus Mountains, in 1894.

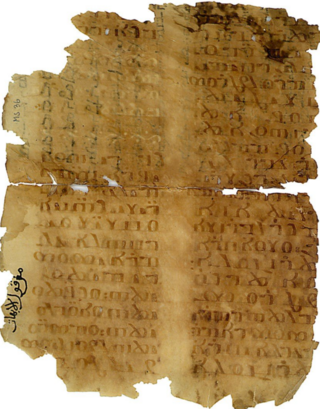

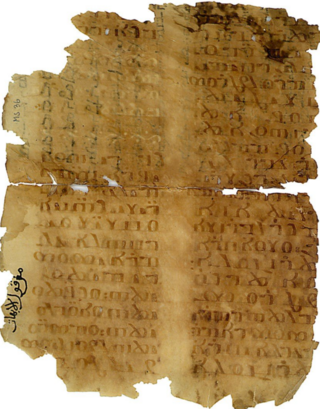

The Behistun papyrus, formally known as Berlin Papyrus P. 13447, is an Aramaic-Egyptian fragmentary partial copy of the Behistun inscription, and one of the Elephantine papyri discovered during the German excavations between 1906 and 1908.