Bursa is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the Marmara Region, Bursa is one of the industrial centers of the country. Most of Turkey's automotive production takes place in Bursa. As of 2019, the Metropolitan Province was home to 3,056,120 inhabitants, 2,161,990 of whom lived in the 3 city urban districts plus Gürsu and Kestel.

Mehmed I, also known as Mehmed Çelebi or Kirişçi, was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1413 to 1421. Son of Sultan Bayezid I and his concubine Devlet Hatun, he fought with his brothers over control of the Ottoman realm in the Ottoman Interregnum (1402–1413). Starting from the province of Rûm he managed to bring first Anatolia and then the European territories (Rumelia) under his control, reuniting the Ottoman state by 1413, and ruling it until his death in 1421. Called "The Restorer," he reestablished central authority in Anatolia, and he expanded the Ottoman presence in Europe by the conquest of Wallachia in 1415. Venice destroyed his fleet off Gallipoli in 1416 as the Ottomans lost a naval war.

Edirne, historically known as Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated 7 km (4.3 mi) from the Greek and 20 km (12 mi) from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second capital city of the Ottoman Empire from 1369 to 1453, before Constantinople became its capital.

Sultanzade Gazi Husrev-beg was an Ottoman Bosnian sanjak-bey (governor) of the Sanjak of Bosnia in 1521–1525, 1526–1534, and 1536–1541. He was known for his successful conquests and campaigns to further Ottoman expansion into Croatia and Hungary. However, his most important legacy was major contribution to the improvement of the structural development of Sarajevo and its urban area. He ordered and financed construction of many important buildings there, and with his will bequeathed all his wealth into endowment for the construction and long-term support of religious and educational facilities and institutions, such as the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, and the Gazi Husrev-begova Medresa complex with a Gazi Husrev-beg Library, also known as Kuršumlija.

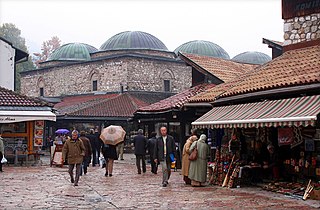

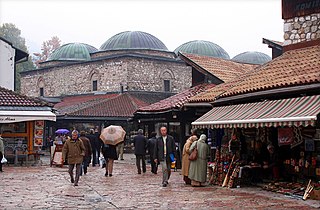

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque is a mosque in the city of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Built in the 16th century, it is the largest historical mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina and one of the most representative Ottoman structures in the Balkans. Having been Sarajevo's central mosque since the days of its construction, today it also serves as the main congregational mosque of the Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is located in the Baščaršija neighborhood in the Stari Grad municipality and, being one of the main architectural monuments in the town, is regularly visited by tourists.

Fatih is a municipality and district of Istanbul Province, Turkey. Its area is 15 km2, and its population is 368,227 (2022). It is home to almost all of the provincial authorities but not the courthouse. It encompasses the historical peninsula, coinciding with old Constantinople. In 2009, the district of Eminönü, which had been a separate municipality located at the tip of the peninsula, was once again remerged into Fatih because of its small population. Fatih is bordered by the Golden Horn to the north and the Sea of Marmara to the south, while the Western border is demarked by the Theodosian wall and the east by the Bosphorus Strait.

Türbe refers to a Muslim mausoleum, tomb or grave often in the Turkish-speaking areas and for the mausolea of Ottoman sultans, nobles and notables. A typical türbe is located in the grounds of a mosque or complex, often endowed by the deceased. However, some are more closely integrated into surrounding buildings.

Baščaršija is Sarajevo's old bazaar and the historical and cultural center of the city. Baščaršija was built in the 15th century when Isa-Beg Ishaković founded the city.

Following the proclamation of the Republic, Turkish museums developed considerably, mainly due to the importance Atatürk had attached to the research and exhibition of artifacts of Anatolia. When the Republic of Turkey was proclaimed, there were only the İstanbul Archaeology Museum called the "Asar-ı Atika Müzesi", the Istanbul Military Museum housed in the St. Irene Church, the Islamic Museum in the Suleymaniye Complex in Istanbul and the smaller museums of the Ottoman Empire Museum in a few large cities of Anatolia.

Köse Mihal accompanied Osman I in his ascent to power as a bey and founder of the Ottoman Empire. He is considered to be the first significant Byzantine renegade and convert to Islam to enter Ottoman service.

Musa Çelebi was an Ottoman prince and a co-ruler of the empire for three years during the Ottoman Interregnum.

Süleyman Çelebi was an Ottoman prince and a co-ruler of the Ottoman Empire for several years during the Ottoman Interregnum. There is a tradition of western origin, according to which Suleiman the Magnificent was "Suleiman II", but that tradition has been based on an erroneous assumption that Süleyman Çelebi was to be recognised as a legitimate sultan.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Bursa, Turkey.

Turkey–Yugoslavia relations were historical foreign relations between Turkey and now broken up Yugoslavia.

Classical Ottoman architecture is a period in Ottoman architecture generally including the 16th and 17th centuries. The period is most strongly associated with the works of Mimar Sinan, who was Chief Court Architect under three sultans between 1538 and 1588. The start of the period also coincided with the long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, which is recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.

Early Ottoman architecture corresponds to the period of Ottoman architecture roughly up to the 15th century. This article covers the history of Ottoman architecture up to the end of Bayezid II's reign, prior to the advent of what is generally considered "classical" Ottoman architecture in the 16th century. Early Ottoman architecture was a continuation of earlier Seljuk and Beylik architecture while also incorporating local Byzantine influences. The new styles took shape in the capital cities of Bursa and Edirne as well as in other important early Ottoman cities such as Iznik. Three main types of structures predominated in this early period: single-domed mosques, "T-plan" buildings, and multi-domed buildings. Religious buildings were often part of larger charitable complexes (külliyes) that included other structures such as madrasas, hammams, tombs, and commercial establishments.

Brusa bezistan with its 6 roof domes it is one of the historic buildings in Sarajevo's Baščaršija from the time of the Ottoman period in the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has a rectangular base and has four entrances on all four sides, and connects the craft streets Kundurdžiluk, Veliki and Mali Čurčiluk with Abadžiluk and the Baščaršija. It was built by order of the Grand Vizier Rustem-pasha Opuković in 1551. Bezistan was named after the Turkish city of Bursa, from which silk was brought to Bezistan and sold. Unlike Gazi Husrev-beg's bezistan, where groceries were originally sold, Brusa bezistan sold household items and small furniture in addition to silk. Today it is one of the museums in the city, designated as the National monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Commission to preserve national monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and houses one of the departments of Museum of Sarajevo.

Gazi Husrev-beg's bezistan is one of the preserved bezistan in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, from the Ottoman period in the history of the country. Built in 1555 in Baščaršija, bezistan still serves its purpose - trade.

Molla Hüsrev or Mullā Khusraw was a 15th-century Ottoman scholar and mufti.