The unification of Italy, also known as the Risorgimento, was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of Sardinia, resulting in the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. Inspired by the rebellions in the 1820s and 1830s against the outcome of the Congress of Vienna, the unification process was precipitated by the Revolutions of 1848, and reached completion in 1870 after the capture of Rome and its designation as the capital of the Kingdom of Italy.

The Roman Republic was a short-lived state declared on 9 February 1849, when the government of the Papal States was temporarily replaced by a republican government due to Pope Pius IX's departure to Gaeta. The republic was led by Carlo Armellini, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Aurelio Saffi. Together they formed a triumvirate, a reflection of a form of government during the first century BC crisis of the Roman Republic.

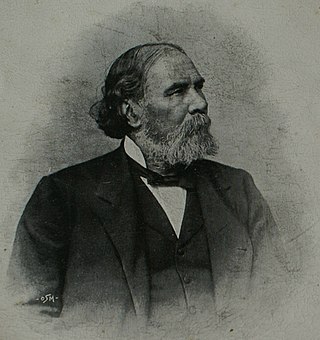

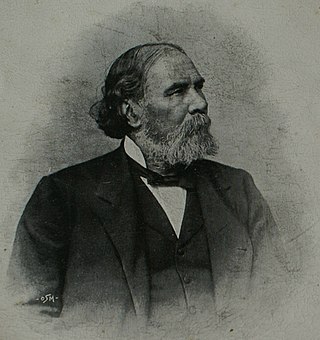

Agostino Depretis was an Italian statesman and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Italy for several stretches between 1876 and 1887, and was leader of the Historical Left parliamentary group for more than a decade. He is the fourth-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history, after Benito Mussolini, Giovanni Giolitti and Silvio Berlusconi, and at the time of his death he was the longest-served. Depretis is widely considered one of the most powerful and important politicians in Italian history, having enacted numerous reforms that modernized Italy, such as expanding male suffrage and free education.

Giovanni Nicotera was an Italian patriot and politician. His surname is pronounced as, with stress on the second syllable.

The Expedition of the Thousand was an event of the unification of Italy that took place in 1860. A corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto al Mare near Genoa and landed in Marsala, Sicily, in order to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the Spanish House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. The name of the expedition derives from the initial number of participants, which was around 1,000 people.

The Roman question was a dispute regarding the temporal power of the popes as rulers of a civil territory in the context of the Italian Risorgimento. It ended with the Lateran Pacts between King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and Pope Pius XI in 1929.

This is a timeline of the unification of Italy.

The First Italian War of Independence, part of the Italian Unification (Risorgimento), was fought by the Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) and Italian volunteers against the Austrian Empire and other conservative states from 23 March 1848 to 22 August 1849 in the Italian Peninsula.

The Third Italian War of Independence was a war between the Kingdom of Italy and the Austrian Empire fought between June and August 1866. The conflict paralleled the Austro-Prussian War and resulted in Austria conceding the region of Venetia to France, which was later annexed by Italy after a plebiscite. Italy's acquisition of this wealthy and populous territory represented a major step in the Unification of Italy.

The Capture of Rome occurred on 20 September 1870, as forces of the Kingdom of Italy took control of the city and of the Papal States. After a plebiscite held on 2 October 1870, Rome was officially made capital of Italy on 3 February 1871, completing the unification of Italy (Risorgimento).

The Battle of the Volturno refers to a series of military clashes between Giuseppe Garibaldi's volunteers and the troops of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies occurring around the River Volturno, between the cities of Capua and Caserta in northern Campania, in September and October 1860. The main battle took place on 1 October 1860 between 30,000 Garibaldines and 25,000 Bourbon troops (Neapolitans).

The Battle of Mentana was fought on November 3, 1867, near the village of Mentana, located north-east of Rome, between French-Papal troops and the Italian volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi. Garibaldi and his troops were attempting to capture Rome, then the main center of the peninsula still outside of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy. The battle ended in a victory by the French-Papal troops.

Amilcare Cipriani was an Italian socialist, anarchist and patriot.

Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. He contributed to Italian unification (Risorgimento) and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. He is considered to be one of Italy's "fathers of the fatherland", along with Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy and Giuseppe Mazzini. Garibaldi is also known as the "Hero of the Two Worlds" because of his military enterprises in South America and Europe.

Agostino Bertani was an Italian revolutionary and physician during Italian unification.

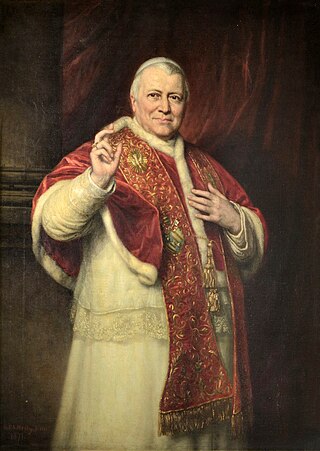

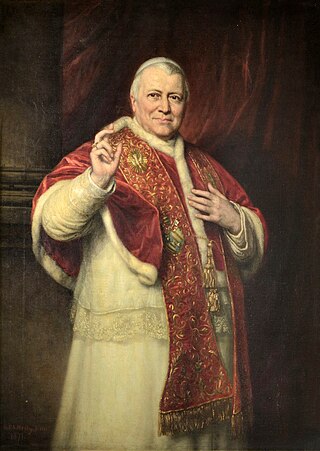

Foreign relations between Pope Pius IX and Italy were characterized by an extensive political and diplomatic conflict over Italian unification and the subsequent status of Rome after the victory of the liberal revolutionaries.

The Papal States under Pope Pius IX assumed a much more modern and secular character than had been seen under previous pontificates, and yet this progressive modernization was not nearly sufficient in resisting the tide of political liberalization and unification in Italy during the middle of the 19th century.

Francesco Nullo was an Italian patriot, military officer and merchant, and a close friend and confidant of Giuseppe Garibaldi. He supported independence movements in Italy and Poland. He was a participant in the Five Days of Milan and other events of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states, Sicilian Expedition of the Thousand in 1860 and the Polish January Uprising in 1863. His military career ended with him receiving the rank of general in Poland, shortly before his death in the Battle of Krzykawka.

Domenico Menotti Garibaldi was an Italian soldier and politician who was the eldest son of Giuseppe Garibaldi and Anita Garibaldi. He fought in the Second and Third wars of Italian Unification, and organized the Garibaldi Legion, a unit of Italian volunteers who fought for Polish independence in the January Uprising of 1863. He also served in the Italian Chamber of Deputies.