Effigy Mounds National Monument preserves more than 200 prehistoric mounds built by pre-Columbian Mound Builder cultures, mostly in the first millennium CE, during the later part of the Woodland period of pre-Columbian North America. Numerous effigy mounds are shaped like animals, including bears and birds.

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from 100 BCE to 500 CE, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society but a widely dispersed set of populations connected by a common network of trade routes.

The Great Serpent Mound is a 1,348-feet-long (411 m), three-feet-high prehistoric effigy mound located in Peebles, Ohio. It was built on what is known as the Serpent Mound crater plateau, running along the Ohio Brush Creek in Adams County, Ohio. The mound is the largest serpent effigy known in the world.

Fort Ancient is a name for a Native American culture that flourished from c. 1000–1750 CE and predominantly inhabited land near the Ohio River valley in the areas of modern-day southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, southeastern Indiana and western West Virginia. Although a contemporary of the Mississippian culture, they are often considered a "sister culture" and distinguished from the Mississippian culture. While far from agreed upon, there is evidence to suggest that the Fort Ancient Culture were not the direct descendants of the Hopewellian Culture. It is suspected that the Fort Ancient Culture introduced maize agriculture to Ohio. The Fort Ancient Culture were most likely the builders of the Great Serpent Mound. Recent archeological study and carbon dating suggests that Alligator Mound in Granville also dates to the Fort Ancient era, rather than the assumed Hopewell era. It is believed that neither the Serpent or Alligator Mounds are burial locations, but rather served as ceremonial effigy sites.

A number of pre-Columbian cultures in North America were collectively termed "Mound Builders", but the term has no formal meaning. It does not refer to a specific people or archaeological culture, but refers to the characteristic mound earthworks which indigenous peoples erected for an extended period of more than 5,000 years. The "Mound Builder" cultures span the period of roughly 3500 BCE to the 16th century CE, including the Archaic period, Woodland period, and Mississippian period. Geographically, the cultures were present in the region of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River Valley, and the Mississippi River Valley and its tributary waters.

Petroforms, also known as boulder outlines or boulder mosaics, are human-made shapes and patterns made by lining up large rocks on the open ground, often on quite level areas. Petroforms in North America were originally made by various Native American and First Nation tribes, who used various terms to describe them. Petroforms can also include a rock cairn or inukshuk, an upright monolith slab, a medicine wheel, a fire pit, a desert kite, sculpted boulders, or simply rocks lined up or stacked for various reasons. Old World petroforms include the Carnac stones and many other megalithic monuments.

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically higher elevation on any surface. Artificial mounds have been created for a variety of reasons throughout history, including habitation, ceremonial, burial (tumulus), and commemorative purposes.

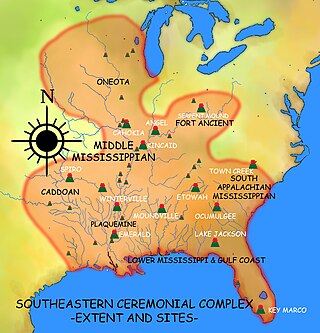

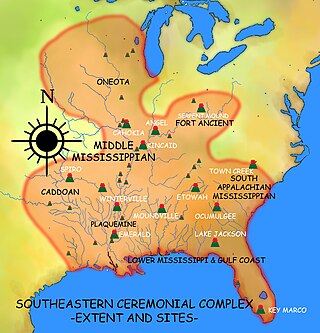

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex formerly Southern Cult, Southern Death Cult or Buzzard Cult), a.k.a. S.E.C.C., is the name given by modern scholars to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture. It coincided with their adoption of maize agriculture and chiefdom-level complex social organization from 1200 to 1650 CE.

Spiro Mounds is an archaeological site located in present-day eastern Oklahoma that remains from an indigenous Indian culture that was part of the major northern Caddoan Mississippian culture. The 80-acre site is located within a floodplain on the southern side of the Arkansas River. The modern town of Spiro developed approximately seven miles to the south.

