Related Research Articles

Flagellation, flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on an unwilling subject as a punishment; however, it can also be submitted to willingly and even done by oneself in sadomasochistic or religious contexts.

In law, provocation is when a person is considered to have committed a criminal act partly because of a preceding set of events that might cause a reasonable individual to lose self control. This makes them less morally culpable than if the act was premeditated (pre-planned) and done out of pure malice. It "affects the quality of the actor's state of mind as an indicator of moral blameworthiness."

In criminal law, diminished responsibility is a potential defense by excuse by which defendants argue that although they broke the law, they should not be held fully criminally liable for doing so, as their mental functions were "diminished" or impaired.

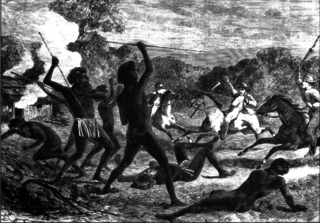

The Myall Creek massacre was the killing of at least twenty-eight unarmed Indigenous Australians by twelve colonists on 10 June 1838 at the Myall Creek near the Gwydir River, in northern New South Wales. After two trials, seven of the twelve colonists were found guilty of murder and hanged, a verdict which sparked extreme controversy within New South Wales settler society. One—the leader and free settler John Fleming—evaded arrest and was never tried. Four were never retried following the not guilty verdict of the first trial. Nevertheless, the prosecutions, the only successful one conducted against Australian settlers accused of massacring Aboriginals, have been described more as war crimes trials than a standard murder prosecution, as they occurred during the Australian frontier wars.

Capital murder refers to a category of murder in some parts of the US for which the perpetrator is eligible for the death penalty. In its original sense, capital murder was a statutory offence of aggravated murder in Great Britain, Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland, which was later adopted as a legal provision to define certain forms of aggravated murder in the United States. Some jurisdictions that provide for death as a possible punishment for murder, such as California, do not have a specific statute creating or defining a crime known as capital murder; instead, death is one of the possible sentences for certain kinds of murder. In these cases, "capital murder" is not a phrase used in the legal system but may still be used by others such as the media.

The County Court of Victoria is the intermediate court in the Australian state of Victoria. It is equivalent to district courts in the other states.

Revel Ronald Cooper was an Indigenous Australian artist. He was a prominent member of a Noongar art movement that emerged among children living at Carrolup Native Settlement during the late 1940s and early 1950s.

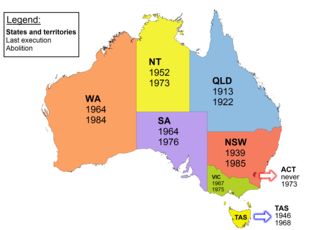

Capital punishment in Australia was a form of punishment in Australia that has been abolished in all jurisdictions. Queensland abolished the death penalty in 1922. Tasmania did the same in 1968. The Commonwealth abolished the death penalty in 1973, with application also in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. Victoria did so in 1975, South Australia in 1976, and Western Australia in 1984. New South Wales abolished the death penalty for murder in 1955, and for all crimes in 1985. In 2010, the Commonwealth Parliament passed legislation prohibiting the re-establishment of capital punishment by any state or territory. Australian law prohibits the extradition or deportation of a prisoner to another jurisdiction if they could be sentenced to death for any crime.

The Children's Court of Victoria is a statutory court created in Victoria, Australia. The court deals with criminal offences alleged to be committed by children aged between 10 and 17 and with proceedings concerning children under the age of 17 relating to the care and protection of children.

This is a timeline of Aboriginal history of Western Australia.

William John O'Meally was an Australian criminal, notorious as the last man to be flogged in Victoria.

The 2011 Helmand Province killing was the manslaughter of a wounded Taliban insurgent by Alexander Blackman, which occurred on 15 September 2011. Three Royal Marines, known during their trial as Marines A, B, and C, were anonymously tried by court martial. On 8 November 2013, Marines B and C were acquitted, but Blackman was initially found guilty of murder of the Afghan insurgent, in contravention of section 42 of the Armed Forces Act 2006. This made him the first British soldier to be convicted of a battlefield murder whilst serving abroad since the Second World War.

Lockier Clere Burges, also known as L. C. Burges junior was prominent and controversial in Western Australia as an entrepreneur, explorer and author.

John Henry Church was an Australian pastoralist and politician who was a Nationalist member of the Legislative Assembly of Western Australia from 1932 to 1933, representing the seat of Roebourne.

The Djaru people are an Aboriginal Australian people of the southern Kimberley region of Western Australia.

Athelstan Braxton Hicks was a coroner in London and Surrey for two decades at the end of the 19th century. He was given the nickname "The Children's Coroner" for his conscientiousness in investigating the suspicious deaths of children, and especially baby farming and the dangers of child life insurance. He would later publish a study on infanticide.

Myall Creek Massacre and Memorial Site is the heritage-listed site of and memorial for the victims of the Myall Creek massacre at Bingara Delungra Road, Myall Creek, Gwydir Shire, New South Wales, Australia. The memorial, which was unveiled in 2000, was added to the Australian National Heritage List on 7 June 2008 and the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 12 November 2010.

Myall Creek is a locality split between the local government areas of Inverell Shire and the Gwydir Shire in New South Wales, Australia. In the 2016 census, Myall Creek had a population of 38 people.

In May 1920, white European settler Langley Hawkins discovered money and documents were missing from his house in Kiambu County in the British East Africa Protectorate. He summoned a Black African policeman from nearby Ruiru and the pair proceeded to beat and torture three of Hawkins' black male employees and a pregnant black woman to extract information relating to the theft. One of the employees, Mucheru, died during the torture and the woman later miscarried.

In June 1923, British settler Jasper Abraham was tried for the murder of African labourer Kitosh in the Kenya Colony. Kitosh had died after a flogging administered by Abraham and his employees at a farm near the town of Molo, Kenya. The jury, which was all-white and composed of Abraham's acquaintances, found him guilty of a lesser charge of "grievous hurt" and he was sentenced to two years' imprisonment.

References

- 1 2 "Bendhu Native Case. Shocking Details. Summary of Evidence at Inquest". The Pilbara Goldfield News. 1 October 1897. p. 2.

- 1 2 Barrington, Robin (2015). Who was "Big George"? An exploration and critique of Aboriginalist discourse within historical photographic and written texts. Curtin University. p. 90. OCLC 1033937307.

- ↑ "The Bendhu Case. Anderson Found Guilty of Manslaughter. Sentenced to Penal Servitude for Life". The West Australian. 22 December 1897. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Barrington, Robin (16 December 2015). "Unravelling the Yamaji imaginings of Alexander Morton and Daisy Bates". Aboriginal History. 39: 27–61 (p. 37). doi: 10.22459/ah.39.2015.02 . ISSN 0314-8769.

- 1 2 Finnane, Mark (2015). "A politics of prosecution: the conviction of Wonnerwerry and the exoneration of Jerry Durack in Western Australia 1898". Law in Context. 33 (1): 60–73.

- 1 2 "The Bendhu Atrocities. Opinions of the Eastern Australian Press". The West Australian. 5 January 1898. p. 3.

- ↑ "The Bendhu Case". Western Mail. 28 January 1898. p. 20.