The Burma campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of Burma. It was part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II and primarily involved forces of the Allies against the invading forces of the Empire of Japan. Imperial Japan was supported by the Thai Phayap Army, as well as two collaborationist independence movements and armies. Nominally independent puppet states were established in the conquered areas and some territories were annexed by Thailand. In 1942 and 1943, the international Allied force in British India launched several failed offensives to retake lost territories. Fighting intensified in 1944, and British Empire forces peaked at around 1 million land and air forces. These forces were drawn primarily from British India, with British Army forces, 100,000 East and West African colonial troops, and smaller numbers of land and air forces from several other Dominions and Colonies. These additional forces allowed the Allied recapture of Burma in 1945.

The Battle of Kohima was the turning point of the Japanese U-Go offensive into India in 1944 during the Second World War. The battle took place in three stages from 4 April to 22 June 1944 around the town of Kohima, now the capital city of Nagaland in Northeast India. From 3 to 16 April, the Japanese attempted to capture Kohima ridge, a feature which dominated the road by which the besieged British and Indian troops of IV Corps at Imphal were supplied. By mid-April, the small British and British Indian force at Kohima was relieved.

The Battle of Imphal took place in the region around the city of Imphal, the capital of the state of Manipur in Northeast India from March until July 1944. Japanese armies attempted to destroy the Allied forces at Imphal and invade India, but were driven back into Burma with heavy losses. Together with the simultaneous Battle of Kohima on the road by which the encircled Allied forces at Imphal were relieved, the battle was the turning point of the Burma campaign, part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II. The Japanese defeat at Kohima and Imphal was the largest up until that time, with many of the Japanese deaths resulting from starvation, disease and exhaustion suffered during their retreat. According to voting in a contest run by the British National Army Museum, the Battle of Imphal was bestowed as Britain's Greatest Battle in 2013.

The 5th Infantry Division is an infantry division of the Indian Army. It was raised during the second world war and fought in several theatres of war and was nicknamed the "Ball of Fire". It was one of the few Allied divisions to fight against three different armies - the Italian, German and Japanese armies.

General Sir Montagu George North Stopford, was a senior British Army officer who fought during both the First and Second World Wars. The latter he served in with distinction, commanding XXXIII Indian Corps in the Far East, where he served under General Sir William Slim, and played a significant role in the Burma Campaign, specifically during the Battle of Kohima in mid-1944.

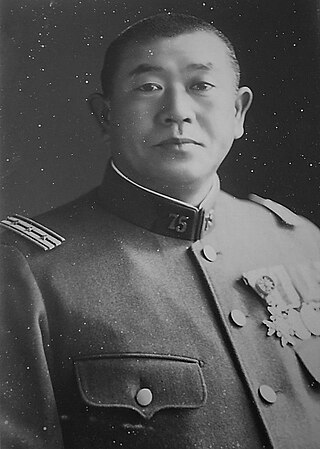

Kōtoku Satō was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II.

The 7th Infantry Division is a war-formed infantry division, part of the British Indian Army that saw service in the Burma Campaign.

The 33rd Division was an infantry division of the Imperial Japanese Army. Its call sign was the Bow Division. The 33rd Division was raised in Utsunomiya, Tochigi prefecture, simultaneously with 32nd, 34th, 35th, 36th and 37th Divisions. Its headquarters were initially in Sendai. It was raised from conscripts largely from the northern Kantō prefectures of Tochigi, Ibaraki and Gunma.

The 31st Division was an infantry division of the Imperial Japanese Army. Its call sign was the Furious Division. The 31st Division was raised during World War II in Bangkok, Thailand, on March 22, 1943, out of Kawaguchi Detachment and parts of the 13th, 40th and 116th divisions. The 31st division was initially assigned to 15th army.

Lieutenant General Sir Harold Rawdon Briggs, was a senior British Indian Army officer, active during the First World War, Second World War and the Malayan Emergency.

The U Go offensive, or Operation C, was the Japanese offensive launched in March 1944 against forces of the British Empire in the northeast Indian regions of Manipur and the Naga Hills. Aimed at the Brahmaputra Valley, through the towns of Imphal and Kohima, the offensive along with the overlapping Ha Go offensive was one of the last Japanese offensives during the Second World War. The offensive culminated in the Battles of Imphal and Kohima, where the Japanese and their allies were first held and then pushed back.

The fighting in the Burma campaign in 1944 was among the most severe in the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II. It took place along the borders between Burma and India, and Burma and China, and involved the British Commonwealth, Chinese and United States forces, against the forces of Imperial Japan and the Indian National Army. British Commonwealth land forces were drawn primarily from the United Kingdom, British India and Africa.

The Battle of Shangshak took place in Manipur in the forested and mountainous frontier area between India and Burma, from 20 March to 26 March 1944. The Japanese drove a parachute brigade of the British Indian Army from its positions with heavy casualties, but suffered heavy casualties themselves. The delay imposed on the Japanese by the battle allowed British and Indian reinforcements to reach the vital position at Kohima before the Japanese.

The British Indian XXXIII Corps was a corps-sized formation of the Indian Army during the Second World War. It was disbanded and the headquarters was recreated as an Army headquarters in 1945.

The 161st Indian Infantry Brigade was an infantry brigade formation of the Indian Army during World War II. As part of the arrangements for the independence and partition of British India the brigade was allocated to India and became the 161st Infantry Brigade in the army of the newly independent India.

Kohima War Cemetery is a memorial dedicated to soldiers of the 2nd British Division of the Allied Forces who died in the Second World War at Kohima, the capital of the Indian state of Nagaland in April 1944. The soldiers died on the battleground of Garrison Hill in the tennis court area of the Deputy Commissioner's residence. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which maintains this cemetery among many others in the world, there are 1,420 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War at this cemetery, and a memorial to an additional 917 Hindu and Sikh soldiers who were cremated in accordance with their faith. The memorial was inaugurated by Field Marshal Sir William Slim, then Commander of the 14th Army in Burma.

The Imphal War Cemetery is located in Imphal, the capital of the Indian state of Manipur, in Northeast India, which has an international border with upper Burma. The cemetery has 1,600 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War and is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Many of the people buried in the cemetery were killed during the Battle of Kohima and Imphal.

The Chamar Regiment was an infantry regiment among the units raised by the British during World War II to increase the strength of the Indian Army during World War II.

The 118th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, was an air defence unit of the British Army during World War II. Initially raised as an infantry battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment in 1940, it transferred to the Royal Artillery in 1942. It served in Home Forces and then went to Assam to defend Fourteenth Army's vital bases and airfields during the Burma Campaign until it was broken up in 1944.

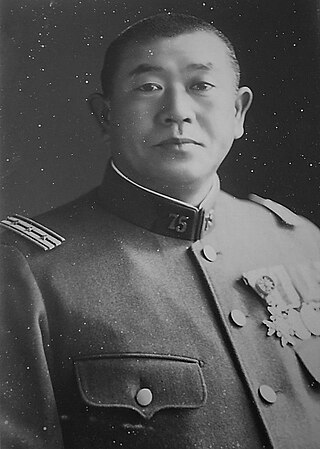

Shigesaburō Miyazaki was a Japanese major general of the Imperial Japanese Army who was notable for commanding the Japanese 31st Division in the Burma Campaign of 1944. His eldest son was Shigeki Miyazaki who was the former president of Meiji University.