An effigy mound is a raised pile of earth built in the shape of a stylized animal, symbol, religious figure, human, or other figure. The Effigy Moundbuilder culture is primarily associated with the years 550–1200 CE during the Late Woodland Period, although radiocarbon dating has placed the origin of certain mounds as far back as 320 BCE.

In archaeology, earthworks are artificial changes in land level, typically made from piles of artificially placed or sculpted rocks and soil. Earthworks can themselves be archaeological features, or they can show features beneath the surface.

The Alligator Effigy Mound is an effigy mound in Granville, Ohio, United States. The mound is believed to have been built between AD 800 and 1200 by people of the Fort Ancient culture. The mound was likely a ceremonial site, as it was not used for burials.

Rock Eagle Effigy Mound is an archaeological site in Putnam County, Georgia, U.S. estimated to have been constructed c. 1000 BC to AD 1000. The earthwork was built up of thousands of pieces of quartzite laid in the mounded shape of a large bird. Although it is most often referred to as an eagle, scholars do not know exactly what type of bird the original builders intended to portray. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) because of its significance. The University of Georgia administers the site. It uses much of the adjoining land for a 4-H camp, with cottages and other buildings, and day and residential environmental education.

Coso Rock Art District is a rock art site containing over 100,000 Petroglyphs by Paleo-Indians and/or Native Americans. The district is located near the towns of China Lake and Ridgecrest, California. Big and Little Petroglyph Canyons were declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964. In 2001, they were incorporated into this larger National Historic Landmark District. There are several other distinct canyons in the Coso Rock Art District besides the Big and Little Petroglyph Canyons. Also known as Little Petroglyph Canyon and Sand Tanks, Renegade Canyon is but one of several major canyons in the Coso Range, each hosting thousands of petroglyphs. The majority of the Coso Range images fall into one of six categories: bighorn sheep, entopic images, anthropomorphic or human-like figures, other animals, weapons & tools, and "medicine bag" images. Scholars have proposed a few potential interpretations of this rock art. The most prevalent of these interpretations is that they could have been used for rituals associated with hunting.

The Thunderbird Archaeological District, near Limeton, Virginia, is an archaeological district described as consisting of "three sites—Thunderbird Site, the Fifty Site, and the Fifty Bog—which provide a stratified cultural sequence spanning Paleo-Indian cultures through the end of Early Archaic times with scattered evidence of later occupation."

The Prehistory of West Virginia spans ancient times until the arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century. Hunters ventured into West Virginia's mountain valleys and made temporary camp villages since the Archaic period in the Americas. Many ancient human-made earthen mounds from various mound builder cultures survive, especially in the areas of Moundsville, South Charleston, and Romney. The artifacts uncovered in these areas give evidence of a village society with a tribal trade system culture that included limited cold worked copper. As of 2009, over 12,500 archaeological sites have been documented in West Virginia.

American Indian Rock Art in Minnesota MPS is a Multiple Property Submission (MPS) of the eligibility of many rock art properties for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. The listing is to protect and preserve Native American petroglyphs, pictographs and petroform rock art sites in the present day U.S. state of Minnesota.

Prehistory of Ohio provides an overview of the activities that occurred prior to Ohio's recorded history. The ancient hunters, Paleo-Indians, descended from humans that crossed the Bering Strait. There is evidence of Paleo-Indians in Ohio, who were hunter-gatherers that ranged widely over land to hunt large game. For instance, mastodon bones were found at the Burning Tree Mastodon site that showed that it had been butchered. Clovis points have been found that indicate interaction with other groups and hunted large game. The Paleo Crossing site and Nobles Pond site provide evidence that groups interacted with one another. The Paleo-Indian's diet included fish, small game, and nuts and berries that gathered. They lived in simple shelters made of wood and bark or hides. Canoes were created by digging out trees with granite axes.

Jack Hranicky is a Registered Professional Archaeologist (RPA). During his forty-year career his scholarship has focused on the Paleo-Indian period and, in particular, stone tools and rock art. He has published more than 200 scholarly papers and 32 books, including a two-volume, 800-page survey of the material culture of Virginia. He is the webmaster of www.bipoints.com, which is a site on American early prehistory